Kilbirnie Loch

Kilbirnie Loch (NS 330 543), is a freshwater Loch situated in the floodplain between Kilbirnie, Glengarnock and Beith, North Ayrshire, Scotland. It runs south-west to north-east for almost 2 km (1.2 mi), is about 0.5 km (0.31 mi) wide for the most part and has an area of roughly 3 km2 (761 acres). It has a general depth of around 5.2 metres (17 feet) to a maximum of around 11 metres (36 feet). The loch is fed mainly by the Maich Water, which rises in the Kilbirnie Hills near Misty Law (507m or 1663 feet), and is drained by the Dubbs Water that runs past the Barr Loch into Castle Semple Loch, followed by the Black Cart, the White Cart at Renfrew and finally the River Clyde. The boundary between East Renfrewshire and North Ayrshire, in the vicinity of the loch, runs down the course of the Maich Water along the northern loch shore to then run up beside the Dubbs Water.

| Kilbirnie Loch | |

|---|---|

The loch from the southern end | |

| Location | North Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°45′N 4°41′W |

| Lake type | freshwater loch |

| Primary inflows | Maich Water |

| Primary outflows | Dibbs Water |

| Basin countries | Scotland |

| Max. length | 2 km (1.2 mi) |

| Max. width | 0.5 km (0.31 mi) |

| Surface area | 3.08 km2 (1.19 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 5.2 m (17 ft) |

| Max. depth | 105 ft (32 m) |

| Surface elevation | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Islands | The Cairn crannog (destroyed) |

| Settlements | Kilbirnie, Beith, Glengarnock |

History

Origins and placenames

Hector Boece (1465–1536) is the first to publish a reference to the loch, using the name 'Garnoth', in his book of 1527 the 'Historia Gentis Scotorum' (History of the Scottish People), saying that nocht unlike the Loch Doune full of fische.[2] There is a long history of drainage schemes and farming operations in the area, with co-ordinated attempts dating from about 1691 by Lord Sempill, followed by Colonel McDowal of Castle Sempil in 1774, James Adams of Burnfoot, and by others.[3] Until these drainage works the two lochs nearly met and often did during flooding, to the extent that early writers such as Boece, Hollings and Petruccio Ubaldini regarded the lochs as one, using the name 'Garnoth' or 'Garnott'.[3] The Castle Semple and Barr Lochs lie in an area previously covered until more recently by one large loch known as 'Loch Winnoch', however by the end of the 18th century silt from the River Calder had divided the loch into two. In 1814 Barr Loch and the Aird Meadow was bunded and drained, however after WW2 the area was gradually abandoned for agriculture.[4]

'Loc Tancu' is seemingly the earliest recorded name from circa 1210 and the name 'Loch Tankard', 'Thankard' or 'Thankart' was used locally.[2][5] A farm named 'Unthank' or 'Onthank' existed until the 19th century near to the old Nether Mill opposite the lost 'Cairn' island and together with 'Thankard' may be derived from 'Tancu'. The term 'Garnoth' has also been used and may derive from 'Garnock'. In early feudal times many Flemings were granted land in the valley of the Clyde, including an individual named 'Thankard', who gave his name to Tankerton, Wice in Wiston, Lambin in Lamington and William, the ancestor of the family of Douglas.[6][7] A Lochend Farm existed in the area that is now occupied by Glengarnock.

Early maps, circa 1600, show the two lochs with separate names, but effectively a continuous body of water.[8]

The place name 'Kerse' used for the farms and the bridge at the northern end of the loch refers in Scots to 'Low and fertile land adjacent to a river or loch'.[9] The old Barony of Kersland was held by the Ker (latterly Kerr) family; by chance or by association with this site the surname Kerr may derive from the nature of the location. The term 'Loch of Kilbirnie' is sometimes found in books, on older maps, etc.

Ownership

The monks of Paisley Abbey once held the lands between the Maich and Calder and it is likely that the old toll route, using the toll point of Maich, came through this area.[10]

The loch is situated in the Parish of Kilbirnie and the ancient Barony of Glengarnock once held by the Cuninghams, a cadet branch of the Earls of Glencairn from Kilmaurs; it later formed part of the estate of the Crawfurds of Kilbirnie as a result of the Honourable Patrick Lindsay acquiring, in 1677, the Glengarnock estates and marrying Margaret, heiress of Sir John Crawfurd of Kilbirnie. Their son became the first Viscount Garnock and in 1707 he had the baronies of Kilrbirnie and Glengarnock combined under into the 'Barony of Kilbirnie'.[2][5]

As stated, the loch once belonged to the Cunninghames of Glengarnock, but the Craufurds of Kilbirnie disputed their rights over rowing and fishing;[5] these families broke one another's boats, etc. until inter-marriage solved the problem. Both clans had the loch included in their charters.[2][11]

The boundary shown in 1654 between the baronies of Kilbirnie and Renfrew did not follow the Maich Water and Dubbs Water, it even ran into the loch itself, reflecting the aforementioned disputes.[12]

In 1775 Armstrong's map records 'Loch Tankard' as the property of the Earl of Crawford, but holds of the Prince of Wales.[13]

In the 1860s the loch was owned by James, Earl of Glasgow.[14] The solum of the loch is now owned by Scottish Enterprise, however 'riparian owners' possess the loch shoreline and have certain duties and obligations as well as rights.[11] North Ayrshire Council own the land at the southern end of the loch, Network Rail own the land on the eastern shore of the loch along the side of the main railway line to Glasgow and private owners hold land to the west and north. The salmon fishing rights are held by the Crown. the Chivas Regal (Pernod Ricard Ltd) own the strip of land running from the railway to the loch shore opposite their whisky bond site.

The Cairn Island

This was the only island on the loch and was thought as late as the 1860s[14] to have been built by one of the lairds as a retreat for swans, geese, or other water fowl during the breeding season. It had a fordable causeway leading out to it and rose about 2.5 feet above the water level, clothed in trees and grasses.[3] The southern end of the loch was the site of infill with slag and other wastes from 1841 onwards. By the 1860s 'The Cairn' had become distorted and shifted by the movement of the sediment on the loch caused by the weight of the infill, revealing the presence of a crannog lake dwelling (see 'Archaeology'). Infill operations completely destroyed then island in due course.[3][15]

An artificial island was created at the south-east end of the loch for nesting birds in the 1980s.

Flax and steel

Lochside Farm was present on the north-west side of the loch in the 19th century, lying below and to the south-west of Lochrig, later Lochridge, as shown on the 19th century OS map; a 'Flax Pond' for rhetting flax, as part of the process of linen manufacture, is also shown nearby on the loch bank; it is now visible as a wet area dominated by rushes. The firm of William & James Knox, linen thread manufacturers, established as early as 1788, are still based in Kilbirnie. Scotland was amongst the first producers of flax.[16] The road running down to the loch here from Baxter Head became known locally as the 'Shanks-McEwan Road' after the company that was contracted to remove the old steelwork's slag heaps.

The Glengarnock Ironworks and the later steelworks produced slag and other wastes which were disposed of into the loch, significantly reducing its size and depth.[6][17] The south-west section of the loch is still hazardous due to slag lying close to the surface. The Dubbs Water was originally dug as a canal in the late 18th century for transporting coal and iron ore to the steelworks and to take finished products to their markets. Roads were unsuitable for transport of heavy goods at the time and the railways were in their infancy.

Loch Riggs

This was a collier's hamlet near the Maich Water. The Loch Riggs Colliery was abandoned in 1808 when the works were flooded. The rich coal seams ran under the loch and were never further exploited. In 1900 the old colliery waste was encountered by the navvies during the construction of the railway between Lochwinnoch and Kilbirnie. A nearby road was locally known as the 'Back-Stair-Heid' and it has been suggested that this refers to the location of a pit ladderway used to carry coal out of the mines before winding engines were in use.[18]

Geology

The solid geology in the lower catchment area is carboniferous limestone. Higher ground to the North and South is mainly basalt. The drift geology includes a layer of peat to the North and boulder clay and lake alluvium over the lower catchment zone. Soils are alluvium to the North and Southeast, whilst to the East and West poorly drained non-calcareous gley soils predominate.[19]

Archaeology

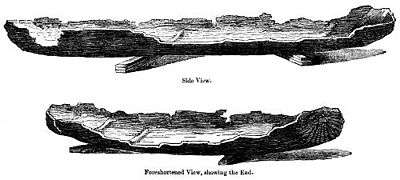

In 1868 a crannog, its causeway and up to four logboats were revealed at the south-west corner of the loch as a result of dumping of furnace-slag from the now closed ironworks,[6] causing the lake-bed sediments to be pushed upwards so that the crannog and logboat remains were exposed above the surface of the water. A site known as 'The Cairn' was already recognised, being exposed during exceptionally low water conditions.[20] The crannog and causeway are marked on the 1st edition of the OS 6-inch map (Ayrshire, sheet viii) at NS 3238 5356. Two of the boats were recorded in some detail. The most complete of the logboats was 18' (5.5m) in length, 3' (0.9m) in breadth and circa 2' (0.6m) in 'depth'; about 2' (0.6m) had been lost from the bow. The stern was 'square'. A tripod pit and a bronze ewer were found in one of the boats, now preserved at the Royal Museum of Scotland. These items were not contemporary with the logboat.[21] The boat itself disintegrated rapidly on exposure to air. Part of a second logboat was subsequently found 'close by the island'; its fate is not recorded. This boat was worked from 'oak'.[22]

In May 1952 part of a logboat was found on the west side of the loch and on the property of the Glengarnock Steelworks; slag-dumping operations were responsible for revealing it. Analysis of pollen from the mud found in the timber suggested that the logboat was from between about 3000 and 700bc. The surviving portion of the boat was donated to Paisley Museum.[23]

The southern end of the loch was the site of infill with slag and other wastes from 1841 onwards, the greatest loss of open water being between 1859 and 1909. By 1930 the southern end infill had largely ceased, however infill from the west bank continued for some time.[15]

Access

At the Kilbirnie end the loch can be accessed by following the B777 to the Lochshore Industrial Estate. This provides ample parking and the road leads to the boat launching area in the south-west corner of the loch.

At the Beith end the unclassified 'Kerse' road runs between Beith and the A760 enables access to the northern shore of the loch. Parking along the roadside is difficult. At the railway bridge (NS 338 552) close to the old station is a rough track which leads down to the lochside and parking in this area is hazardous. The track and the area at the bottom are used by the local Kayak Club. Access to the land along the north shore is dependent upon the good will of the landowner at Kerse Bridge Kennels.

Part of the Sustrans National Route 7 runs close to the loch, starting at Paisley Canal railway station and following the same route as National Route 75 until Johnstone, passing Elderslie and continuing south-west to Kilbarchan, Lochwinnoch and Kilbirnie, passing by Castle Semple, Barr as well as Kilbirnie Loch. Cycle paths runs on down via Glengarnock, Dalgarven and Kilwinning to Ardrossan, Irvine and beyond.[24][25]

Transport

The loch was used for pleasure cruises in the 18th century and coal was once carried from the Kilbirnie side across the loch to Beith. Hugh Stevenson used to have the "sole right to howk coal in Brodie's Glen" up the Maich Water. Hugh Stevenson transported the coal down to the loch, and ferried it across to a jetty which was near the mouth of the Mains Burn, then locally known as the Back Burn, and from there it was taken up to Beith by cart.[19]

A passenger ferry also ran across the loch at one time, most likely from near the old Lochside Farm, which is reached by a lane from Stonyholm, across to the Bark Mills delta where the silt from the mains burn has encroached into the loch and a small jetty existed. The old Beith Mid Road then led up into the town itself.

Natural history

_Kreisel%2C_1989_(Pestle_Puffball)_(2)_crop.jpg)

Plantations are recorded as having existed at Willowyard near Beith from the 19th century and some woodland policies still survive; the southern end had the Lady Mary's planting, but the northern end was devoid of trees.[26] The old industrial sites on the western shore, for the first 0.75 km or so have substantial Willow plantations and there are some groups of older deciduous trees. Beyond the plantations, and continuing round the loch into the very north-east corner, farmland borders the loch. The Bark Mill near Mains House may be responsible for the loss of the oak trees from around the loch. The virtual absence of emergent vegetation is a characteristic of the loch and may be linked to the consolidated substrate.[19]

Castle Semple and Barr Lochs are SSSIs and Kilbirnie Loch is a Scottish Wildlife Trust designated LSNC (Local Site for Nature Conservation) in terms of the Ayrshire Local Biodiversity Action Plan (ALBAP) and in partnership with North Ayrshire Council.[19] High levels of invasive alien waterweed species, Canadian waterweed (Elodea canadensis) and Nuttall’s waterweed (Elodea nuttalli) if left unchecked, will continue to spread and overwhelm other native aquatic plants.[4] The loch's southern end is dominated by large areas of mown grass with mature grown bushes and wood copses. The western shore for the first 0.75 km or so is composed of planted willow with some older deciduous trees; round the loch into the very north-east corner, pastures surround the loch. Along the western part, the ground slopes quite steeply down to the loch. The northern shore itself is level and there are areas of marshy ground. The eastern side of the loch is a narrow strip of reedbed and bogbean grows in sheltered area.[27]

The Mains and Willowyard burns feed the loch from the eastern side and the Black Burn enters from the north-west; both have brought in silt that has created the areas of reedbeds. In addition to the Dubbs Water, a small burn, now piped, drains into the loch at the southern end.

The dominant plant of the waters edge is reed canary grass running from the East round to the South and into the West side. Creeping bent, reed sweet grass and iris are abundant. Common water-crowfoot, chara species, Canadian waterweed, slender spike-rush, perfoliate pondweed and spiked water milfoil are the other main species present.[19]

The diatoms genera Capucina and Asterionella have been recorded, together with blue-green algae, copepods, and some rotifers. Oligochaete worms, snails, freshwater louse, leeches, mayflies, caddisfly larvae, beetles, chironomid larvae, six-spot burnet, green-veined white, common blue, common blue damselfly, are all present.[19]

Rare species

Surveys have identified the following rare species: reed grass (Glyceria maxima); Carex aquatilis; viper's bugloss (Echium vulgare); mare's tail (Hippuris vulgaris); field scabious (Knautia arvensis); spiked water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum); shoreweed (Littorella uniflora); butterfly orchid (Platanthera chlorantha); ivy-leaved crowfoot (Ranunculus hederaceus); weld (Reseda luteola); marsh yellow-cress (Rorippa islandica); bay willow (Salix pentandra); creeping yellow-cress (Rorippa sylvestris);[19] and the relatively rare plant, bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), that grows in sheltered areas on the west bank of the loch.

Activities on the loch

A number of groups use the loch and its surrounds, such as the Kilbirnie Angling Club, Garnock Canoe and Boating Club, Kyle Waterski and Wakeboard Club, the Model Boat Club, Garnock Rugby Club, and the Garnock Valley Model Aircraft Club.

Curling

Before the advent of the ironworks the loch was used for curling and in the 19th century the Paisley Saint Mirren Curling Club records show that they played in matches for Royal Caledonian Curling Club medals at Kilbirnie Loch.[28] The John Bull Magazine records that on 10 January 1850 a match took place on the loch between the Eglinton Kilwinning and Beith Fullwoodhead Clubs with six rinks each and a medal given by the Royal Caledonian Club. The Eglinton team were the victors and the Earl accepted the medal from the umpire, Mr Brown of Broadstone. A large number of spectators were present.[29] A Bonspiel took place at the nearby Barr Loch on 11 January 1850 and attracted huge crowds. The North won for the first time by a majority of 233 shots.[30] The Curling Stone manufacturer, J & W Muir, were at one time based in Beith.[31]

The History of Curling. 1800–1833 records that "In Beith there were then, as there are now, many keen and good curlers who flocked down to Kilbirnie when the 'icy chain' was safely thrown over it."[32]

Angling

Kilbirnie is well known as a fishing loch with big pike and large stocks of roach, plus rainbow and brown trout; boat and bank fishing take place.[33] In 2009 a 30 lb plus pike was caught in the loch.[34] The Kilbirnie Angling Club was founded in 1904 when it fished Kilbirnie Loch and the Plan Dam. In 1934 the club began fishing the Dubbs Water[35] and now leases the Maich Water, Kilbirnie Loch, the Barr Loch, and the Dubbs Water from the Crown Estates.[36] The loch is stocked with rainbow trout.[37]

Circa 1604 it is recorded by Timothy Pont that Loch of Killburney it is ye goodliest frech vatter in all Cuninghame and in 1641 Sir John Crawfurd was ratified as holding the fishing rights.[2] In 1876 it is recorded as being well stored with pike, trout, perch, braize (bream) and eels.[5]

Birds

Late autumn through winter are the times of greatest interest. Mallard, tufted duck, Eurasian coot and mute swan are present throughout the year, but it is towards the end of September before numbers and species begin to increase. Tufted duck, common goldeneye, Eurasian wigeon, Eurasian teal and possibly goosander with sometimes smew and greater scaup. Cormorant are frequent, with grey heron feeding along the banks, and several gull species. It has been noted that waterfowl prefer the northern reaches of the loch. The reedbed habitats are confined and not large enough for marsh specialists, although sedge warbler and reed bunting are probably present.[27]

The willow plantations, other deciduous species and scrub on the western slopes provide cover for great spotted woodpecker, tits, thrushes, finches, and warblers and other passerines. The north-eastern corner and the north shore provide shallower, marshier habitats where waders such as common snipe, common redshank, and curlew. The hawthorn and other tree cover in this area create cover and feeding for finches, tits, and thrushes, which are prey for sparrowhawks. A great grey shrike was seen here in December 2001. Historical records include storm and Leach's petrel, ruff, Atlantic puffin and black-legged kittiwake in the period 1889 to 1915.[27] The loch is a Wetland Birds Survey (WeBS) site and total count results are available on the WeBS site.[38]

Water skiing and Wakeboarding

Kyle Waterski and Wakeboard Club has been active on the loch for over 30 years. The clubhouse is based at the southern end of the loch where there is a car park, slipway and a jetty as well as the club's changing facilities. KWSW is affiliated to both British Waterski & Wakeboard (BWSW) and Waterski and Wakeboard Scotland (WWS). The club has two tournament standard slalom courses and uses a Malibu Response ski boat. It is open for water skiing and wakeboarding from 1 April to 30 September on Wednesday and Friday evenings and also on Saturday and Sunday afternoons.

Garnock Rugby Football Club

Garnock Rugby Club plays on the Lochshore Playing fields, what was part of the old loch area, infilled by the iron and steelworks in the 19th century. The club is an amateur rugby union club and currently plays in the Scottish National League Division 1. The club was formed in 1972 as the result of a merger of the Old Spierians and Dalry High School FP clubs.[39] This was a response to the amalgamation of feeder schools Spier's and Dalry High (along with Kilbirnie Central and Beith Academy) to form Garnock Academy, which happened around the same time. The Old Spierians club had been founded in the early years of the 20th century and joined the Scottish Rugby Union in 1911.

- Handkea exipuliformis

The Pestle puffball fungus (Handkea exipuliformis) grows at the edge of the mainly birch scrub area. This large puffball fungus releases its spores by the decay of the head portion, leaving a pestle-like stem that persists through to the following summer.

Water quality

The loch has had spoil, effluent and other pollutants discharged into it when the Glengarnock Iron and then Steel Works were operational; the remaining slag in the loch is relatively rich in phosphates which exacerbates the pollution problems. In the 1990s the loch become eutrophic as a result of high levels of nutrient input which has sometimes resulted in algal blooms in the summer, counteracted by bales of barley straw. These algal blooms can be dangerous to both humans and dogs. The source of this input has not been clearly tracked down, however a reedbed may be established to act as a filtration system. The loch is rather poor in terms of invertebrate faunal diversity under its present conditions, not helped by the invasive pondweeds, such as Canadian pondweed.[40]

Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park Authority

Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park Authority are not directly involved in the management of Kilbirnie Loch, it does however lie within the regional parks extended boundary. The park authority has in the past initiated discussions with a number of partners including Scottish Natural Heritage, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), RSPB, etc. with 'A Shared Vision' for the 'Three Lochs'. These partners continue to develop options for the potential future management of this important wetland system.[4]

The Willowyard estate

On the east side of the loch lie the ancient lands of Willowyard, locally pronounced 'Williyard', and the various Mains dwellings associated with it. These lands were passed to Helen, daughter of Robert Lord Boyd, in her pure, spotless, and inviolate virginity and were held by her for life, the feu for the property passing to the abbot and convent of Kilwinning.[41] Blaeu's map of Timothy Pont's survey marks the property as 'Williezeards'. In 1559 Hugh Montgomery of Hessilhead held the lands of old extent of Williyard, in the parish of Beith and regality of Kilwinning. The lands became the property of the Hon. Francis Montgomerie of Giffin and then passed to his nephew, Alexander, 9th Earl of Eglinton. in 1723 Mr William Simson or Simpson obtained the property from the Earl.[42] Mr Simpson was said to be a man of expensive tastes and his son William was forced in 1772 to sell the estate to Mr John Ker of London.[43] By 1777 Mr Ker had sold the property to Mr John Neale of Edinburgh. In 1804 John Neale sold the property to Mr Robert Steel of Port Glasgow and John and Robert Duncan are recorded as tenants.[43] By 1833 William Wilson (son of Janet Simson) had purchased Willowyard and his nephew, Alexander Shedden of Morishill later inherited.[42]

The surviving Willowyard House dates from 1727 in the form of 7271[44] is for some unrecorded reason carved on the exterior of the house. Circa 1750 a William Simson is recorded as the owner. By the end of the 18th century Willowyards was a well established farmstead and the Edinburgh Advertiser describes it as: consisting of about 175 English acres of arable land, well enclosed and subdivided into fifteen fields, and let by one lease to three substantial tenants for 19 years at £130 per annum. Upon this property there is a good house, and garden stocked with fruit trees, a malt mill and an elegant court of offices newly erected. A valuable flag and stone quarry has been opened in the ground and it is believed there are both coal and limestone in it. There are about ten acres of wood and a good deal of timber on this farm; and thriving belts of planting surround the greatest part of it.[45]

In 1820 Willowyard is recorded as being an estate of 120 acres, well planted up by the owner with belts of plantings and the fine house situated in full view of the loch. The estate sits on whinstone and a small quarry nearby became an ornamental lake. In 1820 John Neil Esq of Edinburgh was the owner,[46] however by 1822 the owner of Willowyard is recorded as being Robert Steele, a Port Glasgow ironmaster and the lands were assessed as the 14th most valuable in the parish at £114 per year valued rent. The 1827 map by Aitken marks the estate as being the property of Robert Steel Esq.[47] In the New Statistical Account, William Wilson, a maternal descendant of previous owners purchased the estate in 1832[48] and in 1839 Alexander Shedden is noted as the owner.[45]

The Willowyard Industrial Estate is situated between Kilbirnie loch and the town of Beith. A large whisky bond is located in the area with a number of large storage buildings and Willowyard House still stands, converted into offices serving a chemicals company.[49] The rubble walls of the building were harled and the window and angle margins left as exposed dressed stone; the roof was thatched originally. The main railway line from Ayr to Glasgow runs below the industrial estate and forms the eastern margin of the loch in places.

Mains

The properties named 'Mains' became divided up into 'Mains-Neil', 'Mains-Houston', and 'Mains-Marshal'. Robertson records that Mains-Hamilton was recently (1820) converted into a good looking house by Mr. Dun, however it passed to a Mr. Houston.[46] A farmhouse is shown marked as Mains Hamilton on the OS map of 1856 together with an L-plan outbuilding, which may now form part of the former coachhouse at 'The Meadows' on Arran Crescent. The farmhouse was demolished and the villa built on the site, perhaps utilising the existing whinstone.[50] Blaeu's map of Timothy Pont's survey of circa 1600 marks the properties of Mains Mure, Mainshill, and Mains neil, with Mains Mure as a castleated tower house.

The 1911 OS map refers to Mains Lodge as 'Muir Lodge' after William Muir who built Mains House. The Muir family owned the Bath Lane Tannery, near the Beith Health centre of today (2011) and built the Bark Mill. William Muir of Mains joined John Muir and Sons, Tanners, Curriers, and Fancy Leather Manufacturers as a partner in 1846.[51] Laigh Mains, also demolished, was the home farm of Mains House. Dr McCusker, a GP based in Glasgow, owned Mains House at the time of WW2, followed by Mr Dewar, prior to its purchase and demolition which resulted from the establishment of Whisky Bonds here by Ballantyne Whisky Company in 1968, following the disaster of the Cheapside Street Whisky Bond Fire. There were engraved stones with the initials of Mr and Mrs Muir on the Mains House and these were saved when the house was demolished circa 1975 and now form part of a garden within the grounds of the bonded area. Davis records that the original single storey house of 1764 with its attic were used as a service wing to the crow stepped house had the appearance of a double version of the lodge house.[52]

Mid Road used to cross the Bath Burn by a ford near Mains House and then ran up to the town; the road has now been abandoned and is only used by intrepid walkers.

Bark Mill

A Bark Mill, most likely built by the Muirs of Mains House, is marked on OS maps, powered by the combined Mains and Bath Burns with mill ponds indicated. The mill produced ground bark for use in the Beith tanneries using bark from the old oak trees that forested the loch side. Later the mill became a furniture factory run by Matthew Pollock who applied the use of machinery to help with the manufacture of furniture in 1858. This site was one mile from the Beith town centre. The Glasgow & South Western Railway Company constructed a siding, known as 'Muir's siding' for the convenience of transporting the finished products, etc. However the site was isolated and inconvenient for the workers and was eventually sold to Robert Balfour, who later built a new factory near Beith Town Station, the West of Scotland Cabinet Works.[53][54] The Muirs had been tanners for many generations and around 1791 John Muir and Sons, Tanners, Curriers, and Fancy Leather Manufacturers had become established at the Bath Lane works. William Muir of Mains joined as a partner in 1846.[51]

Micro-history

An early Bronze Age flanged axehead was found near East Kerse in 2004 by a metal detectorist and is now in the Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow. The axehead belongs to the so-called Bandon type with a long, straight-sided body, raised edges or low flanges and widely expanded blades. The find is associated at this site with several other finds of metalwork of the later Early Bronze Age.[55]

One of the buildings at the Kerse Bridge was the old 'Kirk's Railway Inn' serving the railway station that once stood across the road from it. Mrs Kirk managed the Railway Inn at the turn of the 20th century Alexander Kirk spent his boyhood years there, attended Spier's school and served in France from 1917, graduated in medicine at Glasgow university and spent his professional life in England. A small pier existed at the north end of the loch in recent times.

Much of the successful drainage works, especially of the Barr Loch, were carried out by Dutch immigrants who introduced the technology from their homeland; Dutch surnames present in the area to this day reflect this immigration. In around 1691 the Rev Patrick Warner likewise purchased and drained much of the Irving Loch or Trindlemoss, later called Scott's Loch, after returning from exile in Holland.[56]

The Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald recorded that in 1904–05 a model yacht race under the auspices of Townhead Model Yacht Club on Kilbirnie Loch the result was: 1, John Martin, jun (Thistle); 2, James Martin (Swift); 3, John Martin (Helena); 4, William McCosh (Reliance)); 5, William Taylor (Genesta); 6, John Taylor (Bona); 7, Robert Taylor (Rover); 8, Robert Martin (Fairlie).[57]

A possible relic of the smuggling days of Beith is the Ley tunnel that is said to run from the site of the Grace Church on Eglinton Street to Kilbirnie Loch.[58]

A geocache is located on the lochside. Kilbirnie Loch is said to be the only Scottish loch to have its main exit at the same end as the source river.

Scottish Enterprise owns much of the former steelworks site, tree plantations now cover areas of former industrial activity.

The Earl of Eglinton had proposed building a canal from Ardrossan to Glasgow which would have run close by to Kilbirnie Loch.[59]

The North Ayrshire Council Ranger Service regularly patrols the loch and work with the Kilbirnie Loch Management Group to licence boats using the loch, monitor fishing, canoeing, sailing, and power boat use. The use of the loch is regulated by Scottish Countryside Access legislation.

Duck Beith

References

Notes;

- UK Lakes Retrieved : 2011-04-05

- Dobie, p. 314

- Dobie, p. 315

- Scottish Natural Heritage Retrieved : 2010-10-24

- Douglas, p. 107

- AWAS (1880), p. 24

- Farewell to Feudalism Retrieved : 2010-10-13

- Blaeu Map Retrieved : 2010-12-07

- Scots Dictionary Retrieved : 2010-10-21

- Old Roads of Scotland Retrieved : 2011-02-06

- Loch Owners Archived 16 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Blaeu's Map Retrieved : 2010-10-20

- West section Armstrong's map Retrieved : 2010-10-30

- Dobie, p. 316

- Kinninburgh, p. 114

- Strawhorn, p. 392

- Campbell, p. 198

- Reid (2001), pp. 13–15

- Paul, Site 69

- AWAS (1880), p. 25

- Kinniburgh, p. 113

- RCAHMS Retrieved : 2010-10-10]

- RCAHMS Retrieved : 2010-10-10]

- Routes to Ride Retrieved : 2010-1—24

- Routes to Ride Retrieved : 2010-1—24

- Dobie, pp. 314–315

- Birding Sites Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Paisley St. Mirren Curling Club. Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Bellman, p. 2

- Murray, pp. 98 – 101.

- Curling History. Retrieved : 2010-10-13

- History of Curling. Retrieved : 2010-10-10.

- Fishing at Kilbirnie Loch Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Flyfishing News Archived 12 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-10-24

- Kinninburgh, p. 93

- Kilbirnie Angling Club (2010)

- Anglers Rendezvous Retrieved 2010-10-24

- WeBS site Retrieved : 2010-10-24.

- Garnock Rugby Club – Club History Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Ayrshire Birding Retrieved : 2010-10-24

- AWAS (1882), p. 184

- Dobie (1896), p. 173

- Dobie (1896), p. 172

- Dobie (1896), p. 174

- British Listed Buildings Retrieved : 2011-01-16

- Robertson, p. 275

- Aitken

- The New Statistical Account

- Love (2003), p. 84

- British Listed Buildings

- Reid, p. 12

- Davis, p. 322

- S1 Beith Archived 27 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2011-01-15

- History of the Furniture Making Industry in Beith Archived 14 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2011-01-15

- RCAHMS Retrieved : 2010-11-23

- Strawhorn, p. 60

- Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Beith Online Retrieved : 2010-10-10

- Love (2003), p. 73

Sources;

- Aitken, Robert (1827). Map of Beith Parish.

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to the counties of Ayrshire & Wigtown. Edinburgh : Ayr Wig Arch Soc. 1880.

- Archaeological & Historical Collections relating to the counties of Ayrshire & Wigtown. Edinburgh : Ayr Wig Arch Soc. 1882.

- The Bellman. Beith Cultural and Heritage Society. Issue 12. January 2011.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0.

- Davis, Michael C. (1991). The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire. Ardrishaig : Spindrift Press.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Dobie, James (1896). Memoir of William Wilson of Crummock. Edinburgh : James Dobie.

- Douglas, William Scott (1874). In Ayrshire. Kilmarnock : McKie & Drennan.

- Kinniburgh, Moira & Burke, Fiona (1995). Kilbirnie & Glengarnock. Shared Memories. Kilbirnie Library. ISBN 1-897998-01-5.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Murray, W. H. (1981). The Curling Companion. Glasgow : Richard Drew. ISBN 0-904002-80-2.

- Paul, L. & Sargent, J. (1983). Wildlife in Cunninghame. Edinburgh : SWT, NCC, MSC, CDC

- Reid, Donald (2001). In the Valley of the Garnock (Beith, Dalry & Kilbirnie. Beith : DoE. ISBN 0-9522720-5-9.

- Reid, Donald L. (2011). Voices & Images of Yesterday and Today. Beith, Barrmill, and Gateside. Precious Memories. Irvine : Kestrel Press. ISBN 978-0-9566343-1-3.

- Robertson, George (1820). Topographical Description of Ayrshire : Cunninghame. Irvine : Cunninghame Press.

- Strawhorn, John (1985). The History of Irvine. Royal Burgh and Town. Edinburgh : John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-140-1.

- Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire. Edinburgh : Oliver & Boyd.

- The New Statistical Account of Scotland. 1845. Vol. 5. Ayr – Bute. Edinburgh : Blackwood & Sons.

External links

- Commentary and video on the Bark Mill at Beith

- Kilbirnie Loch on YouTube

- Video of Kilbirnie Loch – Southern end

- Video of Kilbirnie Loch – Northern end

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kilbirnie Loch. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maich Water. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mains House. |