Kenmore Asylum

Kenmore Asylum, also known as Kenmore Hospital or Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital is a heritage-listed decommissioned psychiatric hospital located in Goulburn, a town in New South Wales, Australia. Construction began in 1894 and opened in 1895, capable of housing 700 patients. In March 1941, the Australian Army accepted an offer from the New South Government, where the Kenmore Asylum would be the site for a military hospital. As a result, patients located at the asylum were moved to various mental institutions in Sydney. In 1946, the Australian Department of Health resumed control of Kenmore Asylum after the army moved out. The property was sold in 2003 and resold in 2010. It is described as one of Australia's "most haunted locations".[1][2][3]

| Kenmore Asylum | |

|---|---|

Main building of Kenmore Asylum in 2006 | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Goulburn, New South Wales, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 34°43′08″S 149°45′20″E |

| Organisation | |

| Type | Disused mental hospital |

| Services | |

| Beds | 700 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1895 |

| Closed | 2003[lower-alpha 1] |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in Australia |

| Other links | List of Australian psychiatric institutions |

Building details | |

| |

| Alternative names |

|

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Free Edwardian/Federation |

| Owner | Australia China International Pty Ltd |

| Grounds | 137.8 hectares (341 acres) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Walter Liberty Vernon |

| Architecture firm | Colonial Architect of New South Wales |

| Other designers | Dr Frederick Norton Manning |

| Main contractor | John Baldwin & J. C. O'Brien |

The property was sold to Australia China International Pty Ltd in March 2015 and it is planned to restore the once derelict building as Kenmore Gardens with likely uses to include retirement living, government services, or educational facilities.[4] It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 1 April 2005.[5]

History

Background and construction

In October 1879, 340.5 acres (137.8 ha) of land of the Kenmore Estate was purchased by the government at a cost of £1,252. Frederick Norton Manning, who was recently appointed as the colony's Inspector-General of the Insane purchased the estate, making it his first major achievement in his new role.[2] A new hospital for the site was planned, in which the first constructed wards were intended for chronic cases which have accumulated in existing hospitals from the southern districts of the New South Wales colony.[6] Several concerns were raised about the location of the proposed hospital. Although Manning considered the site to be "very suitable", questions were raised about the water supply, and there was little outlook. Members of the Public Works Committee agreed that the Rossiville Estate was a more suitable site for a new hospital, providing that a sewerage scheme could not be obtained without polluting the Goulburn water supply.[7]

The estimated cost of building the asylum was £150,000; the cost was spread over a period of five years, and up to 650 patients could accommodate it.[8] The first construction contracts were permitted in 1894, the major one going to John Baldwin, a builder from Sydney for £12,760. Local Goulburn builder J.C. O'Brien was granted the second contract for £923, where his contract involved the erection of a number of buildings in brick, as well as a few temporal wooden structures. In O'Brien's contract, it also called for the erection of a small brick "special ward" for patients who became violent or uncontrollable, although the first patients for the asylum would be chosen for their quiet and industrious nature. Violent and uncontrollable patients would be kept under lock and key.[2]

By the end of 1894, the asylum was ready to temporarily accommodate 140 patients, with several wards of the hospital yet to be complete.[9] In January 1895, the first personnel for the asylum were officially appointed, and upon opening, 152 patients from other hospitals were transferred to Kenmore; of the 152 patients, 146 of them were male.[10][11] Despite several wards being opened for operation, the asylum was anticipated for completion by June 1897 to provide services for the southern regions of New South Wales.[12] By 1896, a considerable amount of work was made, where edifices of brick now lay upon several acres of land. The new contractors, Messrs, Parry and Farley, hoped to get through their contract by the end of the year despite it only intending to complete one third of the work. The number of patients rose up to 156 in that year. In addition, there were temporary offices and quarters for the staff, which composed of two officers, 17 attendants, a cook, a laundress and a needlewoman.[13]

Further progress was made in 1897, with most of the prominent buildings being completed and taken in possession by the staff and patients. It began assuming the appearance of a township, and £70,000 was already spent on its construction between a three to four year period. A further £70,000 was estimated to complete the complex. A new contract was also made, and it composed of a nurses' and attendants' home, which stand on either side of the administrative block and thus would complete the front elevation of the asylum. The remainder of the work primarily consisted of the construction of additional wards which stretched outwards towards a nearby river, forming a "V-shape" from the central quadrangle. In 1897, 150 male and 42 female patients resided at the asylum.[14] By 1901, Kenmore Asylum had been completed, although small additions were expected in the future.[15]

20th century

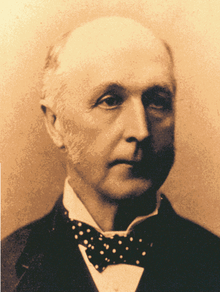

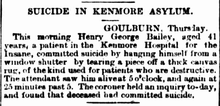

Several deaths at Kenmore began to plague the complex. In 1902, Henry George Bailey, a patient who was admitted to the asylum, committed suicide by hanging himself from a window shutter, using a thick canvas rug by tearing a thick piece off of it. These rugs were specifically made to be strong because they were used on violent patients. Due to his violent and homicidal tenancies, Bailey was visited by an attendant every half-hour. At 5 o'clock, the attendant saw Bailey sleeping, but upon returning to him 25 minutes after the last visit, Bailey had committed suicide. An inquiry was held by the coroner who concluded that he did commit suicide.[16][17] A year later, a second patient who was admitted to the asylum died. The coroner found that the patient died from suffocation, as a result of an epileptic fit.[18] In 1908, a patient was attacked and killed by another resident of the asylum, who struck him on the head with a holystone. The patient, Prince Dean, had a history of hitting other patients and explained why he had struck him, saying it was "for fun". At the time of the incident, the victim, John Cubitt, was scrubbing floors with Dean.[19][20]

In 1909, tenders were received for the erection of two convalescent wards, one each for males and females. A new admission block and doctor's quarters was also proposed. The accepted tender involved a new admission block and a new administration block, costing £10,995.[21][22] The asylum suffered considerable damage in 1912, where a fire broke out at 2 o'clock in a drying room. All of the clothing in the dryers was destroyed, and furnishings of the room were burnt; in addition, the value of this loss was considerable. The cause was unknown.[23]

Years after the deaths of patients at Kenmore, many more were reported. In 1917, a patient named James Claxton hung himself from a tree, despite being noted as a quiet sociable, well behaved person who never indicated any desire to commit suicide.[24] Two years later, in August 1919, a pneumonic influenza pandemic swept across the asylum and killed 21 more patients; of these, 19 patients were male and two were female.[3] In 1920, Alston Paul Broome was sentenced to death for murdering his wife at the asylum.[25]

Heritage listing

.jpg)

The Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital site is of State significance: as the first purpose-built, whole complex for mental health care in rural NSW; as the largest example of the work of W.L. Vernon (the first Government Architect); and for having been used and maintained by the one agency for the original purpose continuously (except for the brief Defence period during WWII).[5]

The Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital complex is a representation, in physical form, of the changing ideas and policies concerning the treatment of the mentally ill and handicapped people, in the State, spanning one hundred years.[5]

Within the Hospital precinct, and within the actual layout and design of the precinct buildings and landscape, these changing ideals are "laid out" one upon another like successive occupation layers of an archaeological site. The Hospital fabric also clearly evidences the Military occupancy of the site.[5]

The original 1890s Vernon complex of buildings still evidence the features that made Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital one of the most modern psychiatric institution of its day. Many of the buildings which followed the Vernon structures have significant historical associations in their own right and in their functional relationships with the original Vernon buildings.[5]

The early buildings of Kenmore, particularly the "core" Vernon buildings, represent perhaps the finest "corporate" architectural expression of the Edwardian (later Federation) Free style in Australia.[5]

The institution of Kenmore has important links with the community of the locality and region. These links were particularly strong in the early 20th century, when Kenmore was a focal point for regional sporting and cultural activities.[5]

The institution of Kenmore has played a pivotal role in the evolution and development of treatment for the mentally ill and handicapped in the State of NSW.[5]

The farm complex of Kenmore is culturally significant as a physically intact precinct created as an integral part of rehabilitation treatment for the patients of Kenmore. The sporting related functions, particularly the cricket pavilion, are significant as exemplars of the close connection of Kenmore to its community, and the use of sport as an integral part of rehabilitation treatment.[5]

The cemetery complex, and its landscape, is a significant element of the life / death cycle of the Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital. It is one of the few "pauper" cemeteries in the state.[5]

The institutionalisation of psychiatric patients is a function now less practised. A large psychiatric institution, such as Kenmore, although not unique, demonstrates a way of life and a treatment ethic now no longer practised. The layout and design of the core buildings clearly evidence the institutional beliefs and treatments of psychiatric patients in the late 19th century.[5]

The Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital, although not unique as a remnant late 19th century psychiatric hospital, is by its intactness and architectural excellence an exemplar of the structure and philosophy and physical basis of the institution. The hospital also has specific association with those Inspectors General who ran it.[5][26]

Kenmore Asylum was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 1 April 2005 having satisfied the following criteria.[5]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital complex is a representation, in physical form, of the changing ideas and policies concerning the treatment of the mentally ill and handicapped people, in the State, spanning one hundred years.[5]

Within the Hospital precinct, and within the actual layout and design of the precinct buildings and landscape, these changing ideals are "laid out" one upon another like successive occupation layers of an archaeological site. The Hospital fabric also clearly evidences the Military occupancy of the site.[5]

The original 1890s Vernon complex of buildings still evidence the features that made Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital the best planned, the best situated and the most modern psychiatric institution of its day. Many of the buildings which followed the Vernon structures have significant historical associations in their own right and in their functional relationships with the original Vernon buildings.[5][26]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The institution of Kenmore has played a pivotal role in the evolution and development of treatment for the mentally ill and handicapped in the State of NSW.[5]

The hospital has specific associations with those who created the philosophical and physical basis of the institution. The Hospital and its landscape also has specific association with those Inspector Generals who ran it.[5][26]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The early buildings of Kenmore, particularly the "core" Vernon buildings, represent perhaps the finest "corporate" architectural expression of the Edwardian (later Federation) Free style in Australia.[5]

The unity of the building complex, and the quality of the design, detailing and construction is exceptional. The relationship between buildings and landscape is an important reflection of institutional landscape management over a period of one hundred years. The riverside setting on land which slopes gently towards the depression of the river provides Kenmore with an exceptional aspect that is viewed from the major transport (road and rail) to the east. This aspect has been enhanced by the Goulbourn town bypass road and ensures that the town is identified to a large extent by the Kenmore Hospital aspect.[5][26]

The place has strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The institution of Kenmore once had important links with the community of the locality and region. These links were particularly strong in the early 20th century, when Kenmore was a focal point for regional sporting and cultural activities.[5]

With the prohibition of "external" use of the Kenmore playing fields and the virtual "close down" of the majority of the Kenmore buildings, these links with the community (both actual and virtual) are now not much more than historical associations.[5]

However, when the Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital was in its "prime", it was a centre for sporting excellence in the region and great pride was felt by patients, staff and the Goulbourn community in the Kenmore playing fields.[5]

The Hospital is regarded today by the community, former staff and patients in both a positive and negative light. There is the positive contribution of Kenmore to the community; and the negative ethos of psychiatric institutions.[5][26]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The institutionalisation of psychiatric patients is a function now less practiced. A large psychiatric institution, such as Kenmore, although not unique, demonstrates a way of life and a treatment ethic now no longer practised. The layout and design of the core buildings clearly evidence the institutional beliefs and treatments of psychiatric patients in the late 19th century.[5]

The 1990s has seen the de-institutionalisation of eth State's psychiatric care; and the gradual removal from Kenmore is a State and National phenomenon.[5]

The archive files of the Kenmore Hospital mental health activities elicit numerous requests for the provision of historical and archival data. The Archive si almost complete (extending back to Patient No. 1), and is of great historical importance. The Archives should be curated and conserved in proper condition.[5]

The services reticulation within the site is significant in its own right. The "oral history" archive retained by the past and present artisans is of cultural significance. This oral history is being lost because trades expertise is being lost to the campus, and with it the oral history record associated with the twentieth century history of the place.[5]

Kenmore has traditionally played a "service" role. With the closure of that service period, the opportunity to assess and interpret the role of the institution is now being taken. A Kenmore museum is currently being relocated to one of the historical ward buildings. The core precinct within the campus is virtually a living museum. There is an opportunity to reinterpret the whole role of psychiatric treatment in the State of Kenmore.[5][26]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Whereas psychiatric hospitals were once viable and important institutions dealing with the mentally ill and handicapped, the radical changes in recent years in the treatment of mental illness has resulted in very low rates of institutionalisation and the closure of purpose-built facilities. Although part of Kenmore have been handed over for alternative uses, it is the most intact of the large psychiatric institutions (apart from the modern hospitals at Stockton and Orange), Kirkbride (Callan Park, which was the first purpose-built hospital of the type, has now been handed over to alternative uses. Kenmore is therefore the last, substantially 19th century hospital, to remain as a functioning hospital for the mentally ill.[5][26]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

The Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital, although not unique as a remnant late 19th century psychiatric hospital, is by its intactness and architectural excellence an exemplar of the structure and philosophy of psychiatric institutions of its time.[5][26]

Notes

- The Kenmore Hospital remains opened on the original site, but not in the original wards.[1]

References

- Walsh, G. (18 February 2013). "Last Kenmore artefact in time for 150th b'day". Goulburn Post. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Kenmore Hospital Complex". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Abandoned Kenmore insane asylum 'undoubtedly haunted'". Nine News. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "New Kenmore owners want to restore it to former glory". Goulburn Post. 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Kenmore Hospital Precinct". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01728. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 20 July 1882. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "The Proposed Lunatic Asylum at Rossiville". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, NSW: National Library of Australia. 5 June 1890. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Parliament". The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 6 October 1894. p. 694. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "Inspector General of the Insane, Report for 1894, in Votes and Proceedings 1894-95". Votes and Proceedings. 5: 490. 1894–95.

- NSW Government Blue Book. Sydney, NSW: Government of New South Wales. 1897. p. 5.

- "Inspector General of the Insane, Report for 1895, in Votes and Proceedings 1896". Votes and Proceedings. 3: 385–391. 1896.

- "Inspector General of the Insane, Report for 1896, in Votes and Proceedings 1897". Votes and Proceedings. 7: 896. 1897.

- "The Kenmore Hospital for the Insane". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, NSW: National Library of Australia. 24 October 1896. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "The Kenmore Hospital for the Insane". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, NSW: National Library of Australia. 15 April 1897. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "The Kenmore Hospital for the Insane". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, NSW: National Library of Australia. 30 May 1901. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Suicide in Kenmore Asylum". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 17 January 1902. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Suicide at an Asylum". The Australian Star. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 17 January 1902. p. 7. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Death at Kenmore Asylum". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney, NSW: National Library of Australia. 17 February 1903. p. 6. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Death of a Kenmore Patient". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, NSW: National Library of Australia. 15 August 1908. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Tragedy in an Asylum". The Argus. Melbourne, Victoria: National Library of Australia. 15 August 1908. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Extensions at Kenmore". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, New South Wales: National Library of Australia. 15 April 1909. p. 4. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Kenmore Buildings". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. New South Wales, Australia. 30 November 1909. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Fire at Kenmore". Leader. Orange, New South Wales: National Library of Australia. 31 July 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Tragedy at Kenmore". Young Witness. National Library of Australia. 10 July 1917. p. 1. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "The Kenmore Murder". Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Goulburn, New South Wales: National Library of Australia. 29 April 1920. p. 2. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Freeman 1999:25

Bibliography

- Graham Brooks & Associates (2006). Heritage Impact Assessment: Proposed Subdivision, Former Kenmore Hospital, Goulburn.

- Leighton-Daly, Phil (2014). Kenmore Psychiatric Hospital 'Wednesday's Child' - Volume 1.

- Parsons Brinckerhoff P/L (2003). Draft Kenmore Master Plan - Goulburn Local Environment Plan 1990.

- Peter Freeman P/L in association with Donald Ellsmore P/L (1999). Conservation Management Plan Review: Kenmore Hospital, Goulburn.

- Lester Firth P/L (1983). Goulburn Heritage Study: final report.

Attribution

![]()

External links

![]()