Kayts

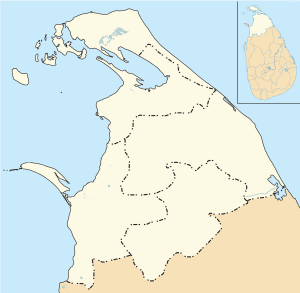

Kayts (Tamil: ஊர்காவற்துறை, romanized: Ūrkāvaṟtuṟai, Sinhala: කයිට්ස්, romanized: kayiṭs), is one of the important villages in Velanai Island which is a small island off the coast of the Jaffna Peninsula in northern Sri Lanka.[1] There are number of other villages within the Velanai Islands such as Allaippiddi, Mankumpan, Velanai, Saravanai, Puliyankoodal, Suruvil, Naranthanai, Karampon and Melinchimunai.

Kayts ஊர்காவற்துறை කයිට්ස් | |

|---|---|

Kayts  Kayts | |

| Coordinates: 9°40′0″N 79°52′0″E | |

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Province | Northern |

| District | Jaffna |

| DS Division | Islands North |

Most of the people are Tamils. There are number of Hindu temples as well as church and a mosque. The island is also served by a dozen schools.

Since 1983 Kayts Island has also been the scene of violence as part of the Sri Lankan Civil War, including the Allaipiddy massacre.[2][3] On 8 August 1992, Major General Denzil Kobbekaduwa and Commodore Mohan Jayamaha were killed along with several senior army and navy officers when their Land Rover hit a land mine off Araly Point in Kayts.[4]

Etymology

The name Kayts is of colonial origin. The name is derived from the Portuguese "Caes dos Elefantes" meaning "Elephant's Quay", often just shortened to Cais. It was named such because elephants were shipped from here to India.[5] The present term evolved further as Kayts under Dutch rule.[6]

The native Tamil name Ūrkavathurai means "Port which guards the Country".[7] This name is again derived from the original Tamil term Ūrathurai, derived from the Tamil words Uru meaning "ship" or "shooner", and thurai meaning "port".[8] The earliest reference to this is found in two Tamil inscriptions of the 12th century AD, one found in Thiruvalangadu, Tamil Nadu issued by Rajadhiraja Chola II and one found in Nainativu issued by Parakramabahu I.[9][10]

Other scholars derive the name from the Pali name Ūrātota meaning "Pig port", referring to a legend surrounding the Śakra buddhist deity, who swam from India to this place in the form of a pig.[11] Earliest reference to this is found in the Pali chronicle Pujavaliya of the 13th century AD.

History

The earliest inscription mentioning Kayts or Ūrathurai is that of a Tamil Chola inscription of the 12th century AD discovered in Fort Hammenhiel, referring to the 9th century AD Chola general of the King Parantaka Chola II, who died in a battle field in Kayts.[12] The 13th century AD Pali chronicle Pujavaliya, mentions that Mahinda IV vanquished a Tamil king who landed at Hurātota from the Cola country.[13] A Tamil 12th century AD inscription issued by Rajadhiraja Chola II found in Thiruvalangadu, Tamil Nadu also mentions the Chola King taking elephants from Kayts and other places such as Valikamam and Mattivazh.[9]

Archeological remains found in Kayts indicates that Kayts was a harbour for foreign vessels.[14] The Tamil 12th century AD inscription of Nainativu issued by Parakramabahu I mentions Kayts as a port where foreigner must first land for trading.[10]

Kayts was part of the Jaffna Kingdom. Under the chieftainship of Migapulle Arachchi, did a group of Christians revolt against the Jaffna King Cankili II, who thereupon sought refugee in Kayts and asked the Portuguese for assistance.[15]

References

- "District Secretariat Jaffna_Divisional Secretariat Location and Map". ds.gov.lk. Gov of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 2014-07-29.

- K. T. Rajasingham (29 September 2001). "Sri Lanka: The Untold Story : Chapter 8: Pan Sinhalese board of ministers - A Sinhalese ploy". Asia Times Online. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Special Report No.2". University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), Sri Lanka in association with Pax Christi (an international Catholic peacemaking movement). Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Gen. Denzil Kobbekaduwa, who led from the front Archived 2014-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

- The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. The Branch. 1909.

- Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. p. 54.

- Wright, Arnold (1907). Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120613355.

- TamilNet. "TamilNet". www.tamilnet.com. Retrieved 2018-01-10.

- Pandaraththar, Sadasiva. History of Cholas Vol II.

- University of Ceylon Review. 1963.

- Bassett, Ralph Henry (1934). Romantic Ceylon: Its History, Legend, and Story. Asian Educational Services. p. 285. ISBN 9788120612747.

- Ancient Ceylon. Department of Archaeology, Sri Lanka. 1979. p. 158.

- Epigraphia Zeylanica, Being Lithic and Other Inscriptions of Ceylon. government of Ceylon. 1955. p. 108.

- Guṇavardhana, Raṇavīra; Rōhaṇadīra, Măndis (2000). History and Archaeology of Sri Lanka. Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural and Religious Affairs. p. 450. ISBN 9789556131086.

- Silva, K. M. De (1981). A History of Sri Lanka. University of California Press. pp. 116. ISBN 9780520043206.

cankili kayts.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kayts. |