Laguna de los Cerros

Laguna de los Cerros is a little-excavated Olmec and Classical era archaeological site, located in the vicinity of Corral Nuevo, within the municipality of Acayucan, in the Mexican state of Veracruz, in the southern foothills of the Tuxtla Mountains, some 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of the Laguna Catemaco.

| Olmec Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

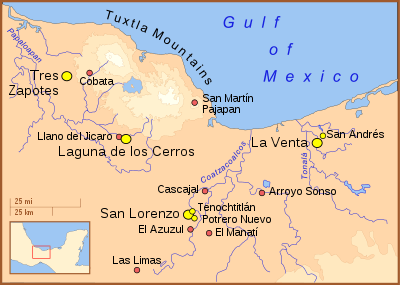

Laguna de los Cerros and other sites in the Olmec heartland | ||

| Name: | Laguna de los Cerros | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | Corral Nuevo, Acayucan, Veracruz | |

| Region | Mesoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 18°6′N 95°7′W | |

| Culture | Olmec | |

| Language | ||

| Chronology | 1200 BCE to 900 CE | |

| Period | Mesoamerican Classical | |

| Apogee | 250 to 900 CE | |

| INAH Web Page | Non existent | |

With Tres Zapotes, San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, and La Venta, Laguna de los Cerros is considered one of the four major Olmec centers.[1]

Laguna de los Cerros ("lake of the hills") was so named because of the nearly 100 mounds dotting the landscape. The basic architectural pattern consists of long parallel mounds flanking large rectangular plazas. Conical mounds mark the plaza ends. Larger mounds, formerly raised residential platforms, are associated with the thinner parallel mounds.[2]

It has been confirmed that the site was not occupied during the postclassical period.[2]

Most of the mounds date from the Classical era, roughly 250 CE through 900 CE.[3]

This region, and the early Olmec people, presumably was the penetration point for commerce between the Mexico highlands and Tuxtepec routes.[4]

Background

The first major culture in Veracruz was the Olmecs. The Olmecs settled in the Coatzacoalcos River region and it became the center of Olmec culture. The main ceremonial center here was San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. Other major centers in the region include Tres Zapotes in the city of Veracruz and La Venta in Tabasco. The culture reached its height about 2,600 years ago, with its best-known artistic expression being the colossal stone heads.[5] These ceremonial sites were the most complex of that early time period. For this reason, many anthropologists consider the Olmec civilization to be the mother civilization of the many Mesoamerican cultures that followed it.[6] By 300 BCE, this culture was eclipsed by other emerging cultures in Mesoamerica.[7]

History

Due to its location in a pass between the river valleys to the south and the northwest, and its proximity to basalt[8] sources in the volcanic Tuxtla Mountains to the north, Laguna de los Cerros was occupied over an uncharacteristically long period – perhaps close to 2,000 years, from Olmec times until the Classic era.

Laguna de los Cerros was likely settled between 1400 - 1200 BCE and by 1200 BCE it had become a regional center, covering as much as 150 hectares (370 acres). By 1000 BCE, it had nearly doubled in size with 47 smaller sites within a 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) radius.[9] One of these satellite sites was Llano del Jícaro, largely a workshop for monumental architecture due to the nearby basalt flows. Monuments carved from Llano del Jícaro basalt can be found not only at Laguna de los Cerros, but also the large Olmec center of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán some 60 kilometres (37 mi) to the southeast. It is thought likely that Llano del Jícaro was controlled by San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, either directly or through control of Laguna de los Cerros.[10]

Llano del Jícaro was abandoned sometime after 1000 BCE and Laguna de los Cerros itself shows a significant decline at that time. The cause of this decline is not known – perhaps a shift in the course of the San Juan River[11] – but it does roughly coincide with the decline and abandonment of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, which is often attributed to environmental difficulties.

Laguna de los Cerros was briefly investigated by Alfonso Medellin Zenil in 1960 and by Ann Cyphers in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The site

Unlike the other three major Olmec sites, no colossal heads have been found at Laguna de los Cerros, although roughly two dozen other Formative period monuments have been found.

Important samples of ceramic, basalt stone and other materials were found in various excavations of the site during 1997 and 1998. The ceramic material classification was made on the macroscopic characteristics of the paste and surface. The comparative study of ceramics prior to the late classical period with pre-established sequences is ongoing.[2]

The ceramic found correspond to various shapes, the main types are as follows :[2]

- ACHIOTE ORANGE. A medium texture mainly intense orange paste

- ANONA LIGHT GRAY, typical light gray color.

- CACHIMBA BLACK, the paste color fluctuates from medium to dark gray, and black, occasionally with the presence of brown hues.

- CAMPAMENTO FINE ORANGE, designates a group with fine orange pastes.

- CEIBA COARSE CREAM,[12] is a cream color that may show light orange shades.

- MANGAL YELLOW, distinctive paste yellow color

- NANCHE COARSE ORANGE, the color fluctuates from orange to a reddish yellow.

- YUAL FINE CREAM, at macroscopic level it seems to be identical to Yual Fine Cream,[13] similar to Campamento Fine Orange and Zapote Fine Orange to Grey.

- ZAPOTE FINE GRAY, name used from Coe and Diehl’s classification (1980:I:218), the paste is similar to Zapote Fine Orange to Gray.

Human burials were also found during excavations, some had ceramic and other offerings.[2]

Also found many articles of different types and shapes, included are some 2,635 articles ranging from vessels, polishers, dishes, tablets, strikers, mortars, metates, basalt flakes, spheres, rings, sharpeners, etc.[2]

The accuracy of the cultural development is based on the ceramic sequences used to generate it. The chronology, together with the prevailing poor state of preservation of the ceramics involved, affect the way in which such development may be understood. Chronologies in neighboring areas have been refined (for instance Pool 1990, 1995; Stark 1989, 1995, 2001; Daneels 2002), and they represent a major comparative support for the present study.[2]

References

- Pool, or Diehl. Cyphers, however, finds that "recent investigations do not support the notion that [Laguna de los Cerros] was a large Olmec center".

- Cyphers, Ann (March 2004). "Laguna de los Cerros, A Terminal Classic Period Capital in the Southern Mexican Gulf Coast". FAMSI. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- Diehl, p. 46-47.

- "Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México, Acayucan Veracruz" [Encyclopedia of the municipalities of Mexico, Acayucan, Veracruz] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2007-05-23. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- "Historia" [History]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- Malmstrom, Vincent "Cycles of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican Civilization" 1997 University of Texas Press, p22 http://www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/

- Schmal, John P. (2004). "The History of Veracruz". Houston Institute for Culture. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- Medellín 1960; Gillespie 1994, 2000

- Pool, p. 129. Dates are in chronological, and not radiocarbon, years which vary considerably during this period).

- Pool, p. 131. Another alternative is that Laguna de los Cerros controlled Llano del Jícaro, and San Lorenzo traded for the finished basalt monuments and stelae.

- Pool, p. 155.

- The name was maintained due to the similarities with Coarse Ceiba paste and forms, defined by Coe and Diehl (1980:I:221)

- As defined by Coe and Diehl (1980:I:220)

Bibliography

- Bove, Frederick, 1978 Laguna de los Cerros, an Olmec central place. Journal of New World Archaeology 2 (3):1-56.

- Coe, Michael D. and Richard A. Diehl 1980. In the land of the Olmec. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Cyphers, Ann, 1997. Informe del Proyecto Arqueológico San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán: Temporada 1997. Informe presentado al Consejo de Arqueología del INAH, México.

- Cyphers, Ann and Joshua Borstein n.d. Laguna de los Cerros. Mecanoescrito.

- Daneels, Annick, 2002, El patrón de asentamiento del periodo Clásico en la cuenca baja del río Cotaxtla, centro de Veracruz. Tesis de doctorado, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Gillespie, Susan D. (1994). "Llano del Jícaro: An Olmec Monument Workshop" (PDF). Ancient Mesoamerica. pp. 231–242. doi:10.1017/S095653610000119X.

- Malmstrom, Vincent H. 1997 Cycles of the Sun, Mysteries of the Moon: The Calendar in Mesoamerican Civilization. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX (also accessible at www.dartmouth.edu/~izapa/)

- Medellín, Alfonso, 1960 Monolitos inéditos olmecas. La Palabra y el Hombre 16:75-97.

- Pool, Christopher, 1990 Ceramic production, resource procurement, and exchange at Matacapan, Veracruz, Mexico. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tulane University, New Orleans.

- Stark, Barbara L. 1989 Patarata pottery: Classic period ceramics of the south-central coast, Veracruz, Mexico. Anthropological Papers No. 51. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Stark, Barbara, ed. 2001 Classic period Mixtequilla, Veracruz, Mexico, Diachronic inferences from residencial investigations. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies Monograph 12. Albany: The University at Albany.

- Stark, Barbara L. and Philip J. Arnold, 1997 Introduction to the archaeology of the Gulf lowlands. In Olmec to Aztec, Settlement patterns in the ancient Gulf lowlands, B.L. Stark and P.J. Arnold, eds., pp. 3–32. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Symonds, Stacey, 1995 Settlement distribution and the development of cultural complexity in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage, Veracruz, Mexico: An archaeological survey at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. Ph.D. Dissertation, Vanderbilt University.

- Symonds, Stacey, Ann Cyphers and Roberto Lunagómez, 2002 Asentamiento prehispánico en San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Coe, Michael D. (2002); Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs London: Thames and Hudson.

- Cyphers, Ann (2003) "Laguna de los Cerros: A Terminal Classic Period Capital in the Southern Mexican Gulf Coast", Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., accessed February 2007.

- Diehl, Richard A. (2004) The Olmecs: America's First Civilization, Thames & Hudson, London.

- Grove, David C. (2000) "Laguna de los Cerros (Veracruz, Mexico)", in Archaeology of Ancient Mexico & Central America: an Encyclopedia; Thames and Hudson, London.

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3.

External links

- Acayucan Municipality Official Web Page (in Spanish)