Katrina Wolf Murat

Katrina Wolf Murat (Countess Murat; August 20, 1824 – March 13, 1910) was a German-born American pioneer. She was the first European woman in Denver, and the maker of the first United States flag in Colorado.[1]

.png)

Early years

Katrina Wolf was born in Heidelsheim, Baden, August 20, 1824.[1][2] Her father was either a Prussian vintner,[3] or German innkeeper.[4]

There are various descriptions of her marriage(s) and how she reached the United States.

- An account by the Daughters of the American Revolution (1917) states that she married a wealthy German and came to the United States with him in 1848. After his death, she married Count Henry Murat, of a distinguished French family.[1]

- Fetter (2004) gives two versions of events. In one version, Katrina first married Mr. Stolsenberger, crossed the Great Plains with him, and inherited US$75,000 upon his death. She subsequently met Henri, a dentist, in San Francisco in 1854 and after marriage, they spent her inheritance on a European honeymoon. A second version describes Henri claiming that his uncle was Joachim Murat. Forced to leave France by the Bourbon kings, Henri escaped to Germany, and found employment at Katrina's father's estate. After Henri and Katrina married, they sailed for the U.S. in 1848.[3]

- Talbot (1896) states that "Catherine" married Hienrich, Count Murat in 1846.[2]

- Summers (2011) recounts from a 1901 New York Times article that she married Count Henri Murat in 1848, that he was a great nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, and that they came to the U.S. in 1852.[4]

Countess Murat

Shortly after their marriage, Count and Countess Murat honeymooned in Europe, and while there, purchased a red merino petticoat.[1] Joining the Pike's Peak Gold Rush, the Murats settled in Montana City, Colorado (or Aurora, Colorado) in 1848. The mining camps of California, Montana, and Nevada were visited by the party of which she and her husband were members during those days when the gold fever was an epidemic, and when the vaguest rumors sufficed to draw the entire population of one camp to another, however distant. The journeys were usually made in "prairie schooners" drawn by oxen.[2]

During an interval of two years, the Murats visited Europe, the trip being made overland from Colorado to New Orleans, thence to Le Havre via New York City. In 1858, they returned to Colorado,[2] and the following year, with a partner named David Smoke, they became proprietors of the Eldorado Hotel in Auraria, Denver, selling the business after three months. They then moved to the Denver side of Cherry Creek where they made a living operating a bakery, a barbershop, and a laundry.[1] His occupations were barber, dentist, gambler, and innkeeper.[4]

Murat received a commission to make the first American flag for Colorado, which flew from the Eldorado's 50-foot flagpole on May 1, 1859, and was stolen after four days.[4] The Murats left for California on horseback, but returned to Denver with more than US$50,000 in a stagecoach. They bought a saloon, Criterion Hall, but left Colorado again in 1863 for Virginia City, Nevada, where they established the Continental Restaurant. There were other trips to Europe and California before, in later years, settling in Palmer Lake, Colorado. Their financial resources declined after 1876, and she divorced Henri in 1881. Drinking heavily, he died broke,[3] in the County Hospital in Denver.[1]

Later years, death, legacy

Countess Murat, as she was known in the pioneer days of Colorado, dependent upon herself, became a washerwoman and took in summer boarders. With her own earnings, she built a little, white frame cottage at Palmer Lake's Glen Park,[2] which was her last home.[1] She received a pension of US$10 per month from the Pioneer Ladies Aid Society,[4] in her last nineteen years.[3] By 1900, she was known to have developed rheumatism and erysipelas. Her water supply was piped to her free of charge by the town of Palmer Lake.[4]

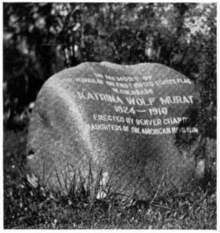

Murat was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She died on March 13, 1910,[4] and was buried near Henri in Riverside Cemetery.[5] To commemorate her services, a boulder of silver plume granite was placed on her grave, bearing the inscription:— "In memory of the maker of the first United States Flag in Colorado, Katrina Wolf Murat 1824–1910, Erected by Denver Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution."[1][4]

First United States flag in Colorado

In the winter of 1858–1859, Murat, assisted by Wapolah, a Sioux, sewed the seams of the first U.S. flag in Colorado. Murat purchased blue and white muslin ([lower-alpha 1]), but, lacking red material, cut up a red merino petticoat, which she had brought from France. Wapolah aided in sewing the stripes, while Murat arranged the placing of the stars. The significance of the flag was grasped only partially by Wapolah. She thought it applied more to the President than to the country, for she often said, while regarding it: "for the great Father at Washington." Later, Wapolah heeded the call of her own people, returned to the Dakotahs, and was lost sight of. A pole was brought from the foothills and the flag raised by means of rope and pulley, amidst a throng of spectators. Three hearty cheers ended the ceremony.[1]

Nicknamed the "Betsy Ross of Colorado",[5] when asked, in her old age, how she made the flag without a pattern, she answered:— "How could anyone who has seen that flag and loves liberty and freedom forget what it is like? I knew there must be a star for every State and I counted the States at that time. When you love America, you love the American flag."[1]

Notes

- Another account states she used part of a blue ballgown.[5]

References

- Daughters of the American Revolution 1917, p. 82-83.

- Talbot 1896, p. 250.

- Fetter 2004, p. 39-42.

- Summers, Danny (11 May 2011). "Countess Katrina Wolf Murat". Colorado Community Media. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Wommack 2005, p. 95.

Attribution

Bibliography

- Fetter, Rosemary (1 December 2004). Colorado's Legendary Lovers: Historic Scandals, Heartthrobs, and Haunting Romances. Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 978-1-938486-24-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wommack, Linda (2005). From the Grave: A Roadside Guide to Colorado's Pioneer Cemeteries. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. ISBN 978-0-87004-565-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Katrina Wolf Murat. |