Kantō kubō

Kantō kubō (関東公方) (also called Kantō gosho (関東御所), Kamakura kubō (鎌倉公方), or Kamakura gosho (鎌倉御所)) was a title equivalent to shōgun assumed by Ashikaga Motouji after his nomination to Kantō kanrei, or deputy shōgun for the Kamakura-fu, in 1349.[1] Motouji transferred his original title to the Uesugi family, which had previously held the hereditary title of shitsuji (執事), and would thereafter provide the Kantō kanrei.[1] The Ashikaga had been forced to move to Kyoto, abandoning Kamakura and the Kantō region, because of the continuing difficulties they had keeping the Emperor and the loyalists under control (see the article Nanboku-chō period). Motouji had been sent by his father, shōgun Ashikaga Takauji, precisely because the latter understood the importance of controlling the Kantō region and wanted to have an Ashikaga ruler there, but the administration in Kamakura was from the beginning characterized by its rebelliousness. The shōgun's idea never really worked and actually backfired.[2]

After Motouji, all the kubō wanted power over the whole country. The Kantō kubō era is therefore essentially a struggle for the shogunate between the Kamakura and the Kyoto branches of the Ashikaga clan.[3] In the end, Kamakura had to be retaken by force by troops from Kyoto.[1] The five kubō recorded by history, all of Motouji's bloodline, were in order Motouji himself, Ujimitsu, Mitsukane, Mochiuji and Shigeuji.[1][4]

Birth of the Kantō kubō

In the first weeks of 1336,[5] two years after the fall of Kamakura, the first of the Ashikaga shoguns Ashikaga Takauji left the city for Kyoto in pursuit of Nitta Yoshisada.[1] He left behind his 4-year-old son Yoshiakira as his representative in the trust of three guardians: Hosokawa Kiyouji, Uesugi Noriaki, and Shiba Ienaga.[2] Because the three were related to him through blood or marriage, he believed they would keep Kantō loyal to him.[2] This action formally divided the country in two, giving the east and the west separate administrations with similar rights to power. Not only did both had Ashikaga rulers, but Kamakura, which until very recently had been the seat of a shogunate, was still capital of the Kantō, and independentist feelings were strong among Kamakura samurai.

In 1349 Takauji called Yoshiakira to Kyoto replacing him with one of his sons, Motouji, to whom he gave the title of Kantō kanrei, or Kantō deputy.[1] At first the territory under his rule, known as Kamakura-fu, included the eight Kantō provinces (the Hasshū (八州)), plus Kai and Izu.[6] Later, Kantō Kubō Ashikaga Ujimitsu was given by the shogunate as a reward for his military support the two huge provinces of Mutsu and Dewa.[6]

The shōgun's deputy in the Kantō region had the vital task to keep it under control. Structurally, his government was a small-scale version of Kyoto's shogunate and had full judiciary and executive powers. Because the kanrei was the son of the shōgun, ruled the Kantō and controlled the military there, the area was usually called Kamakura Bakufu (Kamakura Shogunate), and Motouji shōgun (左武衛将軍) or Kamakura/Kantō Gosho, an equivalent title.[1] When later the habit of calling kubō the shōgun spread from Kyoto to the Kantō, the ruler of Kamakura came to be called Kamakura Kubō.[1] The Kanrei title was passed on to the Uesugi hereditary shitsuji.[1][2] The first time the title appears in writing is in a 1382 entry of a document called Tsurugaoka Jishoan (鶴岡事書安), under second Kubō Ujimitsu.[1] This term had been first adopted by Ashikaga Takauji himself, and its use therefore implied equality to the shōgun.[7] In fact, sometimes the Kanto Kubō was called Kantō shōgun.[7]

Instability of the Kantō region

This inherently unstable double-headed power structure was made even more problematic by the continuous display of independence of the Kantō region.[2] Kamakura had just been conquered and its desire of independence was still strong.[2] Also, many of the Ashikaga in Kamakura had been supporters of the shōgun's dead brother Ashikaga Tadayoshi and resented Takauji's rule.[2] Consequently, after Motouji's death, Kamakura made clear it didn't want to be ruled by Kyoto.[2] The intentions of the Kantō Ashikaga were made crystal clear by their confiscation of the Ashikaga-no-shō: the family piece of land in Shimotsuke Province that had given the name to the clan.[2][8]

Second kubō Ujimitsu and his descendants tried to expand their influence, causing a series of incidents.[2] By the time of third shōgun Yoshimitsu, the Kamakura branch of the Ashikaga clan was regarded with suspicion.[9] Tension continued to mount until it came to a head between sixth shōgun Yoshinori and fourth kubō Mochiuji.[9] Mochiuji had hoped to succeed Ashikaga Yoshimochi as shōgun and was disappointed by seeing Yoshinori rob him of the post.[9] To express his displeasure, he refused to use the new shōgun's era name (nengō).[9] In 1439 Yoshinori sent his army to the Kantō, and Mochiuji was defeated and forced to kill himself.[1]

In 1449 Kyoto made one last effort to make the system work. Shigeuji, last descendant of Motouji, was nominated Kantō kubō and sent to Kamakura.[1] The relationship between him and the Uesugi was strained from the beginning and culminated with Shigeuji's killing of Uesugi Noritada, a murder that made the Kantō province fall into chaos.[9] (See also the article Kyōtoku Incident.) In 1455 Shigeuji was deposed by Kyoto forces and had to escape to Koga in Shimōsa Province, from where he directed a rebellion against the shogunate.[9] This was the end of the Kantō kubō. The title would survive, but effective power would be in the hands of the Uesugi.

Because he no longer was Kantō kubō, Shigeuji now called himself Koga kubō. In 1457, eighth shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent his younger brother Masatomo with an army to pacify Kantō, but Masatomo was unable to even enter Kamakura.[1] This was the beginning of an era in which the Kantō and Kamakura were devastated by a series of civil wars called the Sengoku period. The 5th Kantō kubo under the Later Hōjō clan was Ashikaga Yoshiuji, his daughter, Ashikaga Ujinohime succeeded Yoshiuji after his death. Ujinohime was the last Koga Kubo after Toyotomi Hideyoshi conquered the Later Hōjō clan, she was moved to Kōnosu Palace in 1590.[10]

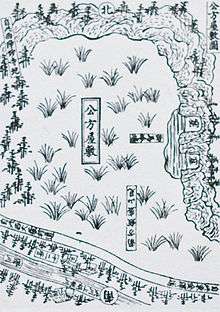

The Kantō kubō's residence in Kamakura

At the location of the former Kantō kubō residence in Kamakura stands a black memorial stele, whose inscription reads:

"After Minamoto no Yoritomo founded his shogunate, Ashikaga Yoshikane[11] made this place his residence. His descendants also resided here for well over 200 years thereafter. After Ashikaga Takauji became shōgun and moved to Kyoto, his son and second shōgun Yoshiakira decided to also live there. Yoshiakira's younger brother Motouji then became Kantō kanrei and commanded his army from here. This became a tradition for all of the Ashikaga that followed. They, after Kyoto's fashion, gave themselves the title kubō. In 1455 kubō Ashikaga Shigeuji, after clashing with Uesugi Noritada, moved to Ibaraki's Shimōsa and the residence was demolished. Erected in March 1918 by the Kamakurachō Seinendan"

The stele is at Jōmyōji 4-2-25, near Nijinohashi Bridge.[12]

It is near the bottom of an extremely narrow valley, and therefore easily defensible. The nearby Asaina Pass guaranteed an easy escape in a siege. According to the Shinpen Kamakurashi, a guide book published in 1685, more than two centuries later after Shigeuji's escape, the spot where the kubō's mansion had been was left empty by local peasants in the hope he may return.

Notes

- Kokushi Daijiten (1983:542)

- Jansen (1995:119-120)

- Matsuo (1997:119-120)

- Note that Shigeuji is an unusual reading of the characters 成氏, that would be normally be read Nariuji. The reading Nariuji is common in print and over the Internet. Authoritative texts like the Kokushi Daijiten invariably use Shigeuji.

- Gregorian date obtained directly from the original Nengō using Nengocalc Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine: (Kenmu era, 1st month)

- Iwanami Nihonshi Jiten, Kamakura-fu

- Sansom (147-148)

- Hall (1990:177)

- Hall (1990:232-233)

- 日本人名大辞典+Plus,朝日日本歴史人物事典, デジタル版. "The last Koga Kubo". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Head of the Ashikaga clan.

- Original Japanese text

References

- Hall, John Whitney (1990). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22354-6.

- Iwanami Nihonshi Jiten (岩波日本史辞典), CD-Rom Version. Iwanami Shoten, 1999-2001.

- Jansen, Marius B. (1995). Warrior Rule in Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48404-6.

- Kokushi Daijiten Iinkai. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Vol. 3 (1983 ed.).

- Matsuo, Kenji (1997). Chūsei Toshi Kamakura wo Aruku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Chūkō Shinsho. ISBN 4-12-101392-1.

- Sansom, George Bailey (January 1, 1977). A History of Japan (3-volume boxed set). Vol. 2 (2000 ed.). Charles E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 4-8053-0375-1.

- Shirai, Eiji (1976). Kamakura Jiten (in Japanese). Tōkyōdō Shuppan. ISBN 4-490-10303-4.