La Quemada

La Quemada is an archeological site, also known (according to different versions) as Chicomóztoc.[1][2] It is located in the Villanueva Municipality, in the state of Zacatecas, about 56 km south of the city of Zacatecas on Fed 54 Zacatecas–Guadalajara, in Mexico.

La Quemada | |

Salón de las Columnas | |

| Location | Villanueva Municipality, Zacatecas, Mexico |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Periods | 300 to 1200 AD |

| Cultures | Chalchihuites |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia |

| Website | Zona Arqueológica La Quemada |

History

Given the distance between La Quemada and the centre of Mesoamerica, this archeological zone has been subject of different interpretations on the part of historians and archeologists, who have attempted to associate it with different cultures.

It is supposed that this place could be the legendary Chicomostoc, a Caxcan site, a Teotihuacán fortress, a Purépecha centre, a fort against Chichimeca intruders, a Toltec trading post, or simply consequence of independent development and a city of all the native groups established north of the Río Grande de Santiago.

In 1615, Fray Juan de Torquemada identified La Quemada as one of the places visited by the Aztecs during their migration from the north to the Mexico central plateau, and where older people and children were left behind. Francisco Javier Clavijero, in 1780, associated this site with Chicomoztoc, where the Aztecs remained for nine years during their voyage to Anahuac. This speculation originated the belief La Quemada is the mythical place called "The Seven Caves". Archeological investigations since the 1980s determined that La Quemada developed between 300 and 1200 AD (Classical and early Postclassical periods) and that it was contemporaneous of the Chalchihuites culture, characterized from the first century of our era, by intense mining activity. La Quemada, Las Ventanas[3] El Ixtepete, major settlements in the "Altos de Jalisco", and northern Guanajuato, formed a trade network linked to Teotihuacán (350-700 AD), that extended from northern Zacatecas to the Valley of Mexico. It is possible that links established by Teotihuacán were with local rulers of ceremonial centers, of the mentioned network, or through alliances with regional intermediaries, or by small Teotihuacán merchants groups, living in these centers, that ensured the various products flow, such as minerals, salt, shells, quills, obsidian, and peyote, among others.

Between 700 and 1100 AD, La Quemada did not participate as a network member, but as the dominant trade location at the regional level, it began to compete with other neighbouring sites. It was during this time that the site acquired a defensive character, evidence of which is the construction, on the north flank of the site, of a wall approximately four metres high by four metres wide, as well as the elimination of two stairways in the complex with the intention of restricting internal circulation.

From the evidence of fire in several parts of the site, a violent decline of the settlement is inferred. It is this apparent destruction by fire which gives the site its name of la (ciudad) quemada, "the burnt city".

The site

La Quemada is made up of numerous different size masonry platforms built onto the hill, these were foundations for structures built over them. On the south and southeastern sides is a high concentration of ceremonial constructions, some of which are complexes made up of sunken patio platforms and altar-pyramid, a typical Mesoamerican architectonic attribute.

On the west side is a series of platforms or terraces, apparently more residential structures than ceremonial. All architectonic elements of La Quemada were constructed with rhyolite (volcanic effusive rock of the granite family) slabs, extracted from the hill located northeast of the Votive Pyramid.

To build the structures and join the slabs a clay and vegetal fiber mortar was used, as it degrades and erodes in time, it caused wall deterioration. Over the masonry walls several clay stucco layers were applied, currently only a few samples of original finishing remain.

Studies made to date, provide basis to determine that the monumental complex was constructed at different times. It is known that the structures built were constructed over previous constructions, which were covered by later constructive stages.

If the total elements of this site are considered, from the extensive roads and the numerous smaller sites linked to La Quemada, this is a singular archaeological site in the context of mesoamerican sites.

Structures

The archaeological zone is divided into three complexes: the "Ciudadela" with a wall that surrounds the north side of the site (800m long, 4m wide and 4m high); the Palace located in the central part of the hill and the Temple located in the south end.[4]

Salón de las Columnas

Columns Hall. This 41 by 32 metre enclosure, probably reached a height of more than five metres before the fire that caused its destruction. In their interior eleven columns supported the roof. Until now its specific function is not known. Although works made in the 1950s indicate a ceremonial use possibly related to human sacrifice.[5]

Calzada Mayor

Main Avenue. This esplanade extends about 400 metres from the plaza in front of the Columns Hall, where many smaller dimension roads initiate that cross the Malpaso Valley. In order to construct this road, as well as the majority of other roads, side walls were built of stone slabs and stone; later the area in between the walls was covered with stone slabs and a pavement made of clay and pebbles. If the proportion of this element with respect to other dimensions of the site is considered, its size is remarkable. In addition, there are vestiges to two altars at the main entrance end. Recent studies confirm the existence of more than 170 kilometers of roads that cross the valley and interconnect several other smaller archaeological sites.[5]

Juego de Pelota

Ballgame Court. This structure, of mesoamerican features, was constructed on an enormous platform that extends from the north of the Votive Pyramid throughout the access stairway at the south slope of the court. It measures 70 by 15 metres and it displays the characteristic letter "I" shape; the side walls are as wide as those of the Columns Hall (2.70 meters) and assumed a height of between three and five meters.[5] As is the case in almost all archaeological sites in Mexico, this site has had vandalism.

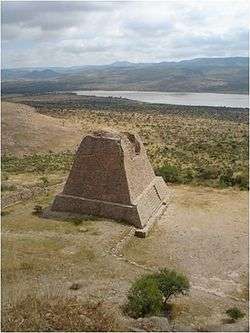

Pirámide Votiva

Votive Pyramid. This structure, more than 10 metres high, is highlighted by the angle of its slopes. During Corona Nuñez works, in 1995, slope vestiges with remains of a stairway were found, that ascended the south side of the pyramid. With time the middle and top parts crumbled to the ground, where they can be seen at the present time. Originally, the stairway reached the top of the pyramid where a room or temple constructed with perishable materials apparently existed.[5]

Escalinata

Stairway. At about 30 metres west of the Votive Pyramid this stairway was discovered, was used as main access to the top levels of the site. It was constructed in two stages; the first, that approximately reached the middle of the height now observed, apparently it was round shape, and can be associated with shapes of now missing structures; the second, built over the former and with greater height, it reached the walkway on the second level, evidence shows ties with a two ramp stairway that ascended to the third level. At a point in time the main stairway was cancelled, by defence reasons by means of the retaining wall, limiting access.[5]

Other platforms

In the third level sector of the site, on the west side of the hill, are numerous platforms or terraces that, according to recent investigation works are residential areas; to date 25 structures constructed towards 650 AD, have been identified.[5]

Muralla

This wall (Muralla is the protective perimeter wall) is emphasized, by its dimensions (four metres high by three metres thick) as well as by its location on edges of the cliffs surrounding the north and northeast parts of the site. Apparently this structure was constructed towards the end of the occupation of La Quemada and, perhaps, it represents one of the best indicators of the problems faced by city residents as well as their perseverance to remain there.[5]

Ciudadela

Located at the highest part of the site,[4] several buildings have been identified, possibly used for ceremonial and defensive purposes.

Site museum

Located in the archaeological zone, its architectonic design was conceived such that it integrates to the surrounding landscape and the archaeological site by the use of material characteristic of the buildings constructed in the site (stone slabs, stucco and finishing). This museum offers a panorama of the region archaeological evolution through diverse informative elements, a site scale model and descriptive videos of the main prehispanic settlements in Zacatecas: Loma San Gabriel, Chalchihuites and of course La Quemada.[7]

Notes

- Chicomoztoc is the name of the mythical place of origin for Aztecs, Mexicas, Tepanecs, Acolhuas and other Nahuatl (or Nahua) speaking peoples from Mesoamerica, in the central region during the Postclassical period. Other versions locate this mythical place in Culhuacan (Valley of Mexico), Cerro Culiacán (Guanajuato), etc.

- "El sitio arqueológico de La Quemada". rincones de mi tierra. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- Archaeological site located in the Cañón de Juchipila, Zacatecas

- Espejel, Ricardo (2003–2005). "Chicomoztoc - La Quemada, Zacatecas. Field trip" (in Spanish). Source: INAH Site mini-guide: espejel.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- Jiménez Betts, Peter. "Zona Arqueológica La Quemada, Pagina Web INAH" [La Quemada archaeological site, INAH Web page]. INAH (in Spanish). Mexico. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- The text editor. "There are no references to this structure at La Quemada archaeological site, INAH Web page". INAH. Mexico.

- "La Quemada, Zona Arqueológica" [Archaeological Site, La Quemada] (in Spanish). travelbymexico.com. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

References

- Chicomoztoc - La Quemada, Zacatecas. Ricardo Espejel Cruz, 2003–2005.