Kerry slug

The Kerry slug or Kerry spotted slug (Geomalacus maculosus) is a species of terrestrial, pulmonate, gastropod mollusc. It is a medium-to-large sized, air-breathing land slug in the family of roundback slugs, Arionidae.

| Kerry slug | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo of dorsal view | |

| |

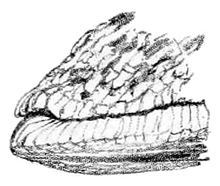

| Drawing of right side view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Heterobranchia |

| Superorder: | Eupulmonata |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Family: | Arionidae |

| Genus: | Geomalacus |

| Subgenus: | Geomalacus |

| Species: | G. maculosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Geomalacus maculosus Allman, 1843[2] | |

| |

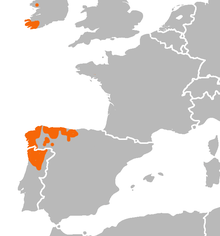

| Distribution map for the species. | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Adult Kerry slugs generally measure 7–8 cm (2.8–3.2 in) in length; they are dark-grey or brown with yellowish spots. The internal anatomy of the slug has some unusual features and some characteristic differences from the genus Arion, also part of Arionidae. The Kerry slug was described in 1843—later than many other relatively large land gastropods present in Ireland and Great Britain—an indication of its restricted distribution and secretive habits.

Although the distribution of this slug species includes south-western Ireland—including County Kerry—the species is more widespread in north-western Spain and central-to-northern Portugal. It is not found in locations between Ireland and Spain. The species appears to require environments that have high humidity, warm summer temperatures and acidic soils with no calcium carbonate. The slug is mostly nocturnal or crepuscular but in Ireland it is active on overcast days. It feeds on lichens, liverworts, mosses and fungi, which grow on boulders and tree trunks.

The Kerry slug is protected by conservation laws in the three countries in which it occurs. It is now known to be less dependent on sensitive, wild habitats than when these laws were introduced. Attempts have been made to establish breeding populations in captivity to ensure the survival of this slug species but these have been only partly successful.

Taxonomy and etymology

The Kerry slug is a gastropod, a class of molluscs that includes all snails and slugs, including terrestrial, freshwater and marine species. The Kerry slug, a member of the order Panpulmonata, is terrestrial; it breathes air with a lung. It is in the clade Stylommatophora, members of which have two sets of retractable tentacles, the upper pair of which have eyes on their tips. Its family is Arionidae, the round-backed slugs. The Kerry slug has no keel on its back, unlike the slugs in the families Limacidae and Milacidae. Many of its anatomical features are shared with species in the genus Arion, which is a more species-rich and widely distributed group of slugs within Arionidae. The Kerry slug is placed in the genus Geomalacus, which means "earth mollusc".

The Kerry slug's scientific name is Geomalacus maculosus, where maculosus means "spotted" from the Latin word macula, a spot.[6] The English-language common name is derived from County Kerry in the south-west of Ireland, where the type specimens that were used for the formal scientific description were collected. In 1842, a Dublin-based naturalist William Andrews (1802–1880) sent specimens he had found at Caragh Lake in County Kerry to the Irish biologist George James Allman. The next year, Allman exhibited them at the Dublin Natural History Society and published a formal description of the new species and genus in the London literary magazine The Athenaeum.[7][2] The full scientific name, including the taxonomic authority, is Geomalacus maculosus Allman, 1843. The synonyms are other binomial names that were given over time to this taxon by authors who were unaware that the specimens they were describing belonged to a species already described by Allman.

The species' binomial name is sometimes written as Geomalacus (Geomalacus) maculosus because the genus Geomalacus contains two subgenera; the nominate subgenus (subgenus of the same name) Geomalacus and a second subgenus Arrudia Pollonera, 1890. The subgenus Geomalacus contains only one species, the Kerry slug; three species comprise Arrudia.[8] The Kerry slug has been included in molecular phylogenetics studies since 2001.[9]

Description

The body length of adult Kerry slugs is 7–8 cm (2.8–3.2 in).[10] These slugs are difficult to measure accurately because of their unusual startle response. Kerry slugs can also elongate themselves within crevices up to 12 cm (4.8 in).[10] Official measurements of this species vary; Kerney et al. (1983)[11] give a range of measurements of 6–9 cm (2.4–3.6 in). The body of a fixed (preserved) adult specimen was 7 cm (2.8 in) long with a mantle length of 3 cm (1.2 in).[10]

The body of the Kerry slug is glossy and is covered on both sides with about 25 longitudinal rows of polygonal granulations. The slugs have two colour morphs, brown and black. In Ireland the black morph occurs in open habitats and the brown morph occurs in woodland; this correlates with the colours of the surroundings, suggesting camouflage. Experiments indicate the dark colouration is induced by exposure to light as the slug develops.[12] There is also variation in banding; on each side of the body there can be two bands: one band just below the summit of the back and the other band further down the side of the body. When these bands are present they usually extend the whole length of the body and are overspread by numerous, ovoid yellow spots that are distributed approximately in five longitudinal zones.[7]

Behind the animal's head is the shield-shaped outer surface of the mantle, which is about a third of the length of the body when the slug is actively crawling and thus extended; when the slug is stationary and contracted, the shield is about half the length of the body. The front of the shield is rounded and its rear is bluntly pointed. The surface texture of this area resembles the underside of undyed leather; it is spotted with pale, buff or light-coloured spots that are similar to those on the body but are more uniformly distributed.[7]

The foot fringe, a band of tissue around the edge of the foot, is not distinctly separated; it is very pale and somewhat expanded and has indistinct lines on it.[7] The sole of the foot is pale grey-yellow and is divided into three indistinct bands; the mid-area is somewhat darker and more transparent than the side bands.[7] There is a caudal mucous pit situated between the foot and the body on the upper surface of the tip of the tail. The pit, which collects extra mucus, is not conspicuous, triangular and opens transversely. The mucous pit often carries a transparent, yellowish ball of mucus.[7]

The Kerry slug's upper tentacles are smoky-black or grey, short and thick with oval ends, and have eye spots at their tips. The genital pore or opening lies behind and below the right eye tentacle.[13] The lower tentacles are pale-grey and translucent.[7] The skin mucus is usually pale yellow and varies in viscosity. The locomotory mucus is tenacious and usually colourless but is sometimes yellow because of mixing with body slime.[7]

Internal anatomy

Shell

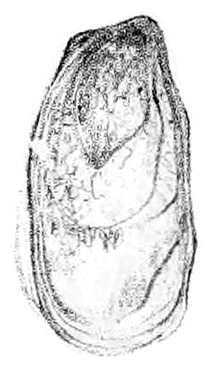

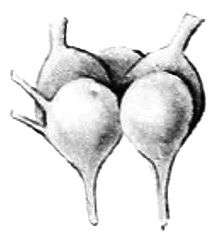

Within the mantle, most land slugs have the remnants of what was in the evolutionary past a larger, external shell. Usually this remnant is either a small, thin, shell-like plate or a collection of calcareous (chalky) granules. The Kerry slug has an internal shell or shell plate that resembles those found in land slugs of the genus Limax; it is ovoid, solid and chalky with a transparent conchiolin (horny) base. The shell plate is usually convex above and concave beneath and has some indistinct, concentric lines of growth. According to Godwin-Austen, the exterior of the shell plate is covered with a thin, transparent protein layer called the periostracum and with the nucleus—the first part to form—situated near the front. In young Kerry slugs the shell is very thin and convex, abruptly cut off behind, and with an extremely thin layer that projects in front and contains minute granules.[7]

Authors have differed in their depictions of the Kerry slug's shell plate but they are consistent in showing it as a solid plate.

The internal shell as drawn by Taylor in 1907 |

The internal shell as drawn by Godwin-Austen in 1882  Photograph of internal shell of G. maculosus (dorsal view). |

Various organ systems

The circulatory and excretory systems of the Kerry slug are closely related; the heart is surrounded by the triangular kidney, which has a lamellate (layered) structure and two ureters. In this species, the ventricle of the heart is directed towards, and is very close to, the anal and respiratory openings. The ventricle of the heart is further away and further back than it is in species of the related genus Arion, the type-genus of the family Arionidae.[7]

The gland above the foot, the suprapedal gland, is deeply imbedded in the tissues and reaches far back. The cephalic (head) gland known as Semper's organ is well developed and shows as two strong, flattened lobes. The salivary and digestive glands are the same as those found in Arion species but the vestigial osphradium (kidney-like structure) within the mantle chamber is more distinct than it is in Arion species.[7]

Muscles

In the Kerry slug, the cephalic retractors (muscles for pulling in the head) are very similar to those in Arion species. The right and left tentacular muscles, which pull in all four of the tentacles, divide early for the upper and lower tentacles but only the muscles of the ommatophores—the two upper tentacles, which have eye spots—are darkly pigmented. The right and left muscles that pull in the eye-spot tentacles are attached at the base to the back edge of the mantle on the right and left respectively. The pharyngeal (throat) retractor muscle is furcate (split) where it attaches to the back of the buccal bulb (mouth bulb); its other end is anchored on the right side of the body, just behind the site of attachment of the right tentacular muscle.[7]

Reproductive system

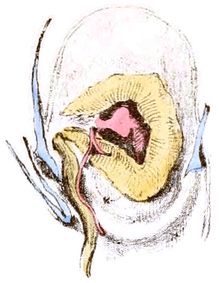

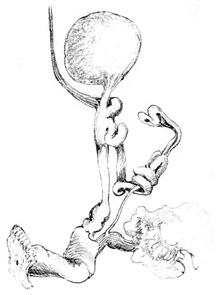

The Kerry slug is a hermaphrodite, as are all pulmonates. Various authors have depicted its reproductive system: Godwin-Austen (1882),[14] Sharff (1891),[13] Simroth (1891, 1894),[4][15] Taylor (1907),[7] Germain (1930),[16] Quick (1960)[17] and Platts & Speight (1988).[18] Platts & Speight [18] considered the depiction by Godwin-Austen (1882)[14] to be the most accurate of those by earlier authors; others depicted the atrium too short.

The ovotestis—a combination of ovary and testis—is small, compact and darkly pigmented. The hermaphroditic duct, where sperm is stored, is long and convoluted, and ends in a small, spherical, seminal vesicle. The albumen gland, which produces albumen for the eggs, is elongated and shaped like a tongue. The ovispermatoduct, along which both eggs and sperm pass, is greatly twisted. This turns into the free oviduct after the vas deferens carrying the sperm branches off. The free oviduct is long and consistently thin.[7] It opens into the atrium near the genital pore, where the muscular atrium is greatly but irregularly enlarged and connected by muscle fibres to the oviduct.[7]

The vas deferens is long, complexly twisted, and rolled in a bundle. The bursa copulatrix for digesting spermatophore and sperm—earlier literature refers to this as the spermatheca—is globular and has a short bursa duct. There is a long retractor muscle from the bursa duct, its other end is anchored near the tail of the slug at the midline. The vas deferens and the bursa duct open nearly together into the far extremity of the atrium, the duct into which both the male and the female systems open and which connects to the outside via the genital pore. A special feature of the genus Geomalacus, is the extremely elongated atrium.[18] The elongated portion of the atrium further from the genital pore than the insertion of the oviduct is termed the atrial diverticulum. In Geomalacus, the penis and its penial retractor muscle have been lost. The atrial diverticulum has been proposed to be the functional equivalent, homoplasy) of a penis, acting as a copulatory organ.[19] It is presumed that the bursa retractor muscle retracts the atrial diverticulum.[19]

In Geomalacus maculosus, the atrial diverticulum is longer than the bursa duct; this situation is reversed in Geomalacus anguiformis.[18]

Godwin-Austen[20] noted that the part of the atrium just inside the genital pore—he called this region the "vagina"—has "a curious arrangement" of flattened folds. The central part, situated close to the genital pore, has a pointed end. He compared this to the calcareous darts in other genera; on the preceding pages he had described such structures in the Asian slug genus Anadenus).

The reproductive system illustrated by Godwin-Austen (1882).[14] The large mass on the right is albumen gland, the mass on the lower part right is the ovotestis, the oval shape at the left is the bursa copulatrix. Mantle edge and atrium is at the top. |

Drawing of "male part" of the reproductive system. From lower left to upper left: genital pore, atrium, atrial diverticulum, bursa duct, bursa retractor muscle, bursa copulatrix. On the top right: epiphallus. Center: vas deferens. Lower right: free oviduct, spermoviduct. |

Apparatus for feeding

Radula

The radula, which is located inside the mouth, is a feeding structure that is unique to molluscs. Typically, it is a small, strong, ribbon-like structure that bears numerous complex rows of tiny teeth across it.

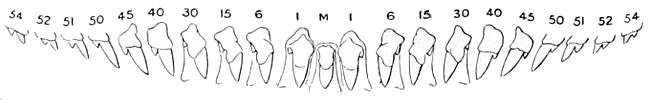

In the Kerry slug, the radula is 8 mm (5/16 in) long and 2 mm (1/16 in) wide, and has 240 slightly curved, transverse rows of denticles; tiny teeth. Each row of teeth is composed of one median tooth and 10 lateral and marginal teeth on each side. The median teeth are small, have one cusp and are slightly shouldered. The lateral teeth have two cusps. The admedian (next to the middle) teeth are larger than the median row and the mesocone—an extra protrusion in the middle of the tooth—is well developed. The only difference between the lateral and marginal series is that the ectocone (extra little side protrusion) present on the admedian teeth recedes in position and slightly diminishes in size in the succeeding teeth up to about the 20th row on the radula. In the marginal series, however, the ectocone gradually grows in size and importance as the margin is approached while the mesocone becomes almost correspondingly diminished. The outermost teeth show a more embryonic character.[7]

Jaw

The jaw of the Kerry slug is about 1 mm (1/32 in) from side to side and is distinctly arched from front to rear, crescent-shaped and very wide with broad and slightly rounded ends. The jaw is solid, dark-brown and has about 10 broad flat ribs in the middle part of the jaw. These ribs are absent or scarcely discernible on the side areas. Where the ribs meet the upper edge, they sometimes form crenulations ( a scalloped effect) and may also produce the same effect on the lower edge of the jaw. In other individuals, the ribs extend across the jaw, making both the upper and the cutting edges of the jaw clearly toothed in outline.[7]

In the Kerry slug, as in all species within the family Arionidae, the alimentary canal of the digestive system forms two loops.[21]

Distribution

The Kerry slug has a discontinuous or disjunct distribution; it is found only in Ireland—mostly the south-western corner—[22] in north-western Spain, and central-to-northern Portugal.[23] It was once reported as occurring in France but this has not been confirmed and that record is considered suspect.[24] Similar distribution patterns have been observed in other species of animals and plants. This particular disjunct distribution in Iberia and Ireland with no intermediate localities is known as a "Lusitanian distribution".

There has been speculation that G. maculosus was introduced to Ireland from Iberia by prehistoric humans; a similar introduction appears to have happened with the Eurasian pygmy shrew.[25][26] In support of such an origin or of a more recent human-mediated introduction, the genetic diversity of the Kerry slug in Ireland was found to be greatly reduced compared with that of the Iberian populations.[27]

Ireland

Within Ireland, the Kerry slug is known to occur in areas with sandstone geology in West Cork and County Kerry,[24] an area of around 5,800 km2 (2,200 sq mi).[10] In 2010, a previously unknown population was recorded further north in County Galway.[22]

Protected sites

A significant proportion of the Kerry slug's range in Ireland is protected by being included in Special Areas of Conservation (SACs). In response to European environmental legislation, Ireland has designated seven SACs with the slug named as a "selection feature": Glengarriff Harbour and Woodland; Caha Mountains; Sheep's Head; Killarney National Park, MacGillycuddy's Reeks and Caragh River Catchment; Lough Yganavan and Lough Nambrackdarrig; Cloonee and Inchiquin Loughs, Uragh Wood and Blackwater River (Kerry).[28] In addition, St. Gobnet's Wood SAC (which was designated in relation to other selection criteria) was expanded in 2008 to protect Cascade Wood, a small area of woodland which is inhabited by the slug.[29] The species has also been recorded at other SACs where it is not a selection feature, for example in Derryclogher Bog, County Cork.[30]

Iberia: Spain and Portugal

Despite its first discovery at Caragh Lake and its English common name of Kerry slug, Ireland is at the periphery of this slug species' distribution; in terms of genetic diversity the distribution is centred on the north-western parts of the Iberian peninsula.[27][31] The Kerry slug has been known in northern Spain since 1868 and in northern Portugal since 1873.[24]

Portugal

The southernmost locality where this species is found is the mountain range Serra da Estrela in Portugal. It is also found in the provinces Beira Alta, Douro Litoral, Minho, Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro and in the Peneda-Gerês National Park.[23][32]

Spain

In Spain, the distribution of this species includes coastal locations in Galicia and extends through the Cantabrian Mountains as far east as Mount Ganekogorta in the Basque Country. These localities fall within the boundaries of various autonomous communities: Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León (provinces of León, Palencia and Zamora), and the Basque Country provinces of Biscay and Álava.[23][32] There have been unconfirmed findings of this slug from Navarra.[32]

Protected sites

Natura 2000 sites for this species in Spain include 48 localities (listed below, grouped by region). As at 2017, some of these sites have yet to be designated as Special Areas of Conservation:[28]

- Asturias

- Cantabria

- Camesa river; Liebana (Special Area of Conservation; Liébana (Special Protection Area); "Upper valleys of the Nansa and Saja and Alto Campoo");

- Castile and León

- Hoces de Vegacervera; Lake Sanabria and its vicinities; Montes Aquilanos (Site of Community Importance); Montes Aquilanos y Sierra de Teleno (SPA);

- Natural Park of Fuentes Carrionas and Fuente Cobre-Montaña Palentina (SAC); Sierra de la Cabrera (SCI partially overlapping with a SPA of the same name).

- Galicia

- A Marronda; Anllóns river; Baixa Limia; Baixa Limia - Serra do Xurés; Baixo Miño; Bidueiral de Montederramo; Carballido, a yew wood in A Fonsagrada; Carnota – Monte Pindo; Cíes Islands; Costa Ártabra; Costa da Morte—Costa da Morte and Costa da Morte (Northern); Cruzul-Agüeira; Encoro de Abegondo-Cecebre; Eo river is included among the Galician sites although the estuary forms the boundary with Asturias; Costa de Ferrolterra-Valdoviño; Fragas do Eume; Macizo Central, Ourense (province); Monte Aloia; Monte Maior; Negueira; Pena Trevinca; Pena Veidosa; Serra do Candán; Serra do Cando; Serra do Xistral; Sil river canyon; Sobreirais do Arnego; Tambre - two areas, the river and its estuary; Támega river; Ulla-Deza river system

- More than one region

- Ancares - This district is divided between Galicia and Castile and León. Sierra de los Ancares is a mountain range that forms the boundary between the two autonomous communities and gives its name to a Natura 2000 site in the province of León.[33] On the Galician side of the sierra are two relevant sites—Ancares (protected under the Birds Directive) and Ancares-Courel (protected under the Habitats Directive).[34][35]

- Picos de Europa - This mountain range is divided between three autonomous communities. The three sites listed are Picos de Europa, Picos de Europa (Asturias), and Picos de Europa en Castilla y León, all of which include protected areas in the Picos de Europa National Park and in a regional park in Castile and Leon that is also called Picos de Europa.

Behaviour

The Kerry slug is primarily nocturnal. During daylight hours, the slug usually hides in crevices of rocks and under loose bark on trees.[36] In Iberia, juvenile Kerry slugs become active during twilight and adults become active at night, especially on rainy or very humid nights.[10][23][36] Because Ireland is much further north and has a considerably cooler, wetter and more humid climate, the Kerry slug is sometimes active there in the daytime if the weather is humid and overcast.[18]

The species has in unusual defensive behaviour; whereas most land slugs retract the head and contract the body but stay firmly attached to the substrate when they are attacked or threatened, the Kerry slug retracts its head, lets go of the substrate and rolls itself into a ball-like shape.[10] This is behaviour is unique among species in Arionidae[11] and among slugs in Ireland.[10]

Ecology

Habitat

It was once thought that Geomalacus maculosus lives only in wild habitats.[24] In the Iberian Peninsula, it occurs on tree trunks in oak (Quercus) and chestnut (Castanea) forest but it is easiest to find in synanthropic habitats such as rocky walls in oak or chestnut orchards, in ruins, near houses, churches and cemeteries.[37] In Ireland, it also occurs in upland conifer plantations and areas of clear-fell.[38] The Kerry slug is not considered an agricultural pest,[24] unlike some other slugs in the family Arionidae.

In Ireland, the Kerry slug occurs in woodland with oak trees, oligotrophic open moorland, blanket bogs and lake shores, especially if boulders covered with lichens and mosses are present in these habitats.[24][38] Although there was a geographical association with sandstone areas, the new locality in Galway is on granite.[38] In Iberia it usually occurs in granite mountains,[36] and on slates, quartzite, schists, gneiss and serpentine.[39] The best predictor of its occurrence is high rainfall and high summer temperatures.[37]

Feeding

The food of Geomalacus maculosus includes lichens, liverworts, mosses, fungi (Fistulina hepatica)[18] and bacteria that grow on boulders and on tree trunks.[23][24][40] In captivity, the Kerry slug has been fed on porridge, bread, dandelion leaves, lichen Cladonia fimbriata, carrot, cabbage, cucumber and lettuce.[10][7] It can be carnivorous in captivity; there are records of it consuming the snail Vitrina pellucida.[7]

Life cycle

The Kerry slug mates in head-to-head position with partners' genital openings facing each other.[18] The sexual organs, called atria—singular:atrium—are funnel-shaped with fluted edges after mating.[18] As in Arion, sperm is transferred in a spermatophore.[41] In the wild, eggs are laid between July and October,[10] and from February to October in captivity.[40] Self-fertilisation is also possible in this species.[10] Eggs are laid in clusters of 18 to 30,[10] and are held together by a film of mucus. The egg masses are about 3.5 cm × 2 cm (1.38 by 0.79 inches).[40]

The eggs are very large compared with the size of the animal. The largest eggs are more elongate, being 8.5 mm × 4.25 mm (0.335 by 0.167 inches); the smallest are more ovoid and are 6 mm × 3 mm (0.24 in × 0.12 in). All are semi-translucent, milky-white or opalescent when fresh,[42] although some of the larger and more elongate eggs have a semi-transparent area at the smaller end. The opalescent lustre disappears in a few days and the eggs turn yellowish and later brown[7] or black.[40]

The young appear to hatch in six[40] to eight weeks, at this stage the spots on the body are barely present. The lateral bands are distinct and black, and are more conspicuous than they are in mature slugs of this species. In juveniles the shield shows lyre-shaped markings, as is the case in slugs of the genus Arion. These lyre-shaped markings become indistinct as the slugs grow larger. The Kerry slug probably overwinters in the sexually immature stage.[7] The bodies of preserved juvenile specimens are up to 3 cm (1.2 in) long with a mantle length of 10 mm (0.39 in).[10] Juveniles reach maturity in two years, at a length about 2.6 cm (1.0 in).[10][40] In the wild, the Kerry slug can live for up to seven years[10] but in captivity, the lifespan rarely exceeds three years.[40] In numerous localities in Spain, very few individuals of the species were observed at any one time.[36]

Until 2014, the natural enemies of Geomalacus maculosus were not known.[43] The Kerry slug's predators include larvae of the third instar of the fly Tetanocera elata.[43]

Threats

The most serious threat to the Kerry slug is probably the modification of habitat, which reduces its lichen and moss food sources.[24] This can lead to the local disappearance of the species, which was documented in Spain.[24][36] Other threats include intensification of land use, land reclamation, use of pesticides, overgrazing by sheep, removal of shrubs, tourism, general development pressures, planting of conifer plantations, the spread of invasive plants such as Rhododendron ponticum and habitat fragmentation[24][44] (see also Moorkens 2006).

Other potential dangers to the species are climate change and air pollution, which negatively affect the lichens eaten by the Kerry slug. Climate change will probably affect the Iberian populations more acutely because the climate there is already hot and dry relative to that of Ireland, which is generally cool and damp.[24]

Conservation measures

International protection

Because of its perceived rarity and its restricted distribution, the Kerry slug is protected under the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention), EIS Bern Invertebrates Project. This decision was backed by studies of its distribution and ecology in Ireland,[18] which concluded that evidence of a decline in Iberia and uncertainty over its status in Ireland tended to support its inclusion in the Convention. Since 2006, Geomalacus maculosus has been considered a least concern species in the IUCN Red List;[1] between 1994 and 2006, however, the slug was rated as vulnerable.[24]

Geomalacus maculosus is also protected by the European Union's Habitats Directive and has been listed as an Annex II and Annex IV species since 1992.[45] The principal mechanisms used by the Directive to protect habitats and species are the creation of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and the protection of species independently of their habitats by other means. Seven SACs have been designated for this species in Ireland and 49 SCIs in Spain.[28] Threats to the Kerry slug will probably be greatest in areas not specifically protected as SACs. The Habitats Directive protects the Kerry slug outside the SACs by Article 12 (1), which obliges European Union member states to:

- establish ‘a system of strict protection’ for listed species

- prohibit deliberate capture or killing

- prohibit ‘deliberate disturbance … particularly during the period of breeding, rearing, hibernation and migration’

- prohibit ‘deliberate destruction or taking of eggs from the wild’

- prohibit the deliberate or non-deliberate ‘deterioration or destruction of breeding sites or resting places’.

Protection in Iberia

Conservation status reports from Portugal and Spain were not yet available in August 2009.[46] Its conservation status in Spain for the IUCN criteria is vulnerable.[32]

Protection in Ireland

In 1988, Platts and Speight noted that only three of the Irish sites where the slug occurred were protected; Glengariff Forest, West Cork; Uragh Wood Nature Reserve, South Kerry; and Killarney National Park, North Kerry. They concluded that the species could not be adequately safeguarded with only three sites and supported its inclusion in the Bern list, to which the Irish government is a signatory.[18] The Habitats Directive was transposed into Irish law by:

- The EC (Natural Habitats) Regulations 1997.[47] This was the principal legislation transposing the Habitats Directive and upgraded the protection of the Kerry slug's habitat by the designation of Special Areas of Conservation.

- Adapting existing legislation. The Kerry slug has been protected since 1990 under the Irish Wildlife Act of 1976; it was added to the list of protected species by Statutory Instrument 112/1990, and was the only gastropod so protected.[45][48] The treatment of the Kerry slug has been cited in the media as an example of hyperprotectionism, specifically, in the context of delays in the construction of a proposed by-pass in County Cork.[49] The Wildlife Act does not protect the slug from indirect damage but only from wilful direct damage such as collecting.

The Irish National Parks and Wildlife Service published a Species Action Plan for the Kerry slug in January 2008.[24][50] Efforts were made to protect the slug from indirect damage, for instance from commercial forestry.[51] Following a legal challenge to Ireland's transposition and implementation of the Habitats Directive, however, the Action Plan was superseded in May 2010 by a Threat Response Plan that addressed problems that arose when the European Court of Justice held that Ireland was not protecting the Kerry slug with the strictness the directive required for a species listed in annex 4.[30][52]

Monitoring

In a report to the European Commission covering 1988–2007, the conservation status of the species in Ireland was declared "favourable (FV)" in all evaluated criteria; range, population, habitat and future prospects.[10][44] The validity of this assessment, however, was put into question by the European Court of Justice ruling that held that Ireland was not monitoring the slug properly.[25]

The need to improve monitoring was discussed by the NPWS Threat Response Plan of 2010, which recognised that population statistics were still deficient, particularly outside the SACs. As the Threat Response Plan noted, species monitoring is a process in which distribution and status of the subject are evaluated systematically over time. Under this definition, no monitoring of the Kerry Slug had been undertaken in Ireland as of May 2010.[30] The Kerry Slug Survey of Ireland, a collaboration between the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the Applied Ecology Unit at the National University of Ireland, Galway, researched a "suitable monitoring protocol" for the species.[29][53] The Kerry Slug Survey's investigations resulted in the publication of a guide to the population dynamics of the Kerry slug, which was published as part of the Irish Wildlife Manual series in 2011.[54]

Captive breeding

Since 1990, the Kerry slug has been successfully bred in captivity. The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, a British conservation organisation, operates a captive breeding programme in terraria at its "Endangered Species Breeding Unit". The project is located at the Martin Mere Wetland Centre in Lancashire, England.[40] During the 1990s, slugs from the breeding programme were given out to a number of zoos and individuals to set up their own breeding programmes but very few of those breeding groups survived.[40]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from Taylor (1907).[7]

- "Geomalacus maculosus". 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 18 July 2007. External link in

|work=(help) - Allman, G. J. (1843). "On a new genus of terrestrial gasteropod". The Athenaeum (829): 851.

- "Geomalacus maculosus General Information". EUNIS biodiversity database. European Environment Agency (EEA). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Simroth, H. (1894). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss der portugiesischen und der ostafrikanischen Nacktschnecken-Fauna". Abhandlungen der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft (in German). 18 (3): 289–307, table 1, figure 1, table 2, figure 1–3. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- Castro, J. da Silva (1873). "Mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles du Portugal. Espèces nouvelles ou peu connues". Jornal de Sciencias Mathematicas, Physicas, e Naturaes (in French). 4: 241–246. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- Simpson, D. P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- Taylor, J. W. (1907). Monograph of the land and freshwater Mollusca of the British Isles. Testacellidae. Limacidae. Arionidae. pt 8–14. Leeds: Taylor brothers. pp. 253–259. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "Geomalacus Allman, 1843". MolluscaBase. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Wade, C. M., Mordan, P. B. & Clarke, B. (2001). "A phylogeny of the land snails (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1465): 413–422. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1372. PMC 1088622. PMID 11270439.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

-

. Conservation Status Assessment Report. National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland. February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help);|contribution=ignored (help) 9 pp. - Kerney, M. P; Cameron, A. D.; Jungbluth, J. H. (1983). Die Landschnecken Nord- und Mitteleuropas (in German). Hamburg and Berlin: Verlag Paul Parey. p. 138. ISBN 978-3-490-17918-0.

- O'Hanlon, A.; Feeney, K.; Dockery, P.; Gormally, M. J. (10 July 2017). "Quantifying phenotype-environment matching in the protected Kerry spotted slug (Mollusca: Gastropoda) using digital photography: exposure to UV radiation determines cryptic colour morphs". Frontiers in Zoology. 14: 35. doi:10.1186/s12983-017-0218-9. PMC 5504635. PMID 28702067.

- Scharff, R. F. (1891). The slugs of Ireland Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. The Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society, volume IV., series II. Dublin, Royal Dublin Society; London, Williams & Norgate. 513–563. Cited pages: 551 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine–556.

- Godwin-Austen, H. H. (1882). Land and freshwater mollusca of India, including South Arabia, Baluchistan, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Nepal, Burma, Pegu, Tenasserim, Malaya Peninsula, Ceylon and other islands of the Indian Ocean; Supplementary to Masers Theobald and Hanley's Conchologica Indica. Plates to Volume I. Taylor and Francis, London. Plate XII Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, figure 5.

- (in German) Simroth, H. (1891). "Die nacktschnecken der portugiesisch-azorischen fauna in ihrem Verhältnis zu denen der paläarktischen region überhaupt" Archived 2016-09-02 at the Wayback Machine. Nova Acta Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae Germanicae Naturae Curiosorum 56(1): 201–424, Tab. IX-XVIII. Halle. Geomalacus maculosus is on page 351 Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine–355.

- (in French) Germain L. (1930). Mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles. Première partie. Faune Fr., lechevalier, Paris, 21: 477 pp.

- Quick H. E. (1960). "British slugs (Pulmonata; Testacellidae, Arionidae, Limacidae". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Zoology 6(3): 103 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine-226.

- Platts, E. A.; Speight, M. C. D. (1988). "The taxonomy and distribution of the Kerry slug Geomalacus maculosus Allman, 1843 (Mollusca: Arionidae) with a discussion of its status as a threatened species". Irish Naturalists' Journal. 22 (10): 417–430.

- Pilsbry H. A. (1898). "Phylogeny of the genera of Arionidae". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London 3: 94 Archived 2016-06-02 at the Wayback Machine-104.

- Godwin-Austen, H.H. (1882). Land and freshwater mollusca of India, including South Arabia, Baluchistan, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Nepal, Burma, Pegu, Tenasserim, Malaya Peninsula, Ceylon and other islands of the Indian Ocean; Supplementary to Masers Theobald and Hanley's Conchologica Indica. Volume 1. v 1. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 60–65. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Family summary for Arionidae" Archived 2008-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. AnimalBase, last change 12-06-2009, accessed 4 August 2010.

- Kearney, Jon (2010). "Kerry slug (Geomalacus maculosus Allman 1843) recorded at Lettercraffroe, Co. Galway". Irish Naturalists' Journal. 31: 68–69.

- "Plano Sectorial da Rede Natura 2000. "Fauna, Invertebrados"" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Portugal: Instituto de Conservação da Natureza e da Biodiversidade. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Species Action Plan. Kerry Slug. Geomalacus maculosus (PDF). Ireland: National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland. January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2007. 9 pp.

- Viney, Michael (5 May 2010). "Problems with plan for protection of slugs". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- Mascheretti, S.; Rogatcheva, M.B.; Gündüz, İ.; Fredga, K.; Searle, J.B. (2003). "How did pygmy shrews colonize Ireland? Clues from a phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1524): 1593–1599. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2406. PMC 1691416. PMID 12908980.

- Reich, I.; Gormally, M.; Allcock, A.L.; Mc Donnell, R.; Castillejo, J.; Iglesias, J.; Quinteiro, J; Smith, C.J. (2015). "Genetic study reveals close link between Irish and Northern Spanish specimens of the protected Lusitanian slug Geomalacus maculosus". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 116: 156–168. doi:10.1111/bij.12568.

- Geomalacus maculosus. EUNIS (European Nature Information System), European Topic Centre on Biological Diversity, European Environment Agency. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Ketch, Catherine (2012), Kerry Slug researcher visits Baile Bhúirne and Beara, The Corkman

- Threat Response Plan Archived 2016-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, Ireland: National Parks & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 24 June 2012

- Castillejo, J. (1998). Guia de las babosas Ibericas (in Spanish). Santiago de Compostela: Real Academia de Ciencias.

- Castillejo, J.; Iglesias, J. (2007). Geomalacus (Geomalacus) maculosus Allman, 1843. Libro Rojo de los Invertebrados de España (PDF) (in Spanish). pp. 351–352. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- Sierra de los Ancares Archived 2011-09-06 at the Wayback Machine, Urugallo cantábrico website (LIFE Programme: Capercaillie Project)

- "Ancares (ES0000374)". EEA. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Ancares-Courel (ES1120001)". EEA. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Ramos, M. A. (1998). "Implementing the habitats directive for mollusc species in Spain". Journal of Conchology. Molluscan Conservation: A Strategy for the 21st Century, Special Publication (2): 125–132.

- Patrão, C.; Assis, J.; Rufino, M.; Silva, G.; Backeljau, T.; Castilho, R. (2015). "Habitat suitability modelling of four terrestrial slug species in the Iberian Peninsula (Arionidae: Geomalacus species)". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 81 (4): 427–434. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyv018.

- Mc Donnell, R.; O'Meara, K.; Nelson, B.; Marnell, F.; Gormally, M. (2013). "Revised distribution and habitat associations for the protected slug Geomalacus maculosus (Gastropoda, Arionidae) in Ireland". Basteria. 77 (1–3): 33–37.

- Castillejo, J.; Garrido, C.; Iglesias, J (1994). "The slugs of the genus Geomalacus Allman, 1843, from the Iberian peninsula (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Arionidae)". Basteria. 58: 15–26.

- Wiesniewski, P. J. (2000). "Husbandry and breeding of Kerry spotted slug". International Zoo Yearbook. 37 (1): 319–321. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2000.tb00736.x. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. (subscription required)

- Rodriguez, T.; Ondina, P.; Outeiro, A.; Castillejo, J. (1993). "Slugs of Portugal. III. Revision of the genus Geomalacus Allman, 1843 (Gastropoda:Pulmonata: Arionidae)" (PDF). Veliger. 36 (2): 145–159. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Rogers, T. (1900). "The eggs of the Kerry Slug Geomalacus maculosus, Allman". Irish Naturalist. 9: 168–170, plate 5. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

- Giordani I.; Hynes T.; Reich I.; Mc Donnell R. J.; Gormally M. J. (2014). "Tetanocera elata (Diptera: Sciomyzidae) Larvae Feed on Protected Slug Species Geomalacus maculosus (Gastropoda: Arionidae): First Record of Predation". Journal of Insect Behavior. 27 (5): 652–656. doi:10.1007/s10905-014-9457-1.

-

. Conservation Status Assessment Report. National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland. 25 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help);|contribution=ignored (help) - "Checklist of protected & rare species in Ireland" (PDF). National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland. 7 January 2009. 15 pp., cited page: p. 12. mentioned here on pg 20 and 22

- Eionet (European Environment Information and Observation Network), European Topic Centre on Biological Diversity. "Geomalacus maculosus". Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- SI 94/1997 as amended by EC (Natural Habitats) (Amendment) Regulations SI 233/1998 and SI 378/2005.

- Book (Eisb), Electronic Irish Statute. "Wildlife Act, 1976 (Protection of Wild Animals) Regulations, 1990". Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- "By the Time We've Saved the Slugs, the Snails and Those Viking Graves, Who Will Save the Commuter?". Daily Mail (London). McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2014 from Questia Online Library (subscription required)

- Bruce, Helen (January 2008). "On the wild frontier; (1) Under threat: The otter is a perennial favourite for children and nature enthusiasts, with its expressive features, dog-like playfulness, grace in the water and furry coat (2) Image problem: Not as cuddly as the otter but the Kerry Slug is still in need of our help". Daily Mail (London). Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Department Of Agriculture, Food & the Marine (2009). "Kerry Slug and Otter Guidelines". The Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Commission v Ireland C-183/05. (The court case did not just involve the Kerry slug, but considered wider transposition failures by Ireland).

- Kerry Slug Survey of Ireland (Official Website) Archived 2009-07-25 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Mc Donnell, R.J. and Gormley M.J. (2011). Distribution and population dynamics of the Kerry Slug, Irish Wildlife Manual No 54, National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Dublin

Further reading

- Allman, G. J. (1844). "On a new genus of terrestrial gastropod". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1843: 77.

- Allman, G. J. (1846). "Description of a new genus of pulmonary gastropods". Annals and Magazine of Natural History 17: 297–299, plate 9.

- Boycott A. E., Oldham C. (1930). "The food of Geomalacus maculosus". Journal of Conchology. 19: 36.

- Oldham, C. (1942). "Notes on Geomaculus maculosus". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London 25.

- Heynemann, D. F. (1873). "On the French species of the genus Geomalacus". Annals and Magazine of Natural History, pages 271–275.

- (in German) Heynemann, D. F. (1869). "Zur Kenntniss von Geomalacus". Nachrichtsblatt der Deutschen Malakozoologischen Gesellschaft, pages 165–168.

- (in German) Heynemann, D. F. (1871). "Geomalacus maculosus". Nachrichtsblatt der Deutschen Malakozoologischen Gesellschaft 3(1): 126.

- (in German) Heynemann, D. F. (1873). "Ueber Geomalacus". Malakozoologische Blätter xxi: 25–36, table 1, fig. 1-6.

- Moorkens, E. A. (2006). "Irish non-marine molluscs – an evaluation of species threat status". Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society 30: 348–371. OCLC 265510707.

- Reich, Inga; Mc Donnell, Rory; Mc Inerney, Cathal; Callanan, Shane; Gormally, Michael (February 2017). "EU-protected slug Geomalacus maculosus and sympatric Lehmannia marginata in conifer plantations: what does mark-recapture method reveal about population densities?". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 83 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyw039. ISSN 0260-1230.

- Scharff, R. F. (1892). "Land and freshwater shells peculiar to the British Isles". Nature. 46: 173. doi:10.1038/046173d0.

- Scharff, R. F. (1893). "Note on the geographical distribution of Geomalacus maculosus Allman, in Ireland". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London. 1: 17–18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geomalacus maculosus. |

- Geomalacus maculosus at Animalbase taxonomy, short description, distribution, biology, status (threats), images

- Bridges & Species: Post-Glacial Colonisation

- A photograph of a live individual

- Mollusc Ireland