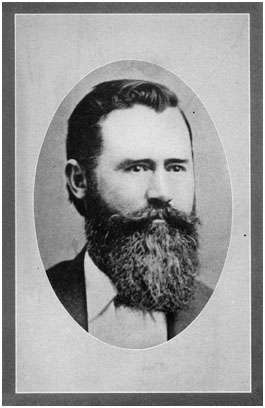

King Woolsey

King S. Woolsey (ca. 1832 - June 30, 1879) was an American pioneer rancher, prospector and politician in 19th century Arizona. Woolsey Peak and other features of Arizona geography have been named after him, but he has also been criticized by historians for brutality in his battles with Apache native Americans.

Biography

Woolsey, born in Alabama, moved to Arizona from California in 1860, first at Yuma, Arizona and Fort Yuma, where he sold supplies to the U.S. Army. In 1862, Woolsey and a partner bought the Agua Caliente ranch, near the Gila River in what is now western Maricopa County, Arizona. They dug irrigation ditches from the river and planted crops. Woolsey operated Arizona's first flour mill at Agua Caliente, and brought the first threshing machine into the territory.[1] Woolsey Peak in the Gila Bend Mountains - a prominent landmark near his ranch - and the Woolsey Peak Wilderness Area, were both later named to honor him.

American Civil War service

In 1863, Woolsey joined the Walker Party to explore the Hassayampa River for gold. Soon after, he homesteaded and established the Agua Fria ranch, near present-day Dewey, Arizona. Woolsey is most famous (or notorious) for his forays against the native Indians in central Arizona. During the American Civil War, after 1863, practically all troops were withdrawn from Arizona, and Indian attacks on white settlers and their property increased.

In 1864, after a series of livestock thefts, Woolsey led a group of settlers to the vicinity of present-day Miami, Arizona, where they encountered a large party of Tonto Apaches. In the ensuing Battle of Bloody Tanks, the settlers killed (and later scalped) at least 24 Indians, with the loss of one settler. It appears that the settlers opened fire first, during a parley.[2] After this fight, Woolsey was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel of the Arizona territorial militia by Governor John N. Goodwin.

Later in 1864, Woolsey and several other men were working their mining claims in the Bradshaw Mountains. They were apparently confronted by a large party of Indians, probably Yavapais. Woolsey called for a parley, after first hiding a sack of pinole poisoned with strychnine nearby. As he had hoped, the Indians found the poisoned meal and ate it while he talked to their chiefs. As the poison took effect, and the others fled, his men opened fire on them. This encounter was later called the Pinole Massacre.[3]

The first Territorial Legislature voted a commendation to King Woolsey and his volunteers for, inter alia, "taking the lives of numbers of Apaches, and destroying the property and crops in their country." [4] In 1864 Woolsey was elected to the first Legislature of the Territory of Arizona, and was re-elected to several subsequent legislatures.

After the war

The creation of the Democratic Party in Arizona Territory was largely due to Woolsey's efforts. Since its creation by a Republican-dominated Congress in 1863, the Republicans had controlled Arizona politics. Woolsey called a meeting of like-minded Democrats in February 1873 in Tucson. Presiding at the meeting, he introduced a series of resolutions which led to organization of the Democratic Party in the Arizona Territory. He was the Democratic candidate for Territorial Delegate to the U.S. Congress in the 1878 election, but was defeated.

Woolsey died of a heart attack at his Agua Fria ranch in 1879. He was 47 years old. He is buried in Pioneer and Military Memorial Park in Phoenix.

King S. Woolsey, was, in all respects, a big man. He was a typical Westerner, bold, resolute and energetic. A natural leader of men, he was successful, not only in his Indian expeditions, but also in his business enterprises. His activities were known and felt in all parts of the Territory up to the time of his untimely death. Among the early pioneers of Arizona he stands out the most conspicuous figure of them all. [5]

Family

Woolsey took a Yaqui woman named Lucy Martinez as a mistress, and they had a daughter named Conception. Woolsey also had a biological daughter, Clara Woolsey, who Woolsey did not recognize as legitimately his. Clara had two children, Julio and Clara.[6]

See also

References

Kate Ruland-Thorne, 2007, Gold, Greed and Glory: the Territorial history of Prescott and the Verde Valley, 1864-1912. Baltimore, Publish America, ISBN 1-4137-9322-3.

Thomas Edwin Farish, 1915-1918, History of Arizona, available online at http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/swetc/

- Yuma Sun, September 28, 2007

- Kate Ruland-Thorne, op. cit., pp. 46-47

- Kate Ruland-Thorne, op. cit., pp. 48-49

- Thomas Edwin Farish, op. cit.

- Thomas Edwin Farish, op.cit.

- Barrios, Frank M. Mexicans in Phoenix. Arcadia Publishing, 2008, pages 10, 81.