Landsmanshaft

A landsmanshaft (also landsmanschaft; plural: landsmanshaftn) is a mutual aid society, benefit society, or hometown society of Jewish immigrants from the same European town or region.

History

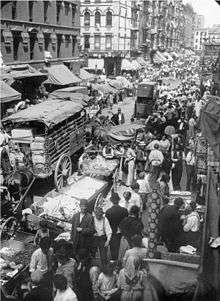

The Landsmanshaft organizations aided immigrants' transitions from Europe to America by providing social structure and support to those who arrived in the United States without the family networks and practical skills that had sustained them in Europe. Toward the end of the 19th and in the beginning of the 20th centuries, they provided immigrants help in learning English, finding a place to live and work, locating family and friends, and an introduction to participating in a democracy, through their own meetings and procedures such as voting on officers, holding debates on community issues, and paying dues to support the society. Through the first half of the 20th century, meetings were often conducted and minutes recorded in Yiddish, which was the language that all members could understand.[1] As Jewish immigration declined, most landsmanshaft functions faded into the background, but the organizations nevertheless continued as a way of maintaining ties to life in Europe as well as providing a form of life insurance, disability and unemployment insurance, and subsidized burial.

Members paid dues on a regular basis, and if they lost their jobs, became too sick to work, or died, the society paid the member or their family a benefit to keep them afloat during that time. When the funds were not needed to support members, landsmanshaftn frequently invested the money in funds that supported the Jewish community in others ways, such as Israel Bonds.[2] Most landsmanshaftn were based in New York City, where the majority of Jews settled and conditions were conducive to sustaining these types of organizations, though they sometimes relocated as the membership migrated to the suburbs.

Types

There were different types of landsmanshaftn, including Jewish burial societies known as chevra kadisha, societies associated with a particular synagogue or social movement, and "ladies auxiliary" societies for women.[3] (Landsmanshaftn frequently admitted only men as members, with the understanding that their wives and children were covered by their membership and received equivalent benefits, or had a ladies' auxiliary group for women). The Workmen's Circle/Arbeter Ring is a mutual aid society with more than 200 branches, but because it is not based on geography or members' hometowns, is not strictly a landsmanshaft even though it largely functions as one.

In 1938, a federal Works Progress Administration project identified 2,468 landsmanshaftn in New York City, where the overwhelming number in the United States were located.[4] The number of landsmanshaftn began to decline in the 1950s and 1960s as their members died and were not replaced by the next generation of their members' children. The vast majority became defunct, though some societies continue to meet regularly into the 21st century, and operate scores of burial plots in cemeteries in the New York metropolitan area.[5]

Decline

Over time, landsmanshaftn lost members as they aged and died, and many became defunct. The next generation felt less need of a connection to Europe, relied on the national programs of the New Deal if they needed financial support during difficult times, and because they were not immigrants, didn't need landsmanshaftn to socialize or meet others. When officers were not replaced, it sometimes resulted in difficulties for the relatives of members who died, because the officers were required to issue burial permits to the cemeteries in which their plots were located. The state of New York, particularly the Department of Insurance, stepped in to take over these functions for some groups. Many records of defunct landsmanshaftn eventually made their way from the New York State Department of Insurance to the archives of YIVO.

References

- Soyer, Daniel (1997). Jewish Immigrant Associations and American Identity in New York, 1880-1939 - Jewish Landsmanshaftn in American Culture. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3032-0.

- Weisser, Michael R., A Brotherhood of Memory: Jewish Landsmanshaftn in the New World, Cornell University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8014-9676-4, p. 14-23.

- Weisser, Michael R., A Brotherhood of Memory: Jewish Landsmanshaftn in the New World, Cornell University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8014-9676-4, p. 13-14.

- Rontach, Isaac (ed.) (1938). Di idishe landsmanshaftn fun Nyu York (The Jewish Landsmanschaften of New York). New York: I.L. Peretz Yiddish Writers’ Union.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Vitello, Paul (August 2, 2009). "With Demise of Jewish Burial Societies, Resting Places Are in Turmoil". New York Times. p. A15. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

See also

External links

- JewishGen Landsmanschaft - Immigrant Benevolent Organizations

- "New York Landsmanshaftn and Other Jewish Organizations". Jewish Genealogical Society, New York

Bibliography

- Schwartz, Rosaline and Susan Milamed, From Alexandrovsk to Zyrardow: A Guide to YIVO's Landsmanshaftn Archive, New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 1986.

- Soyer, Daniel, Jewish immigrant associations and American identity in New York, 1880-1939, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2001.

- Weisser, Michael R., A Brotherhood of Memory: Jewish Landsmanshaftn in the New World, Cornell University Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8014-9676-4.