Kathy Wilkes

Kathleen Vaughan Wilkes (23 June 1946 – 21 August 2003) was an English philosopher and academic who played an important part in rebuilding the education systems of former Communist countries after 1990. She established her reputation as an academic with her contributions to the philosophy of mind in two major works and many articles in professional journals. As a conscientious college tutor, she won the respect and affection of her students and academic colleagues. Her most notable contribution lay in her clandestine activities behind the Iron Curtain, which led to the establishment of underground universities and academic networks in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe. For her work in support of this network President Václav Havel awarded her the Commemorative Medal of the President of the Czech Republic in October 1998.[1]

Kathy Wilkes | |

|---|---|

| Born | 23 June 1946 |

| Died | 21 August 2003 (aged 57) |

| Education | MA Greats (Oxon); PhD in philosophy (Princeton) |

| Alma mater | St Hugh's College, Oxford, Princeton University |

| Occupation | Philosopher |

| Employer | St Hilda's College, Oxford |

| Known for | Jan Hus Educational Foundation |

| Parent(s) | John Vaughan Wilkes and Joan Alington |

| Relatives | Cyril Alington (grandfather) |

| Awards | Commemorative Medal of the President of the Czech Republic, October 1998 |

Early life and academic career

Wilkes, who was known as Kathy, was the daughter of Rev. J C Vaughan Wilkes who had been a master at Eton and Warden of Radley College before entering holy orders, and was for many years vicar of Marlow. Her paternal grandparents had founded and run St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, while her grandfather on her mother's side (the Very Rev Cyril Alington) had been Headmaster of Eton, Dean of Durham and author of many famous hymns. She was educated at Wycombe Abbey and St Hugh's College, Oxford, where she achieved a double First. Her achievement was all the greater in light of the excruciating pain she was suffering from as a result of a teenage riding accident. She spent a period at Princeton University, where she studied with Thomas Nagel, Richard Rorty and others, and received her Ph.D. She then lived the life of an Oxbridge don. After a time at King's College, Cambridge, she became a fellow of St Hilda's College, Oxford, in 1973, and was a lecturer in philosophy in the University of Oxford for the rest of her career.[2]

Work in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe: Czechoslovakia

During her time at Oxford, she worked, often in secret, for the education systems of eastern Europe. In 1979 she was the first of Oxford university's philosophers to respond to an invitation from the dissident philosophical community in Prague to conduct secret seminars there. She showed extraordinary courage in conducting secret meetings in crowded flats with groups of philosophers. Despite her large frame and ungainly walk, she would lead the secret policemen who followed her on wild goose chases through Slavic cities, unconcerned by their harassment. She made the difficult and risky trip many times, smuggling in banned books and taking out samizdat manuscripts. With her western friends, she created the Jan Hus Foundation, which was to become a major source of support for the dissident community. She encouraged and financially supported dissident intellectuals, finally bringing the Czech philosopher Julius Tomin and family to England. Having lost her Czech visa, she achieved this by returning to Prague with a new passport in her full name "Vaughan-Wilkes" to confuse the authorities. Having never driven there before, she drove the family precariously in a heavily overladen Zhiguli to the West knowing that the slightest traffic infringement would bring down the law. Back in England she arranged housing and paid for the children's education.[3]

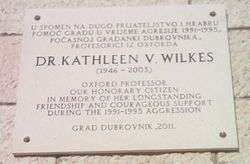

Work in the former Yugoslavia

Wilkes became Chairman of the executive committee of the Inter-University Centre in Dubrovnik in 1986. Concerned at the lack of voice for philosophers in the east who were interested in the analytic approach, with Bill Newton-Smith as her co-editor, she created a journal known initially as the Dubrovnik Papers, and now flourishing as International Studies in the Philosophy of Science. She paid for a young Croatian psychologist's education at Oxford, maintaining throughout that the fees were being met by a fictitious 'Alington trust'. During the siege of Dubrovnik by the JNA in 1991–1992 during the Croatian war of independence, she refused to leave, seeing it her duty to give comfort and support to the sufferers and to inform the world of the City's distress.

Following the collapse of their political regimes, especially that of the former Yugoslavia, she worked to try to restore their academic standards, spending time in Croatia, where she was honoured with a doctorate from the University of Zagreb.

Kathy Wilkes was specifically referenced by her colleague Roger Scruton who took her as his model of the English gentleman, arguing that "her virtues were revealed in nothing so much, as her habit of concealing them".[4] She appeared in the Channel 4 documentary series College Girls, broadcast in 2002 about some St Hilda's students.

Works

- Physicalism (1978)

- Real People (1988), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-824080-5

- Modelling the Mind (1990) editor with W. Newton Smith

References

- Day, Barbara. The Velvet Philosophers. The Claridge Press, 1999, pp. 281–282.

- Newton-Smith, Bill. "Kathy Wilkes", obituary, The Guardian, 19 September 2003.

- Day, Barbara. The Velvet philosophers. The Claridge Press, 1999.

- Roger Scruton England: an Elegy (2001)