Labidochirus splendescens

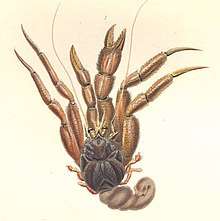

Labidochirus splendescens, commonly known as the splendid hermit crab, is a species of hermit crab found in the northeastern Pacific Ocean off the coast of North America. It is more heavily calcified and inhabits smaller mollusc shells than most hermit crabs.

| Labidochirus splendescens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. splendescens |

| Binomial name | |

| Labidochirus splendescens (Owen, 1839) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Taxonomy

This species was first collected during the exploratory expedition by HMS Blossom (1825–1827) off the Kamchatka Peninsula, in eastern Siberia. The specimens collected were sent to London where this hermit crab was first described in 1839 by the English naturalist Richard Owen, curator of the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons.[3] He named it Pagurus splendescens,[2] becoming Labidochirus splendescens in the seventies when the subgenus Labidochirus, of which it was the type, was raised to generic status.[4]

Description

Labidochirus splendescens can grow to a carapace width of about 2.8 cm (1.1 in). The carapace is armed with dorsal spines and is more heavily calcified than is the case in most hermit crabs. The walking legs are relatively long and the crab "wears" a mollusc shell that appears to be too small. The crab's body and legs are brown or pinkish and have a reddish iridescent sheen.[5]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

This hermit crab is native to the northeastern Pacific Ocean and Arctic Ocean, its range extending as far south as Puget Sound in Washington state. It occurs from the shallow subtidal zone down to about 412 m (1,350 ft); it frequents open sandy or muddy places.[5]

Association with hydroids

Because L. splendescens has a well-calcified carapace, the gastropod mollusc shell which it inhabits is only needed to provide protection for its soft abdomen. However, the crab almost exclusively chooses shells in which to live on which stinging colonial hydroids in the genus Hydractinia are growing; these are likely to provide extra protection to the hermit crab, but it is unknown whether the association is mutually beneficial.[6] The hydroids are lightly calcified and may grow so thickly as to extend or even partially replace the mollusc shell as the hermit crab's shelter; X-raying such a "shell" sometimes shows gastropod-like spiral growth of hydractinians extending from the original shell, while little remains of the gastropod shell itself.[5]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labidochirus splendescens. |

- McLaughlin, Patsy (2009). Lemaitre R, McLaughlin P (eds.). "Labidochirus splendescens (Owen, 1839)". World Paguroidea & Lomisoidea database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Owen, Richard (1839). "Crustacea". In Beechey, F.W. (ed.). The Zoology of Captain Beechey's Voyage. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 77–97, 81. BHL page 27208189.

- Garth, John S.; Wicksten, Mary K. (1993). "Studies on decapod crustaceans of the Pacific coast of the United States and Canada". In Truesdale, Frank (ed.). History of Carcinology. Crustacean Issues. 8. CRC Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-90-5410-137-6.

- Laughlin, Patsy A. (1974). "The hermit crabs (Crustacea, Decapoda, Paguridae) of northwestern North America". Zoologische Verhandelingen. 130: 1–396, 342.

- Cowles, Dave (2005). "Labidochirus splendescens (Owen, 1839)". Invertebrates of the Salish Sea. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Thiel, Martin; Watling, Les (2015). Lifestyles and Feeding Biology. Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-19-979702-8.