King Leopold II statue (Ostend)

The statue of King Leopold II in the Belgian city of Ostend is located on the Royal Galleries by the beach.[1] King Leopold II of Belgium was commemorated here as a benefactor of Ostend and of the Belgian Congo. The inauguration was on 19 July 1931.[1]

| King Leopold II statue | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Alfred Courtens |

| Year | 1931 |

| Location | Ostend, Belgium |

| 51°13′38″N 2°54′17″E | |

.jpg)

The statue was vandalised in 2020 as part of the global Black Lives Matter movement after the death of George Floyd. A petition to remove such statues is ongoing until 30 June 2020, the 60th anniversary of Congo's independence from Belgium.[2][3][4][5]

History

While Leopold was alive, Thomas Vinçotte produced a portrait bust which is now in the Royal Greenhouses of Laeken.[6]

Shortly after Leopold's death in 1909, plans were started to honor him, as benefactor of Ostend and of the Belgian Congo.[6] After the First World War, the city government started work on plans for a statue.[6] Sculptor Alfred Courtens (1889-1967), was commissioned, together with his brother, the architect, Antoine Courtens (1899-1969).[7][1] The City Council may have hoped to regain the dynasty as summer residents but after Leopold II's death, Ostend's status as a royal summer residence quickly crumbled.[6][7] On 22 September 1981 the statue was declared a protected monument.[7]

Description

The monument is known locally as "De Drie Gapers".[7][8] The middle of the three passages was made on the sea side.[9] The monument has an important architectural part that roughly consists of a voluminous upright column, with two horizontal bases on the left and right.[9] This gives a form of a kind of double L monogram (two L's turned away from each other), the monogram that Leopold II often used.[9] On top in bronze, Leopold II sits in military uniform on horseback looking over the North Sea.[9] At the bottom left a larger than life sculptural group, also in bronze, depicting "Thanks of the Congolese to Leopold II for freeing them from slavery among the Arabs".[9][1] On the right, a pendant, depicting "Tribute of the Ostend fishing population".[1]

Controversy

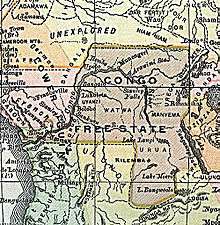

Congo Free State

Leopold was the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, a private project undertaken on his own behalf.[10] He used explorer Henry Morton Stanley to help him lay claim to the Congo, an area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[10] At the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the colonial nations of Europe authorised his claim by committing the Congo Free State to improving the lives of the native inhabitants.[10]

From the beginning, Leopold ignored these conditions and millions of Congolese inhabitants, including children, were mutilated and killed.[10] He used great sums of the money from this exploitation for public and private construction projects in Belgium during this period.[10] He donated the private buildings to the state before his death.[10]

Leopold extracted a fortune from the Congo, initially by the collection of ivory, and after a rise in the price of rubber in the 1890s, by forced labour from the natives to harvest and process rubber.[10] Under his regime millions of Congolese people died.[10]

Reports of deaths and abuse led to a major international scandal in the early 20th century, and Leopold was forced by the Belgian government to relinquish control of the colony to the civil administration in 1908.[10]

Vandalism

The Equestrian statue of King Leopold II has been vandalised in 2004 and 2020.[2][3][4][5] In 2004 an activist group, De Stoete Ostendenoare, symbolically cut off a bronze hand from one of the kneeling Congolese slaves who, as part of the 'Gratitude of the Congolese' group in the monument, honours Leopold II.[1] This was a reference to how Congolese slaves' hands were cut off if they did not produce enough rubber during Leopold's colonial regime.[1] The activists were willing to give the hand back if a historically correct sign would be placed near the statue.[11]

On 9 June 2020, Ostend mayor Bart Tommelein said that the city council "takes the fight against racism very seriously" but "replacing or removing statues will not happen".[12]

See also

References

- "EQUESTRIAN STATUES".

- Teri Schultz (5 June 2020). "Belgians Target Some Royal Monuments In Black Lives Matter Protest". NPR. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Al meer dan 16.000 handtekeningen voor petitie om standbeelden Leopold II uit Brussel weg te nemen, Tommelein wil beeld in Oostende niet verwijderen". Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 3 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Het Debat. Moeten standbeelden van Leopold II en andere bedenkelijke historische figuren verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld?". Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Burno Struys (6 June 2020). "Dit zijn de organisatoren van de Belgische Black Lives Matter-betogingen". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Kempenaers, Jan. Belgian Colonial Monuments. ISBN 9492811502.

- Hostyn, Norbert. Monumenten, beelden & gedenkplaten te Oostende: Het Leopold II-monument op de zeedijk. pp. 218–219.

- "De Drie Gapers Oostende". Bezienswaardigheden. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Silverman, Debora L. (2013). "Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism, Part III". West 86Th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture. 20 (1): 31. doi:10.1086/670975. JSTOR 10.1086/670975.

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. ISBN 978-0618001903.

- Douglas De Coninck (11 August 2014). "Hoe Oostendse activisten met een afgehakte hand de puntjes op de i zetten". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Campaign launched by teenager to remove statues of Congo coloniser Leopold II gains pace in Belgium". Retrieved 9 June 2020.