Kirche am Hohenzollernplatz

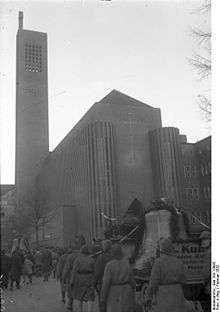

Kirche am Hohenzollernplatz (Church at Hohenzollernplatz ) is the church of the Evangelical Congregation at Hohenzollernplatz, a member of today's Protestant umbrella Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia. The church is located at the eastern side of Hohenzollernplatz square in the locality of Wilmersdorf, in Berlin's borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. The building is considered one of the main pieces of Brick Expressionism.[1] And it is a testimonial of unique quality of expressionist church architecture in Berlin.[2] The naming of the church after the square was originally a solution for the time being, until another name might be chosen. Meanwhile, the name has become a brand, even though the debate goes on.[2]

| Kirche am Hohenzollernplatz | |

|---|---|

The main entrance towards Hohenzollernplatz and the rectory built right adjacent to the church. | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | United Protestant |

| District | Sprengel Berlin (region), Kirchenkreis Wilmersdorf (deanery) |

| Province | Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia |

| Location | |

| Location | Wilmersdorf, a locality of Berlin |

| Geographic coordinates | 52°29′39″N 13°19′37″E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Ossip Klarwein with Fritz Höger |

| Style | Brick Expressionism |

| Completed | 1933, destroyed 1943, gradually reconstructed until 1965 |

| Specifications | |

| Spire height | 66 meters |

| Materials | clinker brick |

Church and architect

Due to the high number of new parishioners moving in during the first third of the 20th century the existing three churches, to wit Auenkirche, High Master Church, and Church of the Cross, never sufficed to contain the congregants of the Evangelical Wilmersdorf Congregation (German: Ev. Kirchengemeinde Berlin-Wilmersdorf).

In 1927 the then wealthy congregation, whose parish then comprised the locality of Wilmersdorf, therefore decided to build an additional church in the north of its parish.[3] The congregation tendered a competition and the architecture firms of Otto Bartning, Hellmuth Grisebach, Fritz Höger, Otto Kuhlmann (in German), Leo Lottermoser and Hans Rottmayr handed in their projects.[3]

Höger prevailed with the design of the architect Ossip Klarwein, who started to work with Höger by 1921, with the design altered by the latter.[4] Klarwein was chief designer (German: Hauptentwurfsarchitekt[5]) in Höger's firm and – according to his contract – all his designs were issued under Höger's name.[4]

The congregation commissioned the Hamburg-based architecture firm of Höger. So Klarwein moved to Joachim-Friedrich-Straße No. 47 (Berlin), shortly before the constructions started, in order to supervise the realisation of the design. The construction lasted from 1930 to 1933.[6] On 19 March 1933 the church was inaugurated, soon after Klarwein, his wife and son Mati emigrated to Mandatory Palestine, because of the Nazi takeover (Machtergreifung).

The design of the church

The modern design was much under debate already long before the constructions started.[7] The basic structure of the church is a concrete skeleton, clad by the façades, finely structured on the long sides and of even masonry on the narrow sides, all in clinker brick. Höger preferred that material.[6] The hip roof of verdigris copper contrasts with the dark reddish brick. The slim and high tower, being a landmark seen through much of Hohenzollerndamm thoroughfare and other streets, is connected to the northeastern corner of the actual building.[2]

The actual prayer hall is elevated, because the ground floor harbours a fellowship hall. The entrance at the western side is flanked both sides by the cladding of the two round staircases. A semicircular flight of stairs leads to the ogival main portal, which announces the dominant forms of the interior. The complete appearance is a good eye-catching flank to the eastern side of the square of Hohenzollernplatz.[1]

The interior of the huge nave is structured by 13 girders of ferroconcrete, which end as pilasters on the ground. Starting from the entrance in the west the girders give the impression to taper towards the east. The ogival form of the girders grants the interior a kind of Gothic, very modern though, appeal. This form evoked certain mysticism, which is unusual for the rather sober Protestant church architecture of those years. This and the modern as well as voluminous appearance earned the church the nickname Powerhouse of God (German: Kraftwerk Gottes).[2]

The Allied bombing of Berlin in World War II inflicted severe damage on the church. On 22 November 1943 the church burnt out.[1] The reconstruction proceeded gradually until 1965. Services were then held in the fellowship hall below the actual prayer hall. The architect Gerhard Schlotter submitted the church to a renovation and rebuild in 1990/1991, in order also to prepare it for its usage for exhibitions of contemporary art.[2] Schlotter brightened up the prayer hall in the colours used before the destruction.[1]

Furnishings

Prof. Hermann Sandkuhl (in German) created sgraffiti, displaying different figures in the intermediate spaces between the pilasters, all lost in the fire in 1943.[8] The tympanon of the last, somewhat smaller girder, opening towards the oriented quire, showed a painting of the Sermon on the Mount, depicting Jesus of Nazareth with a corona of light by Erich Waske (in German), which was also lost in 1943.[8] The prayer hall is illuminated by three long windows in the quire. The original windows were blasted away by the bombs. In 1962 Sigmund Hahn designed a new central quire window. In the course of the renovation of 1990/1991 Achim Freyer (in German) added a new right and left colourful quire window.[9] Höger's Baptismal font of clinker brick with gold paintings on it survived. Regina Roskoden's abstract basalt sculpture of an angel, graphics by Max Pechstein and a painting of the crucifixion by Hermann Krauth are shown in a by-room. Considerable offertories of the parishioners enabled to buy a new organ of 60 registers by E. Kemper & Sohn, installed after 1965 and requiring the removal of the second western loft gallery of seats.[8]

Congregation today

On 1 April 1946 the northern part of the parish of the Wilmersdorf Congregation was constituted as today's Congregation at Hohenzollernplatz (German: Kirchengemeinde am Hohenzollernplatz), becoming the proprietor of the ruined church.[8] Since 1987 the church is also open for exhibitions of contemporary art, two of which are shown every year. Art plays an important role for the congregation, thus there are also services referring to art. In 1991 the organ builder Sauer reintonated the Kemper organ, which is regularly used in the services and for concerts.[9] Since November 2008 every Saturday at 12.00 the "NoonSong" – a 30 minutes lasting liturgy sung by the professional vocal ensemble sirventes berlin – attracts hundreds of listeners.

Trivia

The church is nicknamed "God's power house" ("Kraftwerk Gottes") by the Berlin inhabitants due to its appearance.

References

- Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger, Michael Bollé, Ralph Paschke et al., Handbuch der Deutschen Kunstdenkmäler / Georg Dehio: 22 vols., revis. and ext. new ed. by Dehio-Vereinigung, Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 22000, vol. 8: Berlin, p. 496. ISBN 3-422-03071-9.

- Karin Köhler, Christhard-Georg Neubert and Dieter Wendland, Kirchen und Gotteshäuser in Berlin: Eine Auswahl, Berliner Arbeitskreis City-Kirchen (ed.), Berlin: Evangelische Kirche in Berlin-Brandenburg, 2000, pp. 76–78. ISBN 3-931640-43-4.

- Günther Kühne and Elisabeth Stephani, Evangelische Kirchen in Berlin (11978), Berlin: CZV-Verlag, 21986, pp. 310–312. ISBN 3-7674-0158-4.

Notes

- Sibylle Badstübner-Gröger, Michael Bollé, Ralph Paschke et al., Handbuch der Deutschen Kunstdenkmäler / Georg Dehio: 22 vols., revis. and ext. new ed. by Dehio-Vereinigung, Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 22000, vol. 8: Berlin, p. 496. ISBN 3-422-03071-9.

- Karin Köhler, Christhard-Georg Neubert and Dieter Wendland, Kirchen und Gotteshäuser in Berlin: Eine Auswahl, Berliner Arbeitskreis City-Kirchen (ed.), Berlin: Evangelische Kirche in Berlin-Brandenburg, 2000, p. 77. ISBN 3-931640-43-4.

- Karin Köhler, Christhard-Georg Neubert and Dieter Wendland, Kirchen und Gotteshäuser in Berlin: Eine Auswahl, Berliner Arbeitskreis City-Kirchen (ed.), Berlin: Evangelische Kirche in Berlin-Brandenburg, 2000, p. 76. ISBN 3-931640-43-4.

- Myra Warhaftig (Hebrew: מירה ווארהפטיג), Sie legten den Grundstein. Leben und Wirken deutschsprachiger jüdischer Architekten in Palästina 1918–1948, Berlin und Tübingen: Wasmuth, 1996, p. 294. ISBN 3-8030-0171-4

- Cf. Ernst-Erik Pfannschmidt, another architect employed with Höger, in his Letter to Eckhardt Berckenhagen, 29 June 1977, who then prepared the exhibition on the occasion of Höger's 100th anniversary in the Kunstbibliothek Berlin, an institution of the Berlin State Museums of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation.

- Günther Kühne and Elisabeth Stephani, Evangelische Kirchen in Berlin (11978), Berlin: CZV-Verlag, 21986, p. 310. ISBN 3-7674-0158-4.

- See the number of articles in architectural reviews, from 1928 on, in: Entry in Berlin's list of monuments with further sources (in German).

- Günther Kühne and Elisabeth Stephani, Evangelische Kirchen in Berlin (11978), Berlin: CZV-Verlag, 21986, p. 312. ISBN 3-7674-0158-4.

- Karin Köhler, Christhard-Georg Neubert and Dieter Wendland, Kirchen und Gotteshäuser in Berlin: Eine Auswahl, Berliner Arbeitskreis City-Kirchen (ed.), Berlin: Evangelische Kirche in Berlin-Brandenburg, 2000, p. 78. ISBN 3-931640-43-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kirche am Hohenzollernplatz (Berlin). |