Laptot

Laptots were African colonial troops in the service of France between 1750 and the early 1900s.

History

The term laptot probably derives from the word lappato bi in the Wolof language, referring to interpreters, intermediaries or brokers.[1] Most laptots were recruited in Senegal, especially at French outposts in Saint-Louis and Dakar, during the late 18th and 19th centuries. Laptots were closely linked with the Tirailleurs sénégalais, a military unit which enlisted soldiers from France's colonies in West Africa, founded in 1857. Unlike the tirailleurs, however, laptots served exclusively in Africa and Madagascar.[2]

The French navy hired laptots on a temporary basis, using them to guard outposts, serve aboard French naval and commercial vessels, and perform various other tasks throughout French possessions in Africa. Laptots typically signed up for two-year contracts. They were often more reliable and effective than European personnel, who were too susceptible to endemic diseases such as malaria. Many laptots joined on a voluntary basis, although others were slaves in local communities who were forced to hand over half their wages to their owners. According to historian Francois Manchuelle, pay for some laptots—particularly those who served aboard navy boats on the Senegal River—was competitive with salaries for French sailors at the time. Manchuelle contends that men of the Soninke ethnic group were attracted to laptot service by the prospects of accumulating cash with which to compete for social status in their home communities.[3]

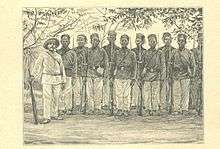

Laptots were essential not only to French administration of its West African possessions, but also to subsequent French exploration and colonial penetration of Central Africa, parts of which became French Equatorial Africa after 1910. When the Franco-Italian explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza first ventured into the Equatorial African interior in 1876, he was accompanied by 13 laptots and four local interpreters as well as three other Frenchmen. Brazza's second expedition, in 1880, also relied heavily on laptots to carry loads, deliver messages, and provide protection against hostile populations. One laptot on this expedition was Malamine Camara, who achieved some renown for his exploits while serving under Brazza's command in Congo. Camara and two other laptots manned France's first outpost on the banks of the Congo River from October 1880 until May 1882, on the future site of Brazzaville, and may have prevented France's newly acquired territory there from being taken over by Belgium.[4] Laptots provided the bulk of French manpower needs in its Equatorial African colonies until well into the 20th century, when more personnel began to be recruited locally.[5]

References

- James F. Searing. (1993) West African Slavery and Atlantic Commerce: The Senegal River Valley, 1700-1860 (New York: Cambridge University Press), p 77.

- Philip D. Curtin. (1975) Economic Change in Precolonial Africa: Senegambia in the Era of the Slave Trade. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- François Manchuelle. (1997) Willing Migrants: Soninke Labor Diasporas, 1848-1960. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- Charles de Chavannes. (1935) Avec Brazza : Souvenirs de la Mission de l’Ouest Africaine (mars 1883 – janvier 1886). Paris: Plon.

- Cathérine Coquery-Vidrovitch. (1969) Brazza et la Prise de Possession du Congo : La Mission de l’Ouest Africain, 1883-1885. Paris: Mouton & Co.