Kucha

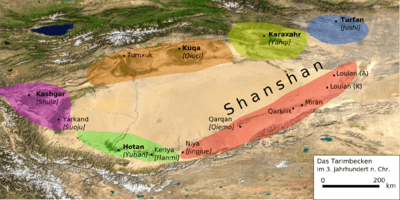

Kucha or Kuche (also: Kuçar, Kuchar; Uyghur: كۇچار , Кучар; Chinese: 龜茲; pinyin: Qiūcí; Sanskrit: Kucina),[1] was an ancient Buddhist kingdom located on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in the Tarim Basin and south of the Muzat River.

Kucha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 111 AD–648 AD | |||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||

| Demonym(s) | Kuchean | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | Before 111 AD | ||||||

| 648 AD | |||||||

| Population | |||||||

• 111 AD | 81,317 | ||||||

| Currency | Kucha coinage | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||

The area lies in present-day Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China; Kuqa town is the county seat of that prefecture's Kuqa County. Its population was given as 74,632 in 1990.

Etymology

The history of toponyms for modern Kucha remain somewhat problematic,[2] although it is clear that Kucha, Kuchar (in Turkic languages) and Kuché (modern Chinese),[3] correspond to the Kushan of Indic scripts from late antiquity.

While Chinese transcriptions of the Han or the Tang infer that Küchï was the original form of the name, Guzan (or Küsan), is attested in the Old Tibetan Annals (s.v.), dating from 687 AD.[4] Uighur and Chinese transcriptions from the period of the Mongol Empire support the forms Küsän/Güsän and Kuxian/Quxian respectively, [5] rather than Küshän or Kushan. Another, cognate Chinese transliteration is Ku-sien.[3]

Transcriptions of the name Kushan in Indic scripts from late antiquity include the spelling Guṣân, and are apparently reflected in at least one Khotanese-Tibetan transcription.[6]

The forms Kūsān and Kūs are attested in the 16th century work Tarikh-i-Rashidi.[7] Both names, as well as Kos, Kucha, Kujar etc., were used for modern Kucha.[3]

Chinese names of Kucha – 曲先; 屈支 屈茨; 丘慈 丘玆 邱慈; 俱支曩; 归兹; 拘夷; 苦叉 and; 姑藏 – have been romanized as Quxian, Quici, Chiu-tzu, Kiu-che, Kuei-tzu, Guizi, Juyi, Kucha and Guzang. While 龜玆 has sometimes been romanized as Qiuzi (or Wade-Giles: Ch'iu-tzu), this is generally regarded as incorrect; the second character is more properly represented as ci (Wade-Giles: tz'u).[8]

History

Kingdom

According to the Book of Han (completed in 111 AD), Kucha was the largest of the "Thirty-six Kingdoms of the Western Regions", with a population of 81,317, including 21,076 persons able to bear arms.[9]

For a long time, Kucha was the most populous oasis in the Tarim Basin. As a Central Asian metropolis, it was part of the Silk Road economy, and was in contact with the rest of Central Asia, including Sogdiana and Bactria, and thus also with the cultures of South Asia, Iran, and coastal areas of China.[10] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited Kucha and in the 630s described Kucha at some length, and the following are excerpts from his descriptions of Kucha:

The soil is suitable for rice and grain...it produces grapes, pomegranates and numerous species of plums, pears, peaches, and almonds...The ground is rich in minerals-gold, copper, iron, and lead and tin. The air is soft, and the manners of the people honest. The style of writing is Indian, with some differences. They excel other countries in their skill in playing on the lute and pipe. They clothe themselves with ornamental garments of silk and embroidery.... There are about one hundred convents in this country, with five thousand and more disciples. These belong to the Little Vehicle of the school of the Sarvastivadas. Their doctrine and their rules of discipline are like those of India, and those who read them use the same originals....About 40 li to the north of this desert city there are two convents close together on the slope of a mountain...Outside the western gate of the chief city, on the right and left side of the road, there are erect figures of Buddha, about 90 feet high.[11]

_-_Kucha_area_-_Scott_Semans.jpg)

A specific style of music developed within the region and "Kuchean" music gained popularity as it spread along the trade lines of the Silk Road. Lively scenes of Kuchean music and dancing can be found in the Kizil Caves and are described in the writings of Xuanzang."[T]he fair ladies and benefactresses of Kizil and Kumtura in their tight-waisted bodices and voluminous skirts recall--notwithstanding the Buddhic theme--that at all the halting places along the Silk Road, in all the rich caravan towns of the Tarim, Kucha was renowned as a city of pleasures, and that as far as China men talked of its musicians, its dancing girls, and its courtesans."[12] Kuchean music was very popular in Tang China, particularly the lute, which became known in Chinese as the pipa.[13] For example, within the collection of the Guimet Museum, two Tang female musician figures represent the two prevailing traditions: one plays a Kuchean pipa and the other plays a Chinese jiegu (an Indian-style drum).[14] The "music of Kucha" was transmitted from China to Japan, along with other early medieval music, during the same period, and is preserved there, somewhat transformed, as gagaku or Japanese court music.[15]

Conquest by Tang

Following its conquest by the Tang dynasty in the 7th century, during Emperor Taizong's campaign against the Western Regions, the city of Kucha was regarded by Han Chinese as one of the Four Garrisons of Anxi: the "Pacified West",[16] or even its capital. During periods of Tibetan domination it was usually at least semi-independent. It fell under Uyghur domination and became an important center of the later Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho after the Kyrgyz destruction of the Uyghur steppe empire in 840.[17]

The extensive ruins of the ancient capital and temple of Subashi (Chinese Qiuci), which was abandoned in the 13th century, lie 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of modern Kucha.

Modern Kucha

Francis Younghusband, who passed through the oasis in 1887 on his journey from Beijing to India, described the district as "probably" having some 60,000 inhabitants. The modern Chinese town was about 700 square yards (590 m2) with a 25 feet (7.6 m) high wall, with no bastions or protection to the gateways, but a ditch about 20 feet (6.1 m) deep around it. It was filled with houses and "a few bad shops". The "Turk houses" ran right up to the edge of the ditch and there were remains of an old city to the south-east of the Chinese one, but most of the shops and houses were outside of it. About 800 yards (730 m) north of the Chinese city were barracks for 500 soldiers out of a garrison he estimated to total about 1,500 men, who were armed with old Enfield rifles "with the Tower mark."[18]

Modern Kucha is part of Kuqa County, Xinjiang. It is divided into the new city, which includes the People's Square and transportation center, and the old city, where the Friday market and vestiges of the past city wall and cemetery are located. Along with agriculture, the city also manufactures cement, carpets and other household necessities in its local factories.

Archaeological investigations

There are several significant archaeological sites in the region which were investigated by the third (1905–1907, led by Albert Grünwedel) and fourth (1913–1914, led by Albert von Le Coq) German Turfan expeditions.[19][20] Those in the immediate vicinity include the cave site of Achik-Ilek and Subashi.

Kucha and Buddhism

It was an important Buddhist center from Antiquity until the late Middle Ages. Buddhism was introduced to Kucha before the end of the 1st century, however it was not until the 4th century that the kingdom became a major center of Buddhism,[21] primarily the Sarvastivada, but eventually also Mahayana Buddhism during the Uighur period. In this respect it differed from Khotan, a Mahayana-dominated kingdom on the southern side of the desert.

According to the Book of Jin, during the third century there were nearly one thousand Buddhist stupas and temples in Kucha. At this time, Kuchanese monks began to travel to China. The fourth century saw yet further growth for Buddhism within the kingdom. The palace was said to resemble a Buddhist monastery, displaying carved stone Buddhas, and monasteries around the city were numerous.

Kucha is well known as the home of the great fifth-century translator monk Kumārajīva (344-413).

Monks

Po-Yen

A monk from the royal family known as Po-Yen travelled to the Chinese capital, Luoyang, from 256-260. He translated six Buddhist texts into Chinese in 258 at China's famous White Horse Temple, including the Infinite Life Sutra, an important sutra in Pure Land Buddhism.

Po-Śrīmitra

Po-Śrīmitra was another Kuchean monk who traveled to China from 307-312 and translated three Buddhist texts.

Po-Yen

A second Kuchean Buddhist monk known as Po-Yen also went to Liangzhou (modern Wuwei, Gansu, China) and is said to have been well respected, although he is not known to have translated any texts.

Tocharian languages

The language of Kucha, as evidenced by surviving manuscripts and inscriptions, was Kuśiññe (Kushine) also known as Tocharian B or West Tocharian, an Indo-European language. Later, under the Uighur domination, the Kingdom of Kucha gradually became Turkic speaking. Kuśiññe was completely forgotten until the early 20th century, when inscriptions and documents in two related (but mutually unintelligible) languages were discovered at various sites in the Tarim Basin. Conversely, Tocharian A, or Ārśi was native to the region of Turpan (known later as Turfan) and Agni (Qarašähär; Karashar), although the Kuśiññe language also seems to have been spoken there.

While they were written in a Central Asian Brahmi script used typically for Indo-Iranian languages, the Tocharian languages (as they became known by modern scholars) belonged to the centum group of Indo-European languages, which are otherwise native to southern and western Europe. The precise dating of known Tocharian texts is contested, but they were written around the 6th to 8th Centuries AD (although Tocharian speakers must have arrived in the region much earlier). Both languages became extinct before circa 1000 AD. Scholars are still trying to piece together a fuller picture of these languages, their origins, history and connections, etc.[22]

Neighbors

The kingdom bordered Aksu and Kashgar to the west and Karasahr and Turpan to the east. Across the Taklamakan Desert to the south was Khotan.

Kucha and the Kizil Caves

The Kizil Caves lie about 70 kilometres (43 mi) northwest of Kucha and were included within the rich fourth-century kingdom of Kucha. The caves claim origins from the royal family of ancient Kucha, specifically a local legend involving Princess Zaoerhan, the daughter of the King of Kucha. While out hunting, the princess met and fell in love with a local mason. When the mason approached the king to ask for permission to marry the princess, the king was appalled and vehemently against the union. He told the young man he would not grant permission unless the mason carved 1000 caves into the local hills. Determined, the mason went to the hills and began carving in order to prove himself to the king. After three years and carving 999 caves, he died from the exhaustion of the work. The distraught princess found his body, and grieved herself to death, and now, her tears are said to be current waterfalls that cascade down some of the cave's rock faces.

Coinage

.jpg)

From around the third or fourth century Kucha began the manufacture of Wu Zhu (五銖) cash coins inspired by the diminutive and devalued Wu Zhu's of the post-Han dynasty era in Chinese history. It is very likely that the cash coins produced in Kucha predate the Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寳) and that the native production of coins stopped sometime after the year 621 when the Wu Zhu cash coins were discontinued in China proper.[24] The coinage of Kucha includes the "Han Qiu bilingual Wu Zhu coin" (漢龜二體五銖錢, hàn qiū èr tǐ wǔ zhū qián) which has a yet undeciphered text belonging to a language spoken in Kucha.[25][26]

Timeline

- 630: Xuanzang visited the kingdom.

Rulers

(Names are in modern Mandarin pronunciations based on ancient Chinese records)

- Hong (弘) 16

- Cheng De (丞德) 36

- Ze Luo (則羅) 46

- Shen Du (身毒) 50

- Jiang Bin (絳賓) 72

- Jian (建) 73

- You Liduo (尤利多) 76

- Bai Ba (白霸) 91

- Bai Ying (白英) 110-127

- Bai Shan (白山) 280

- Long Hui (龍會) 326

- Bai Chun (白純) 349

- Bai Zhen (白震) 382

- Niruimo Zhunashen (尼瑞摩珠那勝) 521

- Bai Sunidie (白蘇尼咥) 562

- Bai Sufabuokuai (白蘇伐勃駃) 615

- Bai Sufadie (白蘇伐疊) 618

- Bai Helibushibi (白訶黎布失畢) 647

- Bai Yehu (白葉護) 648

- Bai Helibushibi (白訶黎布失畢) 650

- Bai Suji (白素稽) 659

- Yan Tiandie (延田跌) 678

- Bai Mobi (白莫苾) 708

- Bai Xiaojie (白孝節) 719

- Bai Huan (白環) 731-789? / Tang general - Guo Xin 789

Sources

- The Chinese Book of Han

- The Chinese Book of the Later Han

- The Chinese Book of Jin

See also

- Silk Road numismatics

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Kushan Empire

- Subashi (lost city)

Footnotes

- "中印佛教交通史". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 381, n=28.

- Elias (1895), p. 124, n. 1.

- Beckwith 1987, p. 50.

- Yuanshi, chap. 12, fol 5a, 7a.

- Beckwith 1987, p. 53.

- cf. Elias and Ross, Tarikh-i-Rashidi, in the index, s.v. Kuchar and Kusan: "One MS. [of the Tarikh-i-Rashidi] reads Kus/Kusan.

- Hill (2015), Vol. I, p. 121, note 1.30.

- Hulsewé 1979, p. 163, n. 506.

- Beckwith 2009, p. xix ff.

- Daniel C. Waugh. "Kucha and the Kizil Caves". Silk Road Seattle. University of Washington.

- Grousset 1970, p. 98.

- Schafer 1963, p. 52.

- Whitfield 2004, p. 254-255.

- Picken 1997, p. 86.

- Beckwith 1987, p. 198.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 157 ff.

- Younghusband 1904, p. 152.

- Le Coq, Albert (1922–1933). Die Buddhistische Spätantike in Mittelasien. Ergebnisse der Kgl. Preussischen Turfan-Expeditionen. Berlin.

- "German Collections". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). "Kucha", in Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 449. ISBN 9780691157863.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mair & Mallory 2008, pp. 270-296, 333-334.

- The Náprstek museum XINJIANG CAST CASH IN THE COLLECTION OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM, PRAGUE. by Ondřej Klimeš (ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 25 • PRAGUE 2004). Retrieved: 28 August 2018.

- "Xinjiang, Qiuzi Kingdom - Bilingual Cash Coins". By Vladimir Belyaev (Chinese Coinage Website - Charm.ru). 11 February 2002. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "Chinese coins – 中國錢幣 § Qiuci Kingdom (1st-7th centuries)". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Bibliography

- Tredinnick, Jeremy; Baumer, Christoph; Bonavia, Judy (2012). Xinjiang: China's Central Asia. Odyssey. ISBN 978-962-217-790-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, Christopher (1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, John Edward. Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome. A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. Vol. I. 2015. CreateSpace, North Charleston, S.C., pp. 121-125, note 1.30. ISBN 978-1500696702.

- Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus Hulsewé (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 BC - AD 23 ; an Annotated Transl. of Chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. With an Introd. by M.A.N.Loewe. Brill Archive. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2008). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28372-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Picken, Laurence (1997). Music from the Tang Court (PDF). 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62100-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of Tʻang Exotics. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Younghusband, Francis (1904). The Heart of a Continent: A Narrative of Travels in Manchuria, Across the Gobi Desert, Through the Himalayas, the Pamirs, and Hunza, 1884-1894. Scribner.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kucha. |

- Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington (The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works)

- Kucha at Google Maps

.png)