Lawrence A. Rainey

Lawrence Andrew Rainey (March 2, 1923 – November 8, 2002) was a native Mississippian who was elected Sheriff of Neshoba County, Mississippi during the 1960s. He gained notoriety for allegedly being involved in the June 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Rainey was a member of Mississippi's White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan

Lawrence A. Rainey | |

|---|---|

Sheriff Lawrence Rainey Mugshot; Late 1964. | |

| Born | March 2, 1923 |

| Died | November 8, 2002 (aged 79) |

| Cause of death | Throat and Tongue Cancer |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Sheriff |

| Conviction(s) | None, Not Guilty |

| Criminal charge | Conspiring to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate. |

Alan Parker's Mississippi Burning is a fictionalized version of the Freedom Summer Murders. It was released in 1988 and starred Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe.

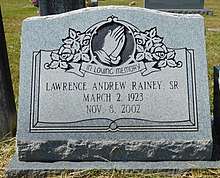

Rainey died of cancer in 2002 and is buried next to his family in Kemper County, Mississippi.

Background

Rainey grew up in Kemper and Neshoba County, Mississippi. His parents were John and Bessie Rainey. Rainey had a younger brother who died at a young age. Rainey's education stopped at the 8th grade which was not unusual in the early 20th century. His father was a farmer, and they were likely poor sharecroppers during the Great Depression. He worked as a mechanic before starting in a career in law enforcement.

Rainey started his career as a police officer working in Philadelphia, Mississippi. In October 1959, he shot and killed a black motorist who was getting out of his car, but he was not prosecuted. Rainey had a reputation as a brutal law enforcement officer.

He successfully ran for the office of Sheriff in 1963 and has been quoted as positioning himself as "the man who can cope with situations that might arise", a veiled reference to the racial tension in the area at the time. One of his deputies was Cecil Price.

Freedom Summer Murders

In the afternoon of June 21, 1964, Chaney, Goodman, & Schwerner arrived at Longdale to inspect the burned out church in Neshoba County. They left Longdale around 3 p.m. They were to be in Meridian by 4 p.m. that day. The fastest route to Meridian was through Philadelphia. At the fork of Beacon & Main Street their station wagon sustained a flat tire. It is possible that a shot was fired at the station wagon's tire. Rainey's home was near the Beacon & Main Street fork. Deputy Cecil Price soon arrived and escorted them to the county jail. Price released the trio as soon as the longest day of the year became night which was about 10 p.m. The three were last seen heading south along Highway 19 toward Meridian.

On the day of the murders, Rainey was visiting his wife at the hospital in Meridian. He allegedly left Meridian about 6 p.m. for Collinsville where he had supper with relatives. Rainey visited his stepmother in Philadelphia and then went to his office to pick up some clothing. He went to his home to pick up some gowns for his wife and left the gowns with his relatives in Collinsville, where he watched television shows Bonanza and Candid Camera, then returned home. At the trial it was alleged but not proven that he had learned of the murder early the following morning and deliberately covered it up.

On July 18, 1964, Rainey unsuccessfully sued NBC, the Lamar Life Broadcasting Company, Southern Television Corporation, and Buford W. Posey for one million dollars for slander due to an interview which Posey gave to NBC during the investigation of the disappearance of the civil rights workers.

Prosecution

On January 15, 1965, Rainey and seventeen others learned that they were indicted. Because there was, at that time, no federal murder statute, they were charged with violation of the three men's civil rights. In 1967, the case went to trial in federal court and Rainey was acquitted, though six others were convicted.

Legacy

Despite his acquittal, Rainey was stigmatized by his role in the events. His law enforcement career ended in 1968 when he was not re-elected as Sheriff of Neshoba County. As a result of the trial, his wife became an alcoholic, and they divorced. She subsequently died of a brain tumor.[1]

For years after the Freedom Summer Murders, Rainey had difficulty finding stable employment; he worked as an auto mechanic and as a security guard in Kentucky and Mississippi, including a long stint as a security guard in Meridian, Mississippi. Rainey's employers included the Matty Hersee state charity hospital and the Village Fair Mall. A stint at the IGA grocery store ended abruptly after the airing of the CBS program "Attack on Terror" in 1975; bomb threats were made against the supermarket for hiring him, and they subsequently fired him.[2] His boss at McDonald's Security Guard Service was an African American, and Rainey described the firm as "better to work for than any white company".[3]

He later blamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the media for preventing him from finding and keeping jobs, and reiterated that he was not a racist:

They tried to make it that I hated the black people, and it was just because I had to shoot two, ... Anyone I mistreated in law enforcement made me do it in order of fulfilling my job and duties (…) You got trash in all colors."

— Lawrence A. Rainey, People, Since Mississippi Burned, January 9, 1989

He developed throat cancer and tongue cancer, and died in 2002 at the age of 79.

Media portrayals

Attack on Terror: The FBI vs. the Ku Klux Klan was the first fictional version of the Freedom Summer Murders. Actor Geoffrey Lewis played as Sheriff Ed Duncan, a fictionalized Lawrence Rainey.

In the 1988 film Mississippi Burning, the character of Sheriff Ray Stuckey was a fictionalized depiction of Lawrence Rainey. The part was played by Gailard Sartain.

See also

References

- "Since Mississippi Burned". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Since Mississippi Burned". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "Since Mississippi Burned". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved 2019-07-16.

External links

- Editorial about Lawrence Rainey by R. Emmett Tyrrell

- Neshoba Democrat article about the lawsuit against NBC

- Biography in the Mississippi Burning site by the University of Missouri-Kansas City

- More information on the trial from the University of Missouri-Kansas City

- Lawrence A. Rainey at Find a Grave