Battle of Kringen

The Battle of Kringen (Norwegian: Slaget ved Kringen) involved an ambush by Norwegian peasant militia of Scottish mercenary soldiers who were on their way to enlist in the Swedish army for the Kalmar War.[2]

| Battle of Kringen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Kalmar War | |||||||

Detail of Battle of Kringen, a nineteenth century national romantic depiction of the battle by Georg Nielsen Strømdal (1856-1914)[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Scottish mercenaries, under Swedish allegiance |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alexander Ramsay George Sinclair † | Lars Gunnarson Hågå | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Over 300 soldiers and conscripts | Around 400 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| About 280 |

6 killed 12 wounded | ||||||

The battle has since become a part of folklore in Norway, giving names to local places in the Ottadalen valley. A longstanding misconception was that George Sinclair, a nephew of the George Sinclair, 5th Earl of Caithness was the commander of the forces; in fact, he was subordinate to Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Ramsay.[3]

Background

The Scottish forces (Skottetoget) were partly recruited, partly pressed into service by Sir James Spens, apparently against the preferences of James VI, who favored the Danish side in the war. Two ships sailed from Dundee and Caithness in early August, met up on the Orkney Islands and sailed for Norway.[4]

Because sea routes had been blocked by Danish forces in the Kalmar War, the Scots decided to follow a land route to Sweden that other Scottish and Dutch forces had successfully used. On 20 August the ships landed in Isfjorden in Romsdal, though the pilot apparently put the forces on shore in rough terrain. The soldiers proceeded to march up the valley of Romsdalen and down into the Gudbrandsdal. [5]

Having been warned of the incursion, and probably inflamed by a massacre of Norwegian conscripts at Nya Lödöse and the events of Mönnichhoven’s march (Mönnichhoven-marsjen) earlier in July, the farmers and peasants of the Vågå, Lesja, Dovre, Fron, and Ringebu mobilized to meet the enemy. Legend has it that the sheriff of the area, Lars Gunnarson Hågå (c. 1570 – c. 1650), came into the church in Dovre with a battle axe, struck it on the floor, and shouted "Let it be known - the enemy has come to our land!" (Gjev ljod - fienden har kome til landet!).[6]

Order of battle

As the Scottish forces progressed southward, they were reportedly followed by Norwegian scouts. The Scottish forces included two companies on foot, commanded by George Sinclair and Ramsay. In recent years, it has been argued that the Scots were lightly armed but this is not probable and the bodies were looted afterwards for weapons and belongings. The Norwegians were armed with swords, spears, axes, scythes, a few muskets and some crossbows.[7]

According to folklore, the force of the Scottish troops was between 900 and 1,100 or more, but historians generally discount the estimate, placing the probable strength as low as 300. The strength of the Norwegian militia troops is estimated to have been no more than 500.[8]

Combat operations

Adolph Tidemand

There are few entirely credible accounts of the battle, but the oral history has two Norwegians on horseback following the Scottish troops, possibly on the other side of the valley. One was a woman by the name of Guri, known as Prillar-Guri to posterity; the other was an unnamed man. The man rode his horse facing backward, providing a distraction for the marching troops. When the Scots reached the narrowest section of the Gudbrandsdal at Kringen, Guri blew her horn, signaling the ambush.[9] The chosen place of assault is fairly steep, and the river runs close to what would be considered the only passable road at the time. Thus, the Scots would be trapped between the river and the mountain side, which they could not possibly scale. [10]

According to folklore, the Norwegian troops let loose logs and rocks down the valley, crushing the marching soldiers, but this is not confirmed. It is known, however, that they shot at the soldiers with crossbows and muskets. Among the first to fall was George Sinclair, apparently shot by a militiaman named Berdon Sejelstad. It is his name that is most commonly associated with the battle. Sinclair was a nephew of the Earl of Caithness and a historical figure in the Clan Sinclair.[11]

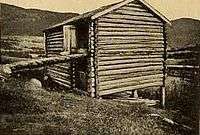

Close combat ensued, the militiamen fighting with swords, axes, scythes, and presumably other improvised weapons. Most of the Scots were killed during the battle. Some may have escaped, but others were captured. All but 14 of around 300[12] were summarily executed at Kvam in what is now Nord-Fron, the survivors then sent to Christiania for imprisonment. Those killed were thrown into a mass grave at the local cemetery, north of the Scottish barn (Skottelåven), in which captured soldiers had been held; this was later called Skottehaugen (Scottish barrow). Among the survivors were the officers Alexander Ramsay, Sir Henry Bruce, James Moneypenny, and James Scott, who were eventually repatriated.

Aftermath and legacy

at Klomstad, Kvam in Oppland county, Norway

A statue depicting Prillar-Guri is located in the community of Otta, Norway. The peak where she allegedly stood bears her name to this day, and a local broadcasting antenna is symbolically set on the top.[13]

A number of places were named after the Scottish incursion, notably along the route. The barn was destroyed by artillery fire during the intense British-German hostilities at Kvam in 1940. [14]

Captured Scottish weapons, including a pistol, a Lochaber axe, a broadsword and several basket hilt claymores, were put on display at the Gudbrandsdal War Museum at Kvam (Gudbrandsdal Krigsminnesamling i Kvam) to commemorate the battle. The display also includes a model of one of the Caithness Scots.[15]

There is evidence that some Scots may have settled in Norway and farm names may confirm that. There is a "Sinclair's Club" in Otta and there are regular re-enactments of the battle. Sinclair's grave is now a local landmark though the Norwegians at the time sought to desecrate his memory by burying him outside the church walls.[16]

Part of the bunad design for this area—known as rutaliv—is reminiscent of the Sinclair red tartan.[17]

In literature and music

Norwegian poet Edvard Storm wrote a poem that tells the story of the battle, Zinklarvisa ("Sinclair’s ballad"). Henrik Wergeland wrote a historical tragedy called Sinklars død (The Death of Sinclair). The plotline concerns Sinclair and his lady, telling of the fatal choices that led to the tragic deaths at Kringen. The Norwegian folk-rock band Folque's song "Sinclairvise" makes use of Storm's poem. [18]

The Faroese metal group Týr included a version of this song on their 2008 album Land, called "Sinklars Vísa". The ballad is still being sung in the Faroe Islands along with the traditional chain dance without any use of musical instruments.[19]

In 2009, the Norwegian rock band Street Legal released an instrumental song called "The Battle of Kringen" on their album titled Bite the Bullet.[20]

References

- Flacke, Monica (ed.). 1998. Mythen der Nationen: Ein europäisches Panorama". Berlin: Deutsches Historisches Museum.

- Slaget i Kringen, 26. august 1612 (Kulturnett Norge)

- The Battle of Kringen, 26th August 1612 (Iain Laird) Archived 19 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Magnus A. Mardal, Erik Opsahl. "Skottetoget". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 24 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Skottetoget". lokalhistoriewiki.no. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Lars Gunnarson Hågå (Store norske leksikon)

- Scottish Expedition In Norway IX 1612 (John Beveridge, M.B.E., B.D., F.S.A. Scot.)

- The Battle of Kringen, 26th August 1612 (Sinclair's Club of Otta) Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Prillar Guri (Daughters of Norway) Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Lars Løberg (31 October 2003). "Prillarguri og slektskretsen hennes". Norsk Slektshistorisk Forening. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- The Scottish Expedition in Norway in 1612 (Articles on Scottish History)

- Lasse Midttun (4 December 2014). "Skottelåven og holocaust". Morgenbladet. p. 48.

- Sverre Stølen. "Pillarguri statue by Arne Mæland". Images of Norway. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Skottelåven, eit krigsminne til ettertanke". Digitalt fortalt. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- The Battle of Kringen, 1612

- "Sinclair's Club of Otta". Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- "Råndastakk med Rutaliv". Norsk Flid Husfliden. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Sinclair's ballad". Saint Clair Sinclair. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- Herr Sinklar on Youtube, sung and dance by Havnar Dansifelag, the Faroese dance association of Tórshavn

- Petter Flaten Eilertsen and Bjørn Boge. "Reviews of Bite The Bullet". Street Legal. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Sources

This article is based in part upon Sagn, samlede i Gudbrandsdalen om Slaget ved Kringen, 26de August 1612 first published in 1838 by Hans Petter Schnitler Krag (1794-1855), pastor of the parish of Vågå.

Other sources

- Michell, Thomas History of the Scottish Expedition to Norway in 1612 (T. Nelson, London. 1886) ISBN 978-1-176-69071-4

- Gjerset, Knut History of the Norwegian People (The MacMillan Company, 1915, Volume I, pages 197 – 204) ISBN 978-1-144-62811-4

- "The Battle of Kringen", by Ann Pedersen, was featured as the cover story in the August 2012 edition of the "Viking" (USPS 611-600, ISSN 0038-1462), a Sons of Norway publication (pp. 10–14).