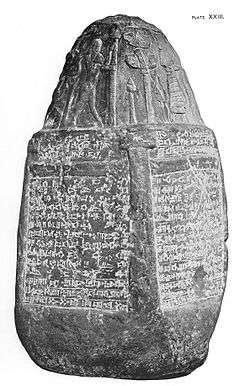

Land grant to Ḫasardu kudurru

The land grant to Ḫasardu kudurru, is a four-sided limestone narû, or memorial stele, from the late 2nd millennium BC Mesopotamia recording the gift of 144 hectares of land on the bank of the Royal Canal in the Bīt-Pir’i-Amurru region of the Diyala valley by Kassite monarch Meli-Šipak (ca. 1186–1172 BC) to an official or sukkal mu’irri, by the name of Ḫa-SAR-du (reading uncertain). It is titled, “O Adad, the hero, bestow irrigation ditches of abundance here!"[1] and is notable for the light it sheds on middle Babylonian officialdom.

The stele

The object was excavated by Hormuzd Rassam during his 1881–82 excavations in Sippar on behalf of the British Museum. It was recovered, along with two other entitlement stelae, from a room in the temple of Šamaš[1] and given the museum reference BM 90829.

Deities invoked

Thirteen gods are invoked by name together with "all the gods whose names are portrayed on this narû." These are represented by eighteen icons arranged around the conical top.

The god Marduk is pictured twice, once by a kusarikku holding a spade, and once with a marru or tasseled spade in front of the kusarikku. Ea may be represented both by the south wind and a ram-headed crook.[2] Šuqamuna and Šumalia, the Kassite deities associated with the investiture of kings are portrayed by a bird on a perch. Several of the symbols are widely attested icons of their gods such as the lunar disc for Sîn, solar disc for Šamaš, the lightning-fork for Adad, the lamp for Nusku, the leaping dog for Gula, the mace with twin lion-heads for Nergal, the eagle-headed mace for Ninurta, the eight-pointed star for Ištar, and the coiled snake for Ištaran.[3]

Cast of characters

The principal parties to the transaction were the king and a Kassite military official:

- Meli-Šipak, šar kiššati, "king of the world" (the donor)

- Ḫa-SAR-du, son of Sumû, sukkal mu'erru, messenger? of the commander[4] (the beneficiary)

The title sukkal mu'erru suggests his rȏle is as a representative or liaison officer at the royal court on behalf of the military commander, or mu'erru.[5]

The officials conducting the transfer:

- Ibni-Marduk, "son of Arad-Ea," šādid eqli, the surveyor

- Šamaš-muballiṭ, ḫazannu, mayor of Bīt-Pir’i-Amurru or possibly its (chief) magistrate[6]

- Bau-aḫu-iddina, ṭupšar šakin māti, the scribe to the "ruler of the land," probably a provincial governor

- Itti-Marduk-balāṭu, ša rēš šarri (lúSAG LUGAL), the king's representative, a servant

The witnesses to the transaction:

- Iddina-Marduk, šakkanak māt tāmtim bīt-Mallaḫi, a governor of a province in the Sealand, southern Mesopotamia

- Rizi ... ni (a Kassite), kartappu (lúKA.DIB), the chariot commander[4]

- Libur-zanin-Ekur, ša rēši (lúSAG), a court official

- Lūṣa-ana-nūri-Marduk, sukkallu ṣīru, grand vizier or first-rank courtier

- Iqīša-Bau, "son of Arad-Ea," role unknown

- Šamaš-šum-lišir, son of Atta-iluma, šakkanak Agade. mayor of the city of Agade

- Kidin-Marduk, (lúMEŠ.GAL), high official?

The term ša rēši designated a royal eunuch in the Assyrian court but there is no evidence of a similar fate for a court official in middle Babylonia.[7] Furthermore, Kidin-Marduk (not the witness on this kudurru), an official with this title is pictured bearded having inherited the position from his father, and later bequeathing it to his son, on a cylinder seal of the reign of Burna-Buriaš II.[8] It is significant that both the military positions are occupied by Kassites.

Principal publications

- C. W. Belser (1894). "Babylonische Kudurru-Inschriften". In F. Delitzsch, Paul Haupt (ed.). Beiträge zur Assyriologie, II. J. C. Hinrichs. pp. 165–169. “Grenzstein” no. 101

- F. E. Peiser (1896). "Babylonische Urkunden aus der dritten Dynastie". In K. B. Schrader (ed.). Keilinschriftliche Bibliothek, IV. Reuther & Reichard. pp. 56–60.

- L. W. King (1912). Babylonian Boundary Stones and Memorial-Tablets in the British Museum. British Museum. pp. 19–23, pls. XXIII–XXX.

- Ursula Seidl (1989). Die Babylonischen Kudurru-Reliefs: Symbole Mesopotamischer Gottheiten. Academic Press Fribourg. 24, 221 no. 12, for the detail 168f no. XLIII

References

- Eleanor Robson (2008). Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History. Princeton University Press. pp. 167, 169.

- F. A. M. Wiggerman (2007). "The Four Winds and the Origins of Pazuzu". In Claus Wilcke (ed.). Das Geistige Erfassen Der Welt Im Alten Orient: Sprache, Religion, Kultur Und Gesellschaft. Eisenbrauns. p. 154.

- Tallay Ornan (2005). The Triumph of the Symbol: Pictorial Representation of Deities in Mesopotamia and the Biblical Image Ban. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 45–52.

- L. Sassmannshausen (2001). Betträge zur verwaltung und Gesellschaft Babyloniens in der Kassitenzeit. Philipp von Zabern. pp. 55, 59.

- mu'irru CAD m 2, p. 179.

- ḫazannu CAD ḫ, p. 164.

- J. A. Brinkman (1968). A Political History of post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158-722 B.C. (AnOr. 43). Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. pp. 309–311.

- L. R. Siddal (2007). "A re-examination of the title ŠA REŠI in the Neo-Assyrian period". In Joseph Azize, N. Weeks (ed.). Gilgamesh and the World of Assyria: Proceedings of the Conference Held at the Mandelbaum House, The University of Sydney, 21-23 July 2004. Peeters Publishers. pp. 225–226.