Cajamarca

Cajamarca (Spanish pronunciation: [kaxaˈmaɾka]), also known by the Cajamarca Quechua name, Kashamarka, is the capital and largest city of the Cajamarca Region as well as an important cultural and commercial center in the northern Andes. It is located in the northern highlands of Peru at approximately 2,750 m (8,900 ft) above sea level[2] in the valley of the Mashcon river.[3] Cajamarca had an estimated population of about 226,031 inhabitants in 2015, making it the 13th largest city in Peru.[1]

Cajamarca | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Partial view of the city, Nuestra Señora de la Piedad Church, Santa Catalina Church. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

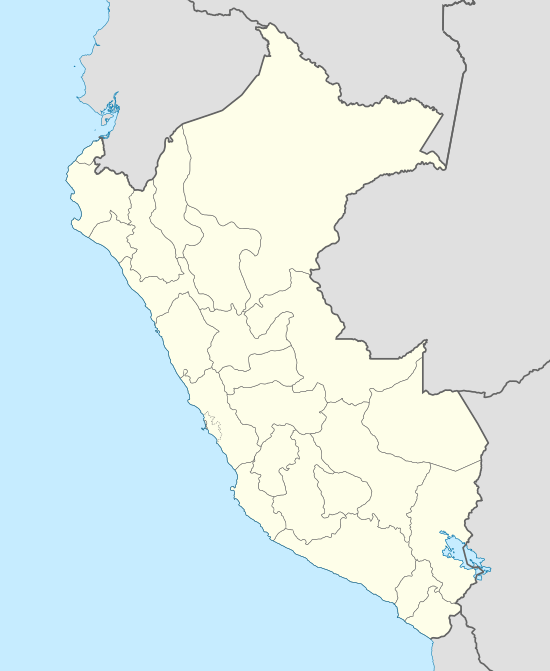

Cajamarca Location in Peru | |

| Coordinates: 07°09′52″S 78°30′38″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Cajamarca |

| Province | Cajamarca |

| Founded | c. 1320 by pre-Columbian ethnic groups Spanish settlement in 1532 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Víctor Andrés Villar Narro (2019–2022) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 392.47 km2 (151.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,750 m (9,020 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 201,329 |

| • Estimate (2015)[1] | 226,031 |

| • Density | 510/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Cajamarquino/a |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (PET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (PET) |

| Area code(s) | 76 |

| Website | municaj.gob.pe |

Cajamarca has a mild highland climate, and the area has a very fertile soil. The city is well known for its dairy products and mining activity in the surroundings.[4][5]

Among its tourist attractions, Cajamarca has numerous examples of Spanish colonial religious architecture, beautiful landscapes, pre-Hispanic archeological sites and hot springs at the nearby town of Baños del Inca (Baths of the Inca). The history of the city is highlighted by the Battle of Cajamarca, which marked the defeat of the Inca Empire by Spanish invaders as the Incan emperor Atahualpa was captured and murdered here.[6]

Etymology

The etymology of the Quechua language name Kasha Marka (Cajamarca dialect), sometimes spelled Cashamarka or Qasamarka is uncertain. It may mean 'town of thorns'.[7] Another theory suggests that it is a hybrid name that combines a Quechua kasha 'cold' and the Quechua marca 'place'.[8][9] All sources agree that the word has Quechua origin.[7][8]

History

The city and its surroundings have been occupied by several cultures for more than 2000 years. Traces of pre-Chavín cultures can be seen in nearby archaeological sites, such as Cumbe Mayo and Kuntur Wasi.

Huacaloma is an archaeological site located 3.5 km southeast of the historic center of the city of Cajamarca (currently in the middle of the Metropolitan Area of Cajamarca). Its antiquity is calculated between 1500 and 1000 BC, that is to say, it belongs to the Andean Formative Period. It presents enclosures with bonfires, similar to those of La Galgada and Kotosh, but with simpler design.[10] It was a ceremonial center where fire rituals were performed.

In 1986 the Organization of American States designated Cajamarca as a site of Historical and Cultural Heritage of the Americas.[11]

Pre-Columbian Cajamarca

The Cajamarca culture began flourishing as a culture during the first millennium AD[12]

The unbroken stylistic continuity (i.e., autonomy) of Cajamarca art from its inception around 200-100 BC up to the Spanish conquest is remarkable,[13] given the presence of powerful neighbors and the series of imperial expansions that reached this area.[13] It is known essentially only from its fine ceramics made with locally abundant white kaolin paste fired at high temperatures (over 1,000 °C).

Cajamarca culture pottery has long been recognized as a prestige ware, given its distinctiveness and wide, if sporadic, distribution. Initial Cajamarca ceramics (200 BC to AD 200) are largely confined to the Cajamarca Basin. Early Cajamarca ceramics (AD 200–450) have more complex and diverse decorations and extensive distribution. They are found in much of the North Highlands as well as in yunka zones on both the Amazonian and Pacific sides of the Andes. In fact, at least one Early Cajamarca high-prestige burial has been documented at the Moche site of San Jose de Moro (lower Jequetepeque), and a set of imported kaolin spoons has been found at the site of Moche, the city capital of the Southern Moche polity.[14]

Cajamarca ceramics achieved their greatest prestige and widest distribution during Middle Cajamarca subphase B (700-900), coinciding with Moche demise and dominance of the Wari empire in Peru.[15] Middle Cajamarca prestige ceramics have been found at a great deal of Wari sites, as far as southern-frontier Wari sites such as the city of Pikillacta located in Cusco region.[16] Moreover, the construction of the north coastal settlement of Cerro Chepen, a massive terraced mountain city-fortress in Moche territory is attributed to an apparent joint effort between Wari and Cajamarca polities to ruler over this area of Peru.

In 2004 a large building erected in Cerro Chepen mountain was excavated, said structure follows high-altitude Andean architectural models, which is tentatively interpreted as an elite residential structure. Excavations have shown an unexpected association between Late Moche domestic ceramics and fine ceramics from the Cajamarca mountains inside the patios, galleries and rooms that make up the structure. The evidence recovered in this building suggests the presence of highland officials in the heart of the Cerro Chepen Monumental Sector.[17]

However, the rise of the Middle Sican state on the north coast around 900-1000 saw a notable reduction in the distribution of Late Cajamarca ceramics back to the extent seen during Moche Phase IV.[14]

Analysis of settlement patterns in the Cajamarca Valley shows a significant reduction in the number of settlements during the Late Cajamarca phase (AD 850–1200). Scholars interpret this reduction in the number of settlements as the result of population reduction and/or dispersion, probably linked to the end of Wari influence in the region and the collapse of the EIP/MH regional polity organized around the center of Coyor in the Cajamarca Valley.[18]

With the collapse of Wari influence in the Cajamarca region the number of settlements first dropped, but then gradually increased by the Final Cajamarca phase (1250–1532). Cajamarca maintained its prestige, as shown by the influence its ceramics still had on the coast. During the Final Cajamarca phase settlements like Guzmango Viejo or Tantarica in the western slopes of the cordillera to the coast, as well as Santa Delia in the Cajamarca Valley became particularly large (> 20ha). These centers have a larger number of clearly distinguishable elite residential units as well as a greater number of fine ceramics than any earlier sites. It is clear that they are top ranked settlements in the region. At least the centers of the upper sections of the coastal valleys to the west probably benefited from their strategic location in relation first to Sican and later to Chimu. Scholars interpret the changes of the Final Cajamarca phase as evidence of a renewed prosperity and integration of the region.[19]

15th century - Inca Empire and Cuismancu Kingdom

During the period between 1463 and 1471, Ccapac Yupanqui and his nephew Tupac Inca Yupanqui, both Apuskispay-kuna or Inca generals, conquered the city of Cajamarca and brought it into the Tawantinsuyu or Inca Empire, at the time it was ruled by Tupac Inca Yupanqui's father, Pachacutiq. Nevertheless, the city of Kasha Marka had already been founded by other ethnic groups almost a century before its incorporation to the Inca empire, approximately in the year 1320.

Although Ccapac Yupanqui conquered the city of Cajamarca, the supply line was poorly made and controlled, as he traveled hastily to Cajamarca without building or conquering on much of the journey from central Peru, Ccapac Yupanqui believed Inca army's supply line of troops and supplies wasn't optimal and thus put at risk the Inca control over the newly acquired city of Cajamarca. Ccapac Yupanqui left part of his troops garrisoned at Cajamarca, and then he returned to Tawantinsuyu in order to ask for reinforcements and conducted a more extensive campaign in the territories of central Peru, building a great quantity of infrastructure (such as tambos, colcas, pukaras, etc.) along the Inca road. Incas remodeled Cajamarca following Inca canons of architecture, however, not much of it has survived since the Spanish did the same after conquering Cajamarca.

Colonial accounts tell of Cuismancu Kingdom, the historical counterpart of the Final Cajamarca archaeological culture. According to the chroniclers, Cuismanco, Guzmango or Kuismanku (modern Quechua spelling) was the political entity that ruled the Cajamarca area before the arrival of the Incas and was incorporated into the Inca dominion.

The kingdom or domain of Cuismanco belongs to the last phase of the Cajamarca Tradition and of all the nations of the northern mountains of Peru it was the one to achieve the highest social, political and cultural development.[20]

Oral tradition records their title, Guzmango Capac – Guzmango being the name of the ethnic group or polity, while Capac signified a divine ruler whose forefathers displayed a special force, energy, and wisdom in ruling. By the time the Spaniards began to ask about their history, the polity's residents (called Cajamarquinos today) could remember the names of only two brothers who had served as Guzmango Capac under the Incas.

The first was called Concacax, who was followed by Cosatongo. After Concacax died, his son, Chuptongo, was sent south to serve the emperor, Tupac Inca Yupanqui. There he received an education at court and, as a young adult, became the tutor of one of Inca Yupanqui's sons, Guayna Capac. Oral history records that "he gained great fame and reputation in all the kingdom for his quality and admirable customs". It was also said that Guayna Capac respected Chuptongo as he would a father. Eventually, Tupac Inca Yupanqui named Chuptongo a governor of the empire.

When Guayna Capac succeeded his father as Sapan Inka, Chuptongo accompanied the new sovereign to Quito for the northern campaigns. After years of service, he asked Guayna Capac to allow him to return to his native people. His wish was granted; and, as a sign of his esteem, Guayna Capac made him a gift of one hundred women, one of the highest rewards possible in the Inca empire. In this way, Chuptongo established his house and lineage in the old town of Guzmango, fathered many children, and served as paramount lord until his death.

The struggle for the throne between the two half brothers Huascar and Atahualpa, sons of Guayna Capac, also divided the sons of Chuptongo. During the civil war that broke out after Guayna Capac's death, Caruatongo, the oldest of Chuptongo's sons, sided with the northern forces of Atahualpa, while another son, Caruarayco, allied with Huascar, ruler of the south faction.

In 1532 Atahualpa defeated his brother Huáscar in a battle for the Inca throne in Quito (in present-day Ecuador). On his way to Cusco to claim the throne with his army, he stopped at Cajamarca.[21]:146–149

Capture of Atahualpa (1532 A.D.); Colonial period

After arriving to Cajamarca, Francisco Pizarro received news that Atahualpa was resting in Pultumarca, a nearby hot springs complex, Pizarro soon sent some of representatives under command of the young captain Hernando De Soto to invite the Inca to a feast.

After arriving at Atahualpa's camp, Hernando de Soto interviewed with Atahualpa. The Inca Emperor was seated on his gold throne or usnu, with two of his concubines on both sides holding a veil that made only his silhouette recognizable. Atahualpa, impressed by the Spanish horses, asked Hernando de Soto to do an equestrian demonstration. In the final act of his demonstration, Hernando De Soto rode on horseback directly up to Atahualpa to intimidate him stopping at the last moment,[22] however Atahualpa did not move or change his expression in the slightest.[23] Nevertheless, some of Atahualpa's retainers drew back and for it they were executed that day, after the Spanish committee returned to Cajamarca.

Atahualpa agreed to meet with Pizarro the next day, oblivious of the ploy Pizarro had prepared for him. The following day, Atahualpa arrives in procession with his court and soldiers, although unarmed, Spanish accounts tell of the splendor shown by Atahulpa's display, in addition to musicians and dancers, Indians covered the Inca road on which their king would travel with hundreds of colorful flower petals, moreover, Atahualpa's retainers marched unison without speaking a word.

Several noble leaders from conquered nations were also present, mostly local kuraka-kuna from the towns nearby, however, there were also notable Tawantinsuyu's nobles among them, there were the prominent rulers known as the "Lord of Cajamarca" and the "Lord of Chicha", both descendants of kings and owners of huge accumulations of wealth and lands in the Inca Empire, each one accompanied with its own sumptuous court, moreover, both were carried on litters in the same manner of Atahualpa. The Lord of Chicha's court was so opulent, even more than Atahualpa's, that the Spanish, most of them who did not meet Atahualpa until then, at first thought the Lord of Chicha was the Inca Emperor.[24]

Pizarro and his 168 soldiers met Atahualpa in the Cajamarca plaza after weeks of marching from Piura. The Spanish Conquistadors and their Indian allies captured Atahualpa in the Battle of Cajamarca, where they also massacred several thousand unarmed Inca civilians and soldiers in an audacious surprise attack of cannon, cavalry, lances and swords. The rest of the army of 40,000–80,000 (Conquistadors' estimates) was stationed some kilometers away from Cajamarca in a large military camp, near the Inca resort town of Pultamarca (currently known as "Baños del Inca"), with its thousands of tents as looking from afar "like a very beautiful and well-ordered city, because everyone had his own tent".

Having taken Atahualpa captive, they held him in Cajamarca's main temple. Atahualpa offered his captors a ransom for his freedom: a room filled with gold and silver (possibly the place now known as El Cuarto del Rescate or "The Ransom Room"), within two months. Although having complied with the offering, Atahualpa was brought to trial and executed by the Spaniards. the Pizarros, Almagro, Candia, De Soto, Estete, and many others shared in the ransom.

Caruatongo, the "Lord of Cajamarca", who was privileged enough to have been carried into the plaza of Cajamarca on a litter, a sure sign of the Inca's favor, died there on 16 November 1532, when Francisco Pizarro and his followers ambushed and killed many of the emperor's retainers and captured the Inca, Atahualpa. Although Caruatongo left an heir (named Alonso Chuplingon, after his Christian baptism), his brother, Caruarayco, succeeded him as headman following local customs. Pizarro himself recognized Caruarayco and confirmed his right to assume the authority of his father. Caruarayco took the name Felipe at his baptism, becoming the first Christian kuraka of Cajamarca. He remained a steadfast ally of the Spaniards during his lifetime, helping to convince the lords of the Chachapoyas people to submit to Spanish rule. Felipe Caruarayco was paramount lord of the people of Guzmango, in the province of Cajamarca, under the authority of the Spaniard, Melchior Verdugo. Pizarro had awarded Verdugo an encomienda in the region in 1 535. Documentation from that year described Felipe as the cacique principal of the province of Cajamarca and lord of Chuquimango, one of seven large lineages or guarangas (an administrative unit of one thousand households) that made up the polity. By 1543, however, Felipe was old and sick. His son, don Melchior Caruarayco, whom he favored to succeed him, was still too young to rule, so two relatives were designated as interim governors or regents: don Diego Zublian and don Pedro Angasnapon. Zublian kept this position until death in 1560, and then don Pedro appropriated for himself the title "cacique principal of the seven guarangas of Cajamarca", remaining in office until his death two years later. After his death, the people of Cajamarca asked the corregidor, don Pedro Juares de Illanez, to name don Melchior as their kuraka. After soliciting information from community elders, Illanez named him "natural lord and cacique principal of the seven guarangas of Cajamarca". As the paramount Andean lord of Cajamarca, don Melchior was responsible for the guaranga of Guzmango and two more parcialidades (lineages or other groupings of a larger community): Colquemarca (later Espiritu Santo de Chuquimango) and Malcaden (later San Lorenzo de Malcadan. This charge involved approximately five thousand adult males, under various lesser caciques; and, counting their families, the total population that he ruled approached fifty thousand. Most of these mountain people, who lived dispersed in more than five hundred small settlements, subsisted by farming and by herding llamas. Their tribute responsibilities included rotating labor service at the nearby silver mines of Chilete. During one of his many long trips down from the highlands to visit the nearest Spanish city, Trujillo, don Melchior was stricken by a serious illness. He prudently dictated his last will and testament before the local Spanish notary, Juan de Mata, on 20 June 1565. Coming as he did from a relatively remote area where very few Spaniards resided, his will reflects traditional Andean conceptions of society and values before they were fundamentally and forever changed. This is evident in the care he took to list all of his retainers. He claimed ten potters in the place of Cajamarca, a mayordomo or overseer from the parcialidad of Lord Santiago, a retainer from the parcialidad of don Francisco Angasnapon, and a beekeeper who lived near a river. In the town of Chulaquys, his followers included a lesser lord (mandoncillo) with jurisdiction over seven native families. At the mines of Chilete, he listed twenty workers who served him. Don Melchior also claimed six servants with no specific residence and at least twenty-four corn farmers and twenty- two pages in the town of Contumasa. Nine different subjects cared for his chili peppers and corn either in Cascas or near the town of Junba (now Santa Ana de Cimba?). He also listed the towns of Gironbi and Guaento, whose inhabitants guarded his coca and chili peppers; Cunchamalca, whose householders took care of his corn; and another town called Churcan de Cayanbi. Finally, he mentioned two towns that he was disputing with a native lord whose Christian name was don Pedro. In total, don Melchior claimed jurisdiction over a minimum of 102 followers and six towns, including the two in dispute. This preoccupation of don Melchior with listing all of his retainers shows how strong Andean traditions remained in the Cajamarca region, even thirty years after the Spanish invasion. Among the indigenous peoples, numbers of followers denoted tangible wealth and power. An Andean chronicler, Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, wrote that lords "will gain rank if the numbers [of their subjects] multiply according to the law of the dominion over Indians. And, if their numbers decline, they too lose [status]". This concept of status was the same one held in the Inca system. The hatun curaca or huno apo, lord of ten thousand households, ranked higher than a guaranga curaca, the lord of one thousand. The latter dominated the lord of one hundred Indians, a pachaca camachicoc, who in turn was superior to the overseers (mandones and mandoncillos) with responsibility for as few as five households. Don Melchior, as a chief of seven guarangas, had jurisdiction over other lesser lords, who themselves ruled individual lineages.[25]

Geography

Cajamarca is situated at 2750 m (8900 ft) above sea level on an inter-Andean valley irrigated by three main rivers: Mashcon, San Lucas and Chonta; the former two join together in this area to form the Cajamarca river.[26]

Cityscape

Architecture

The style of ecclesiastical architecture in the city differs from other Peruvian cities due to the geographic and climatic conditions. Cajamarca is further north with a milder climate; the colonial builders used available stone rather than the clay of used in the coastal desert cities.

Cajamarca has six Christian churches of Spanish colonial style: San Jose, La Recoleta, La Immaculada Concepcion, San Antonio, the Cathedral and El Belen. Although all were built in the seventeenth century, the latter three are the most outstanding due to their sculpted facades and ornamentation.

The facades of these three churches were left unfinished, most likely due to lack of funds. The façade of the Cathedral is the most elegantly decorated, to the extent that it was completed. El Belen has a completed façade of the main building, but the tower is half finished. The San Antonio church was left mostly incomplete.[27][28]

Church of Belen

This church consists of a single nave with no lateral chapels. Its facade is the most complete of the three, as it was the first to be designed and built.[27][28]

Cathedral of Cajamarca

Originally designated to be a parish church, the cathedral took 80 years to construct (1682–1762); the façade remains unfinished. The Cathedral shows how colonial Spanish influence was introduced in the Incan territory.

Side Portals: The side portals are made of pilasters on corbels. It also bears the royal escutcheon of Spain. The portal is considered to have a seventeenth-century character, found in the rectangular emphasis of the design.

Plan: The plan of the cathedral is based on a basilica plan, (with a single apse, barrel vaults in the nave, a transept and sanctuary), but the traditional dome over the crossing has been omitted.

Façade: The façade is noted for the detailing of its sculptures and the artistry in carving. Decorative details include grapevines carved into the spiral columns of the cathedral, with little birds pecking at the grapes. The frieze in the first story is composed of rectangular blocks carved with leaves. The detail of the main portal extends to flower pots and cherubs' heads next to pomegranates. "The façade of Cajamarca Cathedral is one of the remarkable achievements of Latin American art."[27][28]

San Antonio

Construction began in 1699, with the original plans made by Matias Perez Palomino. This church is similar in plan to the Cathedral, but the interiors are quite different. San Antonio is a significantly larger structure and has incorporated the large dome over the crossing. Features of the church include large cruciform piers with Doric pilasters, a plain cornice, and stone carved window frames.

Façade: This façade is the most incomplete. While designed in a style similar to that of the cathedral, it is a simplified version.[27][28]

Climate

Cajamarca has a subtropical highland climate (Cwb, in the Köppen climate classification) which is characteristic of high elevations at tropical latitudes. This city presents a semi-dry, temperate, semi-cold climate with presence of rainfall mostly on spring and summer (from October to March) with little or no rainfall the rest of the year.

| Climate data for Cajamarca | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3.1 (37.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5 (41) |

6.2 (43.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

5.3 (41.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 83.9 (3.30) |

96.4 (3.80) |

110.3 (4.34) |

80.3 (3.16) |

34.6 (1.36) |

7 (0.3) |

6.3 (0.25) |

11.3 (0.44) |

32.8 (1.29) |

81.9 (3.22) |

73.2 (2.88) |

72.6 (2.86) |

690.6 (27.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 13 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 11 | 115 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67 | 67 | 72 | 69 | 64 | 58 | 55 | 55 | 57 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 63 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (precipitation days and humidity 1931–1960)[30] | |||||||||||||

Daily average temperatures have a great variation, being pleasant during the day but cold during the night and dawn.[31] January is the warmest month, with an average maximum temperature of 72 °F (22 °C) and an average minimum of 45 °F (7 °C). The coldest months are June and July, both with an average maximum of 71 °F (21 °C) but with an average minimum of 38 °F (3 °C).[32] Frosts may occur but are less frequent and less intense than in the southern Peruvian Andes.[3]

Demographics

In recent years, the city has experienced a high rate of immigration from other provinces in the region and elsewhere in Peru, mainly due to the mining boom. This phenomenon has caused the city's population to increase considerably, from an estimated 80,931 in 1981 to an estimated 283,767 in 2014, an increase of almost three times the population for 33 years. Likewise, the city has recently entered into a conurbation process with the town of Baños del Inca (which by 2014 has more than 20,000 inhabitants in the urban area) and with some populated centers close to these cities. According to INEI, projections exist for the urban conglomerate to reach 500,000 inhabitants by 2030.

Economy

Cajamarca is surrounded by a fertile valley, which makes this city an important center of trade of agricultural goods. Its most renowned industry is that of dairy products.[4][5] Yanacocha is an active gold mining site 45 km north of Cajamarca, which has boosted the economy of the city since the 1990s.[33][34]

Transportation

The only airport in Cajamarca is Armando Revoredo Airport located 3.26 km northeast of the main square. Cajamarca is connected to other northern Peruvian cities by bus transport companies.

The construction of a railway has been proposed to connect mining areas in the region to a harbor in the Pacific Ocean.[35]

Education

Cajamarca is home of one of the oldest high schools in Peru: San Ramon School, founded in 1831.[36] Some of the largest, most important schools in the city include Marcelino Champagnat School, Cristo Rey School, Santa Teresita School, and Juan XXIII School.

Cajamarca is also a centre of higher education in the northern Peruvian Andes. The city hosts two local universities: Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca (National University of Cajamarca), a public university, while Universidad Antonio Guillermo Urrelo is a private one.[37] Five other universities have branches in Cajamarca: Universidad Antenor Orrego,[38] Universidad San Pedro,[39] Universidad Alas Peruanas,[40] Universidad Los Angeles de Chimbote[41] and Universidad Privada del Norte.[42]

Culture

Cajamarca is home to the annual celebration of Carnaval, a time when the locals celebrate Carnival before the beginning of Lent. Carnival celebrations are full of parades, autochthonous dances and other cultural activities. A local Carnival custom is to spill water and/or some paint among friends or bypassers. During late January and early February this turns into an all-out water war between men and women (mostly between the ages of 6 and 25) who use buckets of water and water balloons to douse members of the opposite sex. Stores everywhere carry packs of water balloons during this time, and it is common to see wet spots on the pavement and groups of young people on the streets looking for "targets".

Notable people from Cajamarca

- Carlos Castaneda:(1925-1998) Author and anthropologist.

- es:Lorenzo Iglesias:(1844-1885) Independence hero.

- Mariano Ibérico Rodríguez:(1892-1974) Philosopher.

- es:Rafael Hoyos Rubio:(1924-1981) General.

- Fernando Silva Santisteban:(1929–2006) Anthropologist.

- Andrés Zevallos de la Puente:(1916-2017) Painter.

- Mario Urteaga Alvarado:(1875-1957) Painter.

- es:Camilo Blas (José Alfonso Sánchez Urteaga):(1903-1985) Painter, and member of the "Grupo Norte" intellectual community of Peru.

- Amalia Puga de Losada:(1866-1963) Writer and poetess.

- es:José Gálvez Egúsquiza:(1819-1866) War hero from the "Combate del 2 de mayo".

- es:Toribio Casanova:(1926-1867) Founder of the Cajamarca region.

- es:Aurelio Sousa y Matute:(1860-1925) Politician who served as minister, deputy and senator.

References

- Perú: Estimaciones y Proyecciones de Población Total por Sexo de las Principales Ciudades, 2000 – 2015 (in Spanish). Lima: INEI. 2012. p. 17.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 June 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Tourist Climate Guide. SENAMHI. 2008. p. 55.

- "Mantecoso Cheese in Peru". Publications.cirad.fr. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- "Cajamarca, Peru". Planeta.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- "Battle of Cajamarca: Pizarro's Conquistadores Ambush, Capture Incan Emperor". The American Legion's Burnpit. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Sarmiento, Julio; Ravines, Tristán (1993). Cajamarca: Historia y Cultura. Instituto Andino de Artes Populares.

- "Reseña Histórica". Municipalidad Provincial de Cajamarca. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- Everett-Heath, John (13 September 2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192562432.

- Rosenfeld, Silvana; Bautista, Stefanie (15 March 2017). Rituals of the Past: Prehispanic and Colonial Case Studies in Andean Archaeology. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9781607325963.

- "Proceedings Volume I" (PDF). Organization of American States – General Assembly. 17 December 1986. p. 19. Retrieved 16 December 2015. (Ag/Res. 810 (XVI-0/86))

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (5 November 2013). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. ISBN 9781134259304.

- Salomon, Frank; Schwartz, Stuart B. (28 December 1999). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521630757.

- Salomon, Frank; Schwartz, Stuart B. (1999). South America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521333931.

- Salomon, Frank; Schwartz, Stuart B. (December 1999). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas edited by Frank Salomon. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521630757. ISBN 9781139053785.

- Bauer, Brian S. (28 June 2010). Ancient Cuzco: Heartland of the Inca. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292792029.

- Rosas Rintel, Marco (1 August 2007). "Nuevas perspectivas acerca del colapso Moche en el Bajo Jequetepeque. Resultados preliminares de la segunda campaña de investigación del proyecto arqueológico Cerro Chepén". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines (in Spanish). 36 (2): 221–240. doi:10.4000/bifea.3835. ISSN 0303-7495.

- Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (6 April 2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387749075.

- Quilter, Jeffrey (17 December 2013). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge. ISBN 9781317935247.

- Santisteban, Fernando Silva (2001). Cajamarca, historia y paisaje. BPR Publishers. ISBN 9789972828027.

- Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. Mc Graw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 6

- Crow, John A. (17 January 1992). The Epic of Latin America, Fourth Edition. University of California Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780520077232.

Several of the Incas drew back in terror, but Atahualpa did not budge an inch or change his expression in the slightest.

- Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture: 2. Scribner. 1996. ISBN 9780684197531.

- Andrien, Kenneth J. (2 May 2013). The Human Tradition in Colonial Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442213005.

- "Datos Generales". CajamarcaPeru.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Harold E. Wethey, Colonial Architecture and Sculpture in Peru (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1949), 129–139

- Damian Bayon and Murillo Marx, History of South American Colonial Art and Architecture (New York: Rizzoli Publications, 1992)

- "World Weather Information Service (World Meteorological Organization)". Worldweather.wmo.int. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Peru – Cajamarca" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Tourist Climate Guide. SENAMHI. 2008. p. 57.

- "World Weather Information Service". World Weather Information Service. World Weather Organization. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "FERROCARRIL NORANDINA RAILROAD STARTS ITS JOURNEY COMING FEBRUARY". Minerandina.com. 10 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego". 12 July 2007. Archived from the original on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "UAP – Filial Cajamarca". Uap.edu.pe. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Nuestras sedes". Upn.edu.pe. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

Further reading

- Conquest of the Incas. John Hemming, 1973.

External links

- Cajamarca map

- Cajamarca information, photos and travel

- Miracle Village International a charity that works in Cajamarca with

- Villa Milagro

- Davy College

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cajamarca. |