Krasniqi

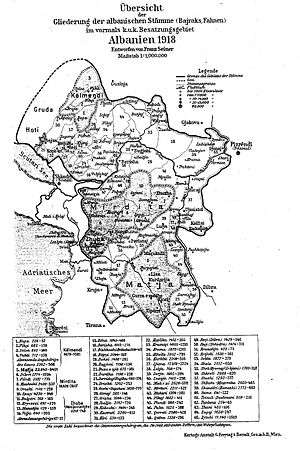

Krasniqi is a historical Albanian tribe and region in the Accursed Mountains in northeastern Albania, bordering Kosovo.[1]. The region lies within the Tropojë District and is part of a wider area between Albania and Kosovo that is historically known as Malësia e Gjakovës (Highlands of Gjakova). Krasniqi stretches from the Valbonë river in the north to Lake Fierza in the south and includes the town Bajram Curri. Members of the Krasniqi tribe are also found in Kosovo and Northern Macedonia.

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||||

| Albanian tribes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

Tribes and regions

|

||||||||||||||

|

Concepts |

||||||||||||||

|

Culture

|

||||||||||||||

Geography

The region is called Krasniqe (Krasniqja in definite Albanian) and its people are called Krasniqë. The Krasniqi region is situated in the District of Tropoja and stretches from the Montenegrin border in the north to Lake Fierza in the south, from the Mërturi region in the west to the District of Has in the east, and includes most of the upper Valbona valley. It borders on the traditional tribal regions of Bugjoni to the south, Gashi to the northeast, Nikaj-Mërtur to the west, and Bytyçi to the east.[2] The main settlements of the region are the town of Bajram Curri, Bujan, Shoshan, Kocanaj, Dragobia, Bradoshnicë, Degë, Llugaj, Murataj, Margegaj, Lëkurtaj, Bunjaj.

Krasniqi has its roots in the highlands of Gjakova, but over the centuries has spread to neighbouring areas. Thus, today many descendants of the Krasniqi fis are found within present-day Kosovo, especially in the western part (to the east of Krasniqi itself), having settled there since late 17th century.[3] On the Kumanovo Black Mountain, descendants of the Krasniqi fis were recorded in the villages of Gošince, Slupčane, Alaševce (in Lipkovo) and Ruđince (in Staro Nagoričane) in 1965.[4] There are also Krasniqi tribe members in Morani village of Skopje.[5]

Origins

Oral traditions and fragmentary stories were collected and interpreted by writers who travelled in the region in the 19th century about the early history of Krasniqi. Johann Georg von Hahn recorded the first oral tradition about Krasniqi's origins from a Catholic priest named Gabriel in Shkodra in 1850. According to this account, the first direct male ancestor of the Krasniqi was Kastër Keqi, son of a Catholic Albanian named Keq who fleeing from Ottoman conquest settled in the Slavic-speaking area that would become the historical Piperi tribal region in what is now Montenegro. His sons, the brothers Lazër Keqi (ancestor of Hoti, Ban Keqi (ancestor of Triepshi), Merkota Keqi (ancestor of Mrkojevići) and Vas Keqi (ancestor of Vasojevići) had to abandon the village after committing murder against the locals, but Keq and his younger son Piper Keqi remained there and Piper Keqi became the direct ancestor of the Piperi tribe.[6] The name of the first ancestor, Keq, which means bad in Albanian, is given in Malësia to only children or to children from families with very few children (due to infant mortality). In those families, an "ugly" name (i çudun) was given as a spoken talisman to protect the child from the "evil eye.[7] The name Kastër has also been recorded as Krasno, Kras or Krasto.

The name Kastër and its variants correspond to a settlement that appears in the Decani chrysobulls of 1330 as Krastavljane and in the defter of the sanjak of Scutari in 1485 as Hrasto. This toponym's etymology probably comes from the Slavic word hrasto (oak).[2][8] It had ten households and its head household was that of Petri, son of Gjonima. One of the household heads, Nika Gjergj Bushati was related to the Bushati fis.[9] Villages that later were part of Krasniqi that appear in the defter of 1485 are Shoshan (20 households) and Dragobia (six households).[9] These villages were not part of the same community or the same administrative unit as other tribes of northern Albania and Montenegro like Hoti or Piperi which were in the process of their final formation at that time. It is also unclear what the relation of the people of these settlements is to the first historical ancestor of Krasniqi who lived about 70 years later.

Krasniqi is a fis (tribe) of two different patrilineal ancestries. Most brotherhoods of Krasniqi come from Kolë Mekshi who lived in the mid 16th century. After 1550, he and his brother Nikë Mekshi are recorded as the first, historical, direct ancestors of the Krasniqi and Nikaj tribes. To Kolë Mekshi trace their descend the Kolmekshaj brotherhoods and their branches. They form the population of Shoshan and Dragobia. They also founded Bradoshnicë, Degë, Kocanaj, Murataj and also form half of the village of Margegaj. The other half of Margegaj descend from its founder Mark Gega.[10] The inhabitants of Kolgecaj (renamed to Bajram Curri in 1957), Lëkurtaj and Bunjaj stem from other brotherhoods that were unrelated to the Kolmekshaj, but later were included in the tribe.[11]

History

As for much of its history Krasniqi was a Catholic community, its early history is traced through official reports of Catholic clergy to the Vatican. The tribe's name was recorded for the first time in 1634 as Crastenigeia in a report of the Catholic bishop Gjergj Bardhi. Four years later, his nephew bishop Frang Bardhi passed through Krasniqi territory and noted that they had their own church. The settlement of Krasniqi at that point had 60 households with 475 people. He also remarked the extreme poverty that the Krasniqi were enduring.[12]

Heavy taxation against Catholics and Ottoman repression kickstarted the conversion of the population to Islam at the end of the 17th century. This process was mostly finished by the middle 19th century, but the Krasniqi community in and around the towns of Gjakova and also Prizren remained Catholic. From these Krasniqi families stem Catholic archbishop Matej Krasniqi and apostolic vicar Gaspër Krasniqi. The Catholics of Krasniqi were put under the Austrian kultursprotektorat in the late 1760s, which gave some religious freedom to Catholics in the Ottoman Empire under the state protection of the Austrian Empire. This allowed for the Catholic parishes of Gjakova and Prizren to rebuild their churches and schools.

Traditions

The tribe's (historical) patron saint is St. George,[13] whom they still revere after Islamization.[14]

Notable people

- Bajram Curri, politician

- Shpend Dragobia, rebel

- Rexhep Krasniqi, Albanian MP, Minister of Education, and anti-communist

- Matej Krasniqi, Catholic Archbishop of Skopje

- Gaspër Krasniqi, Catholic priest

- Binak Alia, from Mulosmanaj clan of Krasniqi, guerrilla fighter of the Albanian Revolt of 1845 and League of Prizren

- Mic Sokoli, Guerrilla fighter

- Haxhi Zeka, Member of the League of Prizren

- Behgjet Pacolli, a former President of the Republic of Kosovo and is the President and CEO of Mabetex Group, a Swiss-based construction and civil-engineering company.

- Dah Polloshka, rebel

- Mark Krasniqi, Kosovar academic in ethnology and anthropology

- Luan Krasniqi Boxer

- Shefqet Krasniqi Kosovar Muslim cleric

See also

- List of Albanian tribes

- Krasniqi (surname)

References

- Arshi Pipa (1978), Albanian folk verse: structure and genre, Volumes 17-19, Trofenik, p. 126

- Robert Elsie (2010), Historical Dictionary of Albania (PDF), Historical Dictionaries of Europe, 75 (2 ed.), Scarecrow Press, p. 248, ISBN 978-0810861886, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-06

- Karl Kaser (2012), Household and Family in the Balkans: Two Decades of Historical Family Research at University of Graz, Studies on South East Europe, 13, LIT Verlag, p. 124, ISBN 978-3643504067

- Naučno društvo Bosne i Hercegovine: Odjeljenje istorisko-filoloških nauka. 26. 1965. p. 199.

Arbanasa fisa Krasnića ima u selima: Gošnicu, Slupćanu, Alaševcu, Ruđincu.

- https://mk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%7C quote:Исалар (од фисот Красниќ во северна Албанија).}}

- von Hahn, Johan Georg; Elsie, Robert (2015). The Discovery of Albania: Travel Writing and Anthropology in the Nineteenth Century. I. B. Tauris. p. 125. ISBN 1784532924.

- Shkurtaj, Gjovalin (2009). Sociolinguistikë e shqipes: Nga dialektologjia te etnografia e të folurit [Socio-linguistics of Albanian: from dialectology to the ethnography of spoken language]. Morava. p. 390. ISBN 978-99956-26-28-0. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- The Tribes of Albania,: History, Culture and Society. Robert Elsie. p. 161.

- Pulaha, Selami (1974). Defter i Sanxhakut të Shkodrës 1485. Academy of Sciences of Albania. p. 146,179. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Progni, Dodë (2003). Nikaj-Merturi: vështrim historik [Nikaj-Mërtur: an historical account]. Shtjefni. ISBN 9992782641. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Pulaha, Selami (1975). "Kontribut për studimin e ngulitjes së katuneve dhe krijimin e fiseve në Shqipe ̈rine ̈ e veriut shekujt XV-XVI' [Contribution to the Study of Village Settlements and the Formation of the Tribes of Northern Albania in the 15th century]". Studime Historike. 12: 132. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Zamputi, Injac. RELACIONE MBI GJENDJEN E SHOIPERISE VERIORE DHE TE MESME NE SHEKULLIN XVII [Reports on the Situation in Northern and Central Albania in the mid 17th century vol.2]. University of Tirana. p. 148. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Mitološki zbornik. 12. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. p. 41.

- Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti (1957). Posebna izdanja. 270. p. 24.

Исламизо- вани Арбанаси Краснићи и сада поштују св.