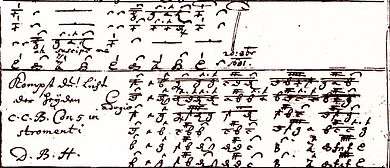

Keyboard tablature

A keyboard tablature is a form of musical notation for keyboard instruments. Widely used is some parts of Europe from the 15th century, it co-existed with, and was eventually replaced by modern staff notation in the 18th century. The defining characteristic of the notation type is the use of letters[lower-alpha 1] to indicate pitch as well as other symbols for rhythm and other required precisions.

Historical details

The earliest extant music manuscripts written in tablature notation date from the first half of the 15th century, with the oldest example, a German manuscript dating from 1432, containing the earliest known setting of a partial organ mass as well as a piece based on a cantus firmus.[1] These manuscripts used letters (the same as today) to identify pitch, with the upper voice typically written in mensural notation.[2] This style was also present in other German-speaking areas, such as Austria.[3] These manuscripts contain valuable information as to the evolution of the music from the period,[4] with extensive evidence of the influence of vocal, and later dance music, on early instrumental music.[5] This practice which could still be seen in collections from the 16th century[6] eventually led to the full fledged Baroque dance suites of later centuries.[7] Tablature was also featured in some early printed music books, with an example dating from 1512.[8]

Differences with later notation include that the upper voice would eventually come to be written using letters as well,[3] a practice which was popularised in the latter part of the 16th century,[9] and contemporary examples of musical notation, such as Samuel Scheidt's Tablatura Nova, may initially have been written in the so-called "new German organ tablature", favored by organists for reading contrapuntal works (instead of open score notation) since the voices were strictly aligned vertically. This style of notation would remain in use in Germany (and neighboring areas, such as modern-day Hungary[10] or Poland[11]) up until the time of Bach,[12] and the music of some composers of the period remains available only in manuscript tablature. format[13][14]

In other countries, such as France, England or Italy, keyboard notation was similar to its modern day form,[15] and while there are isolated examples of tablature from England, there is no evidence that such use was as widespread as in Germany or Spain.[16]

Notation

Footnotes

- Although letters are by far the most common method, numbers are also a possibility. See Colton 2010 for the description of an English example, or Encyclopedia Britannica 2018 for a description of Spanish keyboard tablature.

Citations

- Apel 1937, p. 210.

- Apel 1937, p. 212.

- Crane 1965.

- Apel 1937, p. 213-217.

- Apel 1937, p. 218,229,235-237.

- Apel 1937, p. 226.

- Apel 1937, p. 230.

- Apel 1937, p. 220-222.

- Apel 1937, p. 232-233.

- Papp 2005.

- Baron 1967.

- Boe & Godwin 1974.

- Tuck 1966, p. 123.

- Smith 2009.

- Tuck 1966, p. 122.

- Colton 2010, p. 41-42.

Bibliography

- Apel, Willi (1937), "Early German Keyboard Music", The Musical Quarterly, 23 (2): 210–237, doi:10.1093/mq/xxiii.2.210, ISSN 0027-4631, JSTOR 738677

- Apel, Willi (1961), The notation of polyphonic music, 900-1600 (4th ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Medieval Academy of America

- Baron, John H. (July 1967), "A 17th-Century Keyboard Tablature in Brasov", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 20 (2): 279–285, doi:10.2307/830790, JSTOR 830790

- Benson, Joan (2014), "Exploring the Past: Fifteenth through Seventeenth Centuries", Clavichord for Beginners, Indiana University Press, pp. 68–82, ISBN 9780253011589, JSTOR j.ctt16gzjxk.10

- Boe, John; Godwin, Joscelyn (1974), "Playing from Original Notation", Early Music, 2 (3): 199–201, doi:10.1093/earlyj/2.3.199, ISSN 0306-1078, JSTOR 3125580

- Braatz, Thomas (1 September 2006), "BWV 1121 - Organ Tablature", www.bach-cantatas.com, retrieved 15 May 2019

- Crane, Frederick (July 1965), "15th-Century Keyboard Music in Vienna MS 5094", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 18 (2): 237–243, doi:10.2307/830688, JSTOR 830688

- Colton, Lisa (2010), "A Unique Source of English Tablature from Seventeenth-Century Huddersfield", Music & Letters, 91 (1): 39–50, doi:10.1093/ml/gcp081, ISSN 0027-4224, JSTOR 40539093

- "Tablature", Encyclopedia Britannica, 2018

- Emery, Walter (October 1938), "The Orgelbuchlein: Some Textual Matters: I. Readings of the tablature in 'Christus, der uns selig macht'", The Musical Times, 79 (1148): 770–771, doi:10.2307/923787, JSTOR 923787

- Gaare, Mark (March 1997), "Alternatives to Traditional Notation", Music Educators Journal, 83 (5): 17–23, doi:10.2307/3399003, JSTOR 3399003

- Godwin, Joscelyn (1974), "Playing from Original Notation", Early Music, 2 (1): 15–19, doi:10.1093/earlyj/2.1.15, ISSN 0306-1078, JSTOR 3125877

- Jackson, Roland (July 1971), "[Letter from Roland Jackson]", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 24 (2): 318, doi:10.2307/830503, JSTOR 830503

- Johnston, Gregory S. (1998), "Polyphonic Keyboard Accompaniment in the Early Baroque: An Alternative to Basso Continuo", Early Music, 26 (1): 51–64, doi:10.1093/em/26.1.51, ISSN 0306-1078, JSTOR 3128548

- King, A. Hyatt (1962), "The Organ Tablature of Johann Woltz", The British Museum Quarterly, 25 (3/4): 61–63, doi:10.2307/4422744, JSTOR 4422744

- Nanni, Matteo; Moths, Angelika, "How do tablatures work? - From Ink to Sound", FutureLearn, University of Basel

- Papp, Ágnes (1 August 2005), "Orgeltabulaturen des 17. Jahrhunderts aus Ungarn: Intavolierung, Reduktion, Notationsarten" [Hungarian organ tablatures from the 17th century: Intabulation, reduction, notation types], Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in German), 46 (3): 441–469, doi:10.1556/SMus.46.2005.3-4.9, JSTOR 25164477

- Rifkin, Joshua (April 1969), "[Letter from Joshua Rifkin]", Journal of the American Musicological Society, 22 (1): 142, doi:10.2307/830826, JSTOR 830826

- Smith, David J. (2009), "Early Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Culture at the Court of the Archdukes in Brussels: The Manuscript Kraków, Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Mus. MS 40316", Revue belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap, 63: 67–98, ISSN 0771-6788, JSTOR 25746578

- Tuck, Mary Lynn (1966), "Tablature Notation in the Sixteenth Century", Music Educators Journal, 53 (1): 121–123, doi:10.2307/3390828, ISSN 0027-4321, JSTOR 3390828

- Wollny, Peter; Maul, Micheal (2008), "The Weimar Organ Tablature: Bach's Earliest Autographs" (PDF), Understanding Bach, 3: 67–74

See also

References