Lasioglossum figueresi

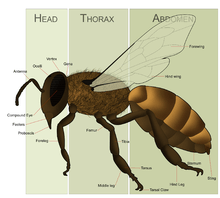

Lasioglossum figueresi, formerly known as Dialictus figueresi, is a solitary sweat bee[1] that is part of the family Halictidae of the order Hymenoptera.[2] Found in Central America, it nests in vertical earthen banks which are normally inhabited by one, though sometimes two or even three, females. Females die before their larvae hatch.[3] It was named after José Figueres Ferrer, a famous Costa Rican patriot, and studies of its behavior are now general models for social behavior studies.[4]

| Lasioglossum figueresi | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. figueresi |

| Binomial name | |

| Lasioglossum figueresi Wcislo, 1990 | |

Taxonomy and phylogeny

L. figueresi is part of the subfamily Halictinae, of the hymenopteran family Halictidae.[2] The largest, most diverse and recently diverged of the four halictid subfamilies,[5] Halictinae (sweat bees) is made up of five tribes of which L. figueresi is part of Halictini, which is made up of over 2000 species.[6] Genus Lasioglossum is informally divided into two series: the Lasioglossum series and the Hemihalictus.[7] L. figueresi belongs to the latter and is part of the subgenus Dialictus which is made up mostly of New World species.[1][8] It is most closely related to L. marginatum, L. politum,[9] and L. aeneiventre.[10]

Description and identification

L. figueresi is closely related morphologically to L. aeneiventre. Unusually large, it is described in relation to L. aeneiventre as well as other Dialictus. In general, L. figueresi differs from other bees by its wings, hair, and markings.[10]

Females

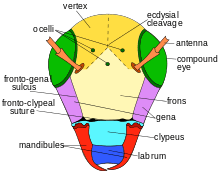

A female L. figueresi is recognized from L. aeneiventre and other Dialictus by its unique striped pattern on the sternum of its mesothorax, the pattern of punctures on its front scutum of its middle thoracic segment, its larger size, its hair, and its slightly yellow wings including the membrane, veins, and stigma. Generally larger than males, it has a metallic dark-green head and a clypeal length greater than that of its supraclypeal area, which is slightly rounded and bulges. It does not have a frontal line ridge from below the base of the antenna to about half the distance between its antennal sockets to its median ocellus, and its lateral ocelli are slightly nearer to each other than to their compound eyes. It has punctures near its eyes, on the lower half of the clypeus, sometimes on the supraclypeal area, and on the frons, while its gena is shiny and its supraclypeal area and frons have dull spaces in between. In the middle of its thorax, it has a groove that is two-thirds the length of its metallic dark-green scutum of its middle thoracic segment, with deep punctures that divide as one moves towards the head, as well as about twelve stripes on each side which almost wrap around the propodeum. Its black metasoma is shiny and mostly smooth, its brown-tinted black legs are shiny and flattened on the front surface with a well-defined rim raised above the surface of the plate at the base of the tarsus, and its sharply rounded wings have dull yellow membranes with smokey tips. Its veins and stigma are a golden-yellow-brown. It has yellowish hair on its head, abundant golden yellow hair on its mesosoma, long, plumose, and golden hair on its metanotum, metasomal terga, and metasoma, slightly yellow, short, and fine hair on its tegula, yellow-white fringed hair on the pseudopygidial area, and a dense golden band of hair on its pronotal lobe.[10]

Males

A male L. figueresi is distinct from other Dialictus by many of the female characteristics as well as those of its genitals. In comparison to a female, its compound eyes on its dark-green head converge more below and become wavy, and it has punctures on the clypeal area, vertex, and frons. Its scutum of its middle thoracic segment has a deeply grooved middle line and a parapsidal line like in the female, its clypeus is dark green-purple with dark brown antennae that are lighter underneath and a brownish black tegula, and its terga has very close punctures with a shiny terga I-IV. Compared to the females, the male's wings are clearer, its veins are nearly brown, and its yellow to golden-yellow hair is sparser. Its genitalia also differs from other Dialictus since its gonostylus is nearly equal in length to its gonocoxite with the additional shape and position of the hairs.[10]

Distribution and habitat

L. figueresi is a tropical bee that nests in the ground of highly disturbed, highly populated, and highly cultivated areas of Costa Rica's Mesenta Central. The nests are made of material that is easily accessible from their location. This region's weather consists of a dry season from late November or December until April or May and a subsequent wet season with a small period of less rain. It is found in groups of nests, similar to the American sweat bee Lasioglossum zephyrus,[11] and these groups are more numerous at higher elevations. Nests are marked by turrets made of small mud balls and are constructed during the night at the active season's beginning. A female adds to the turrets with its pygidium after bringing mud from inside the nest. When turrets are destroyed, it will only repair or replace them if the soil is soft and malleable and will not close off the entrance like some other types of bees.[3]

Nest structure

Usually found close together, the nests of L. figueresi are made up of earthen material with entrances to nests sometimes fused together. Earthen turrets, made up of small balls of mud which form a bumpy exterior and smooth interior, indicate the position of these nests, and the tunnels of these nests are almost perpendicular to the surrounding surface. Cells, coated in shiny secretions, are shortened tunnels that branch off from the main tunnel, and, once used, are normally filled up with dirt and not re-used.[3]

Colony cycle

During the lull in the wet season, from late June to early July, female L. figueresi emerge from their nests, mate, and then either establish new nests or, more rarely, re-use old nests. Heavy rains prevent much mating and foraging but some females keep extra cells open for new larvae for sporadic favorable weather during the rainy season. Nests typically contain a female and her offspring and are enlarged at the beginning of the dry season in late November and early December. Only seasonally active, females store up pollen only until mid-February and die after their first season of reproduction. During the dry season, it is more difficult to dig up the hardening soil so there is less creation of nests. Broods stay and grow in their nest.[3] By May, males and females co-exist yet don't work on the nest at this time.[1] After about 80 days, which is considerably longer than the 20 to 35 days of other halictine bees, they become young adults and leave the nest around mid-June, mating with others and starting the cycle over again.[3]

Development and reproduction

In general, female L. figueresi are mated with developed ovaries.[3] Development, however, starts with the larvae, feeding on pollen and nectar, in the nest.[1] As they grow, males and females live together. When they become adults at around 80 days, they leave the nest, mate with others, and then after preparing the next generation through the creation or re-use of nests, they die.[3]

Sexual attraction

The odors of female L. figueresi are an important stimulus for sexual attraction in males. Each female has its own unique scent. In cage experiments, male L. figueresi were more inclined towards dead females that were untreated compared to dead females that were washed in hexane, which removed their odor. The odor of females even increased the response of males to other cues. In the field, males attempted to copulate with models when paired with a female scent. These results also indicate that stimulation by sight increases with the presence of female odors. Female attractiveness is variable, and males take note of each other's preferences in choosing females. Therefore, less attractive females are less likely to mate.[12]

Mating behavior

During the characteristic lull of the rainy season, male and female L. figueresi leave their nest in order to mate. Males patrol the aggregations in an area, and when they notice a female that lands, they fly in a snake-like path towards her, pouncing on her head and causing them to fall together to the ground. There is no courtship, only copulatory vibrations that occur for various lengths of time. Additionally, males sometimes jump on other males' heads or other wasps or insects. While flying around, males are not overtly aggressive to other males. However they attempt to push off other males who are copulating with females.[12]

Learning

After continued interaction with one female, a male L. figueresi becomes less and less responsive to that female and therefore less likely to continue mating with her. This habituation shows that males learn from female odors which makes it more likely for them to mate with a greater variety of females. Additionally, males have developed the ability to learn and remember which females are responsive or nonresponsive to them, therefore decreasing the amount of time they waste on females who are nonresponsive. With their increased learning ability, they can also differentiate between receptive females and choose those who are more genetically favorable.[12]

Behavior and ecology

As solitary bees,[1] L. figueresi interact differently with the environment around them. Sometimes more than one female works on a nest, which affects the size and scope of the nest. Additionally, females have a routine that helps them become more effective at providing for their offspring.[3]

Social organization

In general, a nest contains one female L. figueresi and her offspring. In 9% to 21% of the time, two females can be found at a nest. However, there is no strong difference in size between the two females, even in comparing a mated female with an unmated female. Additionally, two-female nests contained either two mated females with developed ovarioles or one mated female with developed ovarioles and one unmated female with undeveloped ones. Having an additional female can double the amount of cells that a nest could contain, compared to other social insects which decline in efficacy as the number of individuals increases. Solitary female nests can contain up to 14 cells while two-female nests can have up to 24 cells.[3] However, the solitary nature of L. figueresi could have evolved away from eusociality. Between two unrelated females, body size was found to not be related to which bee would be more aggressive to the other, yet for bees from a reproductive time period, the female with the larger ovaries was more likely to be aggressive while the one with smaller ovaries was more likely to withdraw. Therefore, these solitary bees could still be affected by qualities of social bees as shown by their appropriate behaviors in response to other females. Additionally, females recognize bees from their own nest and are more aggressive towards those from other nests.[1]

Diel activity

Female L. figueresi begin their day around 8 or 9 AM when the temperature reaches 20–21 °C (68–70 °F). They sit at the entrance to their nest for up to 14 minutes, most likely warming up their muscles needed for flight, and then forage between 7 and 46 minutes. They can make up to 5 foraging trips a day if the weather is favorable.[3]

Interaction with other species

L. figueresi, though solitary,[1] interacts with plants and parasites. Plants provide it with pollen and nectar as food for both themselves and their larvae, while parasites invade their nests and affect their survival. As a result, these bees have evolved defenses in response to these parasites.[3]

Diet

The diet of L. figueresi consists of balls of pollen from larvae to adults. Adult females search for and consume pollen balls made from several sources such as Melampodium divaricatum, which is unique to L. figueresi and is most likely due to its abundance in their area, Croton bilbergianus, and other Asteraceae.[3] Additionally, they stock cells with both pollen and nectar for their larvae.[1]

Parasites

The main parasite of L. figueresi is the fly Phalacrotophora halictorum.[3] The parasitism occurs during the fly's courtship behavior. After copulation, female flies enter the nest of L. figueresi when the female host is not present. Male flies continue courting the females even after initial copulation and therefore follow the female into the nest, taking it over.[13] Another potential parasite is fungi which either cause or contribute to death. Solitary female nests are as parasitized as two-female nests.[3] Other potential enemies of L. figueresi are species of Conopidae, Sphecodes, and Mutillidae. Sometimes ants invade nests and destroy brood during their scavenging.[4]

Defense against parasites

L. figueresi defend their nest from parasitism primarily by guarding the nest to prevent the flies from entering, but they also create extra, empty brood cells.[3] These empty cells cause greater difficulty for parasites in finding the larvae of L. figueresi.[14]

References

- Wcislo, W. T. (1997). Social interactions and behavioral context in a largely solitary bee, Lasioglossum (Dialictus) figueresi (Hymenoptera, Halictidae), 44, 199–208. Retrieved from

- "Lasioglossum figueresi". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Wcislo, W. T., Wille, A., Orozco, E. (1993). Nesting biology of tropical solitary and social sweat bees, Lasioglossum (Dialictus) figueresi Wcislo and L. (D.) aeneiventre (Friese) (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). 40, 21–40. Retrieved from .

- Wcislo, W. T. (1991). Natural History, Learning, And Social Behavior in Solitary Sweat Bees (Hymenoptera, Halictidae). [Dissertation] Retrieved from .

- Schwarz, M. P. et al. (2007). "Changing paradigms in insect social evolution: Insights from halictine and allodapine bees". Annual Review of Entomology 52: 127–150. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.15095.

- Danforth, B. N. et al. (2008). "Phylogeny of Halictidae with emphasis on endemic African Halictinae" (PDF). Apidologie 39: 86–101. doi:10.1051/apido:2008002.

- Michener, C.D. (2000). The Bees of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. 913.

- Danforth B. N. and Wcislo W. T. (1999). "Two new and highly apomorphic species of the Lasioglossum subgenus Evylaeus (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) from Central America" (PDF). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am., 92(5), 630. doi:10.1051/apido:2008002.

- Danforth B. N., Conway L., Ji S., (2003). "Phylogeny of eusocial Lasioglossum reveals multiple losses of eusociality within a primitively eusocial clade of bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae)" Syst. Biol., 52(1), 23–36.

- Wcislo, W. T., (1990). A new species of Lasioglossum from Costa Rica (Hymenoptera: Halictidae), 63, 450–453. Retrieved from .

- Crozier, R. H.; Smith, B. H.; Crozier, Y. C. (1987-07-01). "Relatedness and population structure of the primitively eusocial bee Lasioglossum zephyrum (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) in Kansas". Evolution. 41 (4): 902–910. doi:10.2307/2408898. JSTOR 2408898. PMID 28564347.

- Wcislo, W. T., (1992). Attraction and learning in mate-finding by solitary bees, Lasioglossum (Dialictus) figueresi Wcislo and Nomia triangulifera Vachal (Hymenoptera: Halictidae). 31, 139–148. Retrieved from .

- Wcislo, W. T. (1990). Parasitic and courtship behavior of Phalacrotophora halictorum (Diptera: Phoridae) at a nesting site of Lasioglossum figueresi. Revista de Biología Tropical. 38(2A), 205–209. Abstract retrieved from .

- Tepedino, V. J., McDonald, L. L., Rothwell, R. (1979). Defense against parasitization in mud-nesting Hymenoptera: Can empty cells increase net reproductive output? 6(2), 99–104. Retrieved from .