Kaumualii

Kaumualiʻi (c. 1778–May 26, 1824) was the last independent aliʻi nui (supreme ruler of the island) of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau before becoming a vassal of Kamehameha I within the unified Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1810. He was the 23rd high chief of Kauaʻi and reigned from 1794–1810.

| Kaumualiʻi | |

|---|---|

| Aliʻi ʻAimoku of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau | |

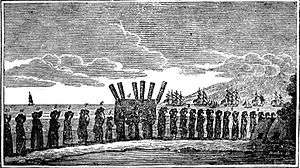

Kaumualiʻi and Kaʻahumanu, number 8, in the funeral procession of Queen Keōpūolani, 1823. | |

| Born | c. 1778 Holoholokū Heiau, Wailua |

| Died | May 26, 1824 (aged 46) Honolulu |

| Burial | May 30, 1824 |

| Spouse | Kawalu Kaʻapuwai Kapuaʻamohu Naluahi Kekaihaʻakūlou Kaʻahumanu |

| Issue | Humehume Kealiʻiahonui Kinoiki Kekaulike |

| Father | Kāʻeokūlani, Regent of Maui and Molokaʻi |

| Mother | Kamakahelei, Aliʻi Aimoku of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau |

Although he was sometimes known as George Kaumualiʻi, he should not be confused with his son, who is more commonly known by that name.

In Hanama'ulu, the King Kaumuali'i Elementary School is named after Kauai's last reigning chief.

Family

Kaumualiʻi was the only son of Queen Kamakahelei, aliʻi nui of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau, and her husband, Aliʻi Kāʻeokūlani (c. 1754–1794), regent of Maui and Molokaʻi.[1] Kāʻeokūlani was the younger son of Kekaulike, the 23rd Aliʻi Aimoku and Moʻi of Maui. He became the co-king and effectively ruler of Kauaʻi by his marriage.

When Kamakahelei died in 1794, she passed their titles and positions to the 16-year-old Kaumualiʻi, who reigned under the regency of Chief Inamoʻo until he came of age. His first wife and queen was his half-sister Kawalu of O'ahu. His second wife was his niece, Kaʻapuwai Kapuaʻamohu of Kōloa; his third and final wife was the queen regent Kaʻahumanu (1768–1832), Kamehameha's widow.

Unification

Kauaʻi and Niʻihau had eluded Kamehameha's control since he first tried to add them to his kingdom in 1796, a year after Kaumualiʻi became king. At that time, the governor of the Island of Hawai'i led a rebellion against Kamehameha forcing him to return home. Kamehameha tried again in 1803, but disease ravaged his armies, and he called a retreat to heal his men and work on his strategy. Over the next years, Kamehameha amassed the largest armada Hawaiʻi had ever seen: foreign-built schooners and massive war canoes armed with cannons to carry his vast army. Kaumualiʻi decided to negotiate a peaceful resolution rather than resort to bloodshed. The move was supported by Kamehameha as well as the people of Kauaʻi and the foreign sandalwood merchants on the island, whose trade was hurt by the constant feuding. In 1810, Kaumualiʻi became Kamehameha's vassal, and all the islands were united for the first time.[1] Kaumualiʻi continued to serve as Kamehameha's governor of Kauaʻi.

In 1815, a ship from the Russian-American Company the Bering was wrecked on Kaua'i. Another ship, the Isabella was dispatched by RAC Governor Alexander Andreyevich Baranov to retrieve the cargo from the Bering. In 1816, an agreement was signed by Kaumualiʻi to grant Dr. Georg Anton Schäffer and his Russian crew to build the forts Alexander and Barclay-de-Tolly. The Hawaiian fort, Pa'ula'ula o Hipo, in later decades was renamed Fort Elizabeth and attributed to the Russians[2]. Construction was begun in 1817 but, by fall of that year, the Russians were expelled.

In 1817, Kaumuali'i married Kekaihaʻakūlou who became known as Deborah Kapule.[1]

Kamehameha I died in 1819, and the Hawaiians grew fearful that Kaumualiʻi would sever Kauaʻi's relationship with the united Hawaiʻi. Kamehameha's widow, Kaʻahumanu, was the effective political force in the kingdom. On September 16, 1821, the new young King Kamehameha II arrived and invited Kaumualiʻi aboard his ship. That night, they sailed away to Honolulu, where Kaumualiʻi was effectively under house arrest.[3]:138–146 To make the domination clear, Kaʻahumanu forced him to marry her to ensure the island chain's stable union. They remained officially married until his death on May 26, 1824, but had no children. By his wishes, his body was taken to Mau'i, and buried next to Queen Keōpūolani[3]:223 at the tomb of Hale Kamani.

Kaumualiʻi was popular among both his people and foreigners who visited and worked on his islands. Captain George Vancouver, who had given the young king a flock of sheep as a gift in 1792, was thanked with a lavish banquet and described his host glowingly. Kaumualiʻi was described as handsome, likeable, and courteous, as well as a capable leader. Upon his death, he was sincerely mourned by the people of Kauaʻi.[3]:224

Successors

After Kaumualiʻi's death in 1824, his son by a commoner, George "Prince" Kaumualiʻi Humehume (1797–1826), also known as George Tamoree, attempted to re-establish the independence of Kauaʻi but was also eventually captured and taken to Honolulu. Humehume died of influenza in Honolulu. He had three offspring, a son who died young, a daughter born in 1821 that was given away to another chiefess on Kaua'i named Kamakahi, and a third female child named Harriet Kawahinekipi Kaumualiʻi. Humehume's half-brother Kealiʻiahonui was also forced to marry Kaʻahumanu. Kaʻahumanu would later abandon Kealiʻiahonui and embrace Christianity. Kealiʻiahonui later married Princess Kekauōnohi, the Governess of Mau'i and Kauaʻi, who was a widow of Kamehameha II.

King Kaumualiʻi's granddaughter, Kapiʻolani (1834–1899) of Hilo (eldest daughter of Kaumualiʻi's daughter Kekaulike Kinoiki) married king Kalākaua. In 1874, the couple was elected by the Hawaiian legislature as King and Queen of the Hawaiian Islands as king Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani. Kapi'olani's youngest sister, Princess Victoria Kuhio Kinoike Kekaulike (1843–1884) of Hilo, was later appointed Governor of the island of Kauaʻi, Princess and Royal Highness. Princess Victoria's other sister, Princess Virginia Kapoʻoloku Poʻomaikelani (1839–1895), succeeded her sister as Governor of the island of Kauaʻi and was made Guardian of the Royal Tombs.

Hawaii Route 50 on Kauaʻi is named "Kaumualiʻi Highway" in the honor of Kaua'i's last king.

See also

References

- Daniel Harrington. "Kauaʻi History". Hawaiian Encyclopedia. Mutual Publishing. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- Mills, Peter (2002). Hawai'i's Russian Adventure. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Hiram Bingham I (1855) [1848]. A Residence of Twenty-one Years in the Sandwich Islands (Third ed.). H.D. Goodwin.

External links

- "King Kaumualii Profile". Historical pamphlet on Kaumualiʻi. From coco-palms.com. Retrieved December 27, 2006.

| Preceded by Queen Kamakahelei |

Aliʻi ʻAimoku of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau 1795–1810 |

Succeeded by Kingdom of Hawaii |

| Preceded by first |

Royal Governor of Kauaʻi 1810–1824 |

Succeeded by Kahalaiʻa Luanuʻu |