Laacher See

Laacher See (German pronunciation: [ˈlaːxɐ ˈzeː]) or Lake Laach (in English) is a volcanic caldera lake with a diameter of 2 km (1.2 mi) in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, about 24 km (15 mi) northwest of Koblenz and 37 km (23 mi) south of Bonn, and is closest to the town of Andernach situated 8 km (5.0 mi) to the east on the river Rhine. It is in the Eifel mountain range, and is part of the East Eifel volcanic field within the larger Vulkan Eifel. The lake was formed by a Plinian eruption approximately 12,900 years BP with a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 6, on the same scale as the Pinatubo eruption of 1991.[1][2][3][4]

| Laacher See | |

|---|---|

View of the caldera volcano | |

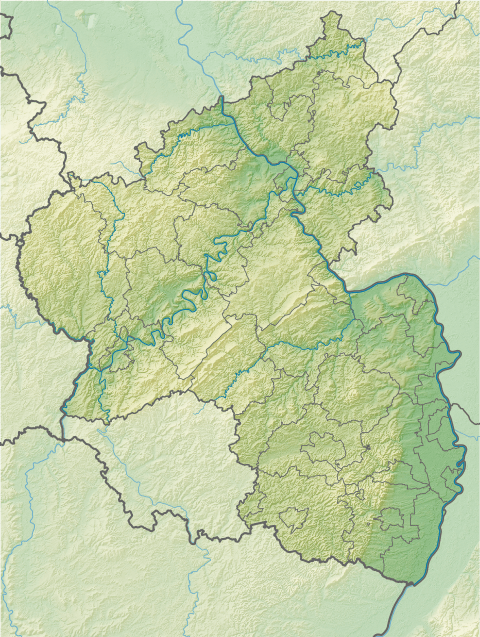

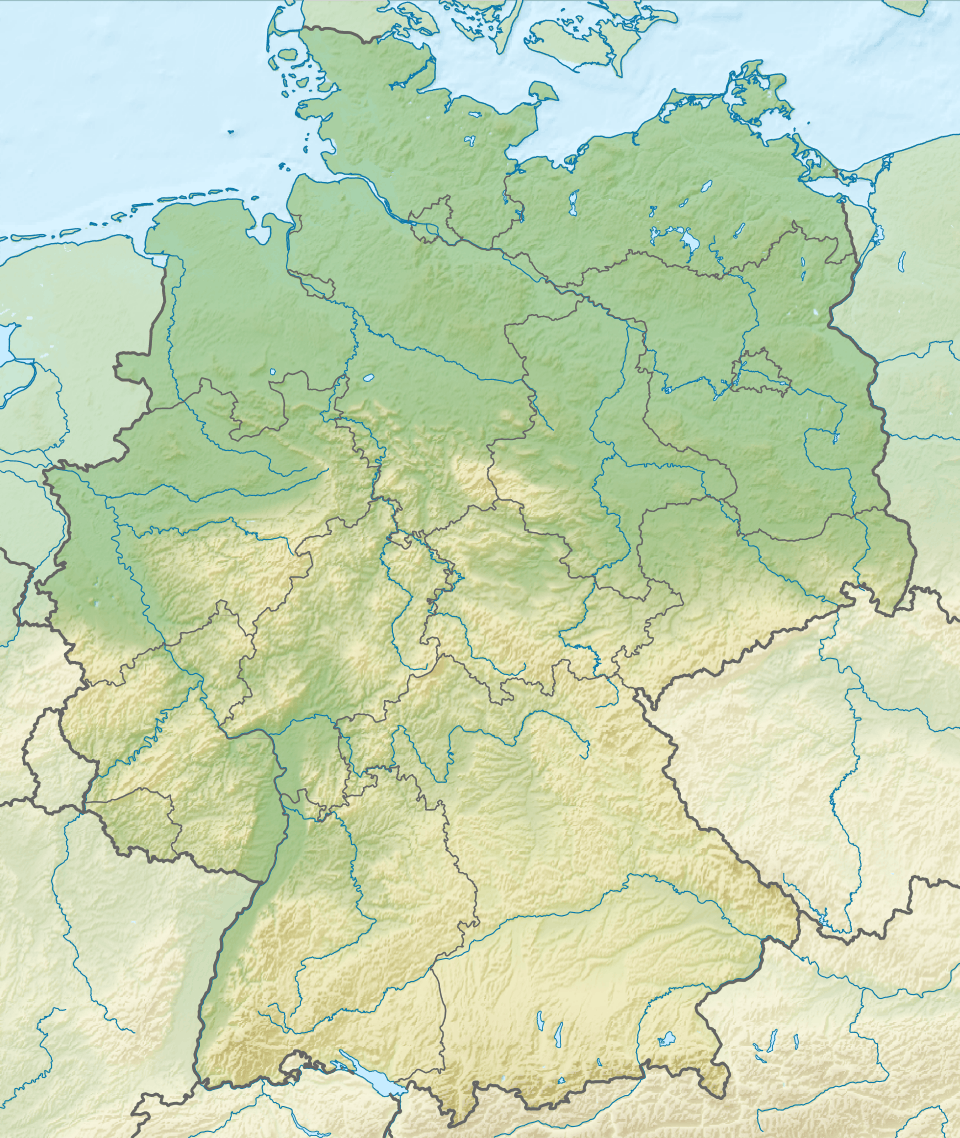

Laacher See Location in Germany  Laacher See Laacher See (Germany) | |

| Location | Ahrweiler, Rhineland-Palatinate |

| Coordinates | 50°25′N 7°16′E |

| Type | crater lake, caldera lake |

| Primary outflows | Fulbert-Stollen (canal) |

| Basin countries | Germany |

| Surface area | 3.3 km2 (1.3 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | 53 m (174 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 275 m (902 ft) |

Description

The lake is oval in shape, and surrounded by high banks. The lava was quarried for millstones from the Roman period until the introduction of iron rollers for grinding corn.[5]

On the western side lies the Benedictine monastery of Maria Laach Abbey (Abbatia Lacensis), founded in 1093 by Henry II of Laach of the House of Luxembourg, first Count Palatine of the Rhine, who had his castle opposite to the monastery above the eastern lakeside.

The lake has no natural outlet, but is drained by a tunnel dug before 1170 and rebuilt several times since. It is named after Abbot Fulbert, abbot from 1152–1177, who is believed to have built it.

The eruption

Volcanism in Germany can be traced back for millions of years, due to the collision between the African and Eurasian plates, but it has been concentrated in bursts associated with the loading and unloading of ice during glacial advances and retreats. The initial blasts of Laacher See, which took place in late spring or early summer, flattened trees up to four kilometres away. The magma opened a route to the surface which erupted for about ten hours, with the plume probably reaching a height of 35 kilometres. Activity continued for several weeks or months, with pyroclastic currents which covered valleys up to ten kilometres away with sticky tephra. Near the crater deposits are over fifty metres, and even five kilometres away they are still ten metres thick. All plants and animals for a distance of about sixty kilometres to the northeast and forty kilometres to the southeast must have been exterminated.[6] An estimated 6 km3 (1.4 cu mi) of magma erupted,[7] producing around 16 km3 (3.8 cu mi) of tephra.[8] This 'huge' Plinian eruption thus had a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 6.

Tephra deposits from the eruption dammed the Rhine, creating a 140 km2 (50 sq mi) lake. When the dam broke, an outburst flood swept downstream, leaving deposits as far away as Bonn.[7] The fallout has been identified in an area of more than 300,000 square kilometres, stretching from central France to northern Italy, and from southern Sweden to Poland, making it an invaluable tool for chronological correlation of archaeological and palaeoenvironmental layers across the area.[9]

Aftermath of the eruption

The wider effects of the eruption were limited, amounting to several years of cold summers and up to two decades of environmental disruption in Germany. However, the lives of the local population, known as the Federmesser culture, were disrupted. Before the eruption, they were a sparsely distributed people who subsisted by foraging and hunting, using both spears and bows and arrows. According to archaeologist Felix Riede, after the eruption the area most affected by the fallout, the Thuringian Basin occupied by the Federmesser, appears to have been largely depopulated, whereas populations in southwest Germany and France increased. Two new cultures, the Bromme of southern Scandinavia and the Perstunian of northeast Europe emerged. These cultures had a lower level of toolmaking skills than the Federmesser, particularly the Bromme who appear to have lost the bow and arrow technology. In Riede's view the decline was a result from the disruption caused by the Laacher See volcano.[10]

See also

References

- Oppenheimer, Clive (2011). Eruptions that Shook the World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-521-64112-8.

- de Klerk, Pim; et al. (2008). "Environmental impact of the Laacher See eruption at a large distance from the volcano: Integrated palaeoecological studies from Vorpommern (NE Germany)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 270 (1–2): 196–214. Bibcode:2008PPP...270..196D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.09.013.

- Bogaard, Paul van den (1995). "40Ar/39Ar ages of sanidine phenocrysts from Laacher See Tephra (12,900 yr BP): Chronostratigraphic and petrological significance". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 133 (1–2): 163–174. Bibcode:1995E&PSL.133..163V. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(95)00066-L.

- "Geo-Education and Geopark Implementation in the Vulkaneifel European Geopark/Vulkanland Eifel National Geopark". The Geological Society of America. 2011.

- Hull, Edward (1892). Volcanoes: Past and Present (2010 ed.). Echo Library. pp. 73–74. ISBN 9781406868180.

- Oppenheimer, pp. 216-218

- Schmincke, Hans-Ulrich; Park, Cornelia; Harms, Eduard (1999). "Evolution and environmental impacts of the eruption of Laacher See Volcano (Germany) 12,900 a BP". Quaternary International. 61 (1): 61–72. Bibcode:1999QuInt..61...61S. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(99)00017-8.

- P.v.d. Bogaard, H.-U. Schmincke, A. Freundt and C. Park (1989). Evolution of Complex Plinian Eruptions: the Late Quarternary (sic) Laacher See Case History, "Thera and the Aegean World III", Volume Two: "Earth Sciences", Proceedings of the Third International Congress, Santorini, Greece, 3–9 September 1989. pp. 463–485.

- Oppenheimer, p. 218.

- Oppenheimer, pp. 217-222

Further reading

- Ginibre, Catherine; Wörner, Gerhard; Kronz, Andreas (2004). "Structure and Dynamics of the Laacher See Magma Chamber (Eifel, Germany) from Major and Trace Element Zoning in Sanidine: a Cathodoluminescence and Electron Microprobe Study". Journal of Petrology. 45 (11): 2197–2223. Bibcode:2004JPet...45.2197G. doi:10.1093/petrology/egh053.

- Park, Cornelia; Schmincke, Hans-Ulrich (1997). "Lake Formation and Catastrophic Dam Burst during the Late Pleistocene Laacher See Eruption (Germany)". Naturwissenschaften. 84 (12): 521–525. Bibcode:1997NW.....84..521P. doi:10.1007/s001140050438.

- Riede, Felix (2008). "The Laacher See-eruption (12,920 BP) and material culture change at the end of the Allerød in Northern Europe". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (3): 591–599. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.05.007.

- Hensch, Martin; Dahm, Torsten; Ritter, Joachim; Heimann, Sebastian; Schmidt, Bernd; Stange, Stefan; Lehmann, Klaus (2019). "Deep low-frequency earthquakes reveal ongoing magmatic recharge beneath Laacher See Volcano (Eifel, Germany)". Geophysical Journal International. 216 (3): 2025–2036. Bibcode:2019GeoJI.216.2025H. doi:10.1093/gji/ggy532.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Laach. |

- Continuous event display of the 10 most recent registered seismic activities measured from the Laacher See

- Nixdorf, B.; et al. (2004), "Laacher See", Dokumentation von Zustand und Entwicklung der wichtigsten Seen Deutschlands (in German), Berlin: Umweltbundesamt, p. 28

- Apokalypse im Rheintal (Cornelia Park und Hans-Ulrich Schmincke)