Kepler-56b

Kepler-56b (KOI-1241.02)[2] is an exoplanet located roughly 3,060 light years away. It is somewhat larger than Neptune[3] and orbits its parent star Kepler-56 and was discovered in 2013 by the Kepler Space Telescope.

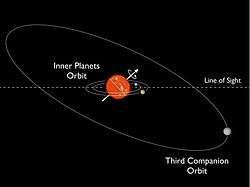

A diagram of the planetary system of Kepler-56 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Daniel Huber et al.[1] |

| Discovery date | 16 October 2013 |

| Transit method | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 0.1028 ± 0.0037 AU (15,380,000 ± 550,000 km)[1] | |

| 10.5016+0.0011 −0.0010[1] d | |

| Star | Kepler-56 |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 6.51+0.29 −0.28[1] R⊕ |

| Mass | 22.1+3.9 −3.6[1] M⊕ |

Mean density | 0.442+0.080 −0.072 g cm−3 |

Planetary orbit

Kepler-56b is about 0.1028 AU away from its host star[1] (about one-tenth of the distance between Earth to the Sun), making it even closer to its parent star than Mercury and Venus. It takes 10.5 days for Kepler-56b to complete a full orbit around Kepler-56.[1] Further research shows that Kepler-56b's orbit is about 45° misaligned to the host star's equator. Later radial velocity measurements have revealed evidence of a gravitational perturbation but currently it is not clear if it is a nearby star or a third planet (a possible Kepler-56d).

Both Kepler-56b and Kepler-56c will be devoured by their parent star in about 130 and 155 million years.[4] Even further research shows that it will have its atmosphere boiled away by intense heat from the star, and it will be stretched by the strengthening stellar tides.[4] The measured mass of Kepler-56b is about 30% larger than Neptune's mass, but its radius is roughly 70% larger than Neptune's. Therefore, Kepler-56b should have a hydrogen/helium envelope containing a significant fraction of its total mass.[5][6] Like Kepler-11b and Kepler-11c, the envelope's light elements are susceptible to photo-evaporation caused by radiation from the central star. For example, it has been calculated that Kepler-11c lost over 50% of its hydrogen/helium envelope after formation.[7] However, the larger mass of Kepler-56b, compared to that of Kepler-11c, reduces the efficiency of mass loss.[7] Nonetheless, the planet may have been significantly more massive in the past and may keep losing mass in the future.

References

- Huber, D.; et al. (2013). "Stellar Spin-Orbit Misalignment in a Multiplanet System". Science. 342 (6156): 331. arXiv:1310.4503. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..331H. doi:10.1126/science.1242066. PMID 24136961.

- "KOI-1241.02". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- "NASA Exoplanet Archive". NASA Exoplanet Archive. Operated by the California Institute of Technology, under contract with NASA.

- Charles Poladian (2014-06-03). "Cosmic Snack: Planets Kepler-56b And Kepler-56c Will Be Swallowed Whole By Host Star". International Business Times. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Lissauer, J. J.; Hubickyj, O.; D'Angelo, G.; Bodenheimer, P. (2009). "Models of Jupiter's growth incorporating thermal and hydrodynamic constraints". Icarus. 199 (2): 338–350. arXiv:0810.5186. Bibcode:2009Icar..199..338L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.10.004.

- D'Angelo, G.; Weidenschilling, S. J.; Lissauer, J. J.; Bodenheimer, P. (2014). "Growth of Jupiter: Enhancement of core accretion by a voluminous low-mass envelope". Icarus. 241: 298–312. arXiv:1405.7305. Bibcode:2014Icar..241..298D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.06.029.

- D'Angelo, G.; Bodenheimer, P. (2016). "In Situ and Ex Situ Formation Models of Kepler 11 Planets". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (1): id. 33. arXiv:1606.08088. Bibcode:2016ApJ...828...33D. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/828/1/33.

Further reading

- Steffen, Jason H; Fabrycky, Daniel C; Agol, Eric; et al. (20 August 2012). "Transit Timing Observations from Kepler: VII. Confirmation of 27 planets in 13 multiplanet systems via Transit Timing Variations and orbital stability". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 428 (2): 1077. arXiv:1208.3499. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.428.1077S. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts090.

External links

- "Kepler-56b". kepler.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- Megan Smith (8 June 2014). "Star to Swallow not One, but Two Exoplanets". Futurism LLC.