Kano model

The Kano model is a theory for product development and customer satisfaction developed in the 1980s by Professor Noriaki Kano, which classifies customer preferences into five categories.

Categories

These categories have been translated into English using various names (delighters/exciters, satisfiers, dissatisfiers, etc.), but all refer to the original articles written by Kano.

- Must-be Quality

- Simply stated, these are the requirements that the customers expect and are taken for granted. When done well, customers are just neutral, but when done poorly, customers are very dissatisfied. Kano originally called these “Must-be’s” because they are the requirements that must be included and are the price of entry into a market.

- Examples: In a hotel, providing a clean room is a basic necessity. In a call center, greeting customers is a basic necessity.

- One-dimensional Quality

- These attributes result in satisfaction when fulfilled and dissatisfaction when not fulfilled. These are attributes that are spoken and the ones in which companies compete. An example of this would be a milk package that is said to have ten percent more milk for the same price will result in customer satisfaction, but if it only contains six percent then the customer will feel misled and it will lead to dissatisfaction.

- Examples: Time taken to resolve a customer's issue in a call center. Waiting service at a hotel.

- Attractive Quality

- These attributes provide satisfaction when achieved fully, but do not cause dissatisfaction when not fulfilled. These are attributes that are not normally expected, for example, a thermometer on a package of milk showing the temperature of the milk. Since these types of attributes of quality unexpectedly delight customers, they are often unspoken.

- Examples: In a callcenter, providing special offers and compensations to customers or the proactive escalation and instant resolution of their issue is an attractive feature. In a hotel, providing free food is an attractive feature.

- Indifferent Quality

- These attributes refer to aspects that are neither good nor bad, and they do not result in either customer satisfaction or customer dissatisfaction. For example, thickness of the wax coating on a milk carton. This might be key to the design and manufacturing of the carton, but consumers are not even aware of the distinction. It is interesting to identify these attributes in the product in order to suppress them and therefore diminish production costs.

- Examples: In a callcenter, highly polite speaking and very prompt responses might not be necessary to satisfy customers and might not be appreciated by them. The same applies to hotels.

- Reverse Quality

- These attributes refer to a high degree of achievement resulting in dissatisfaction and to the fact that not all customers are alike. For example, some customers prefer high-tech products, while others prefer the basic model of a product and will be dissatisfied if a product has too many extra features.[1]

- Examples: In a callcenter, using a lot of jargon, using excessive pleasantries, or using excessive scripts while talking to customers might be off-putting for them. In a hotel, producing elaborate photographs of the facilities that set high expectations which are then not satisfied upon visiting can dissatisfy the customers.

| Author(s) | Driver type 1 | Driver type 2 | Driver type 3 | Driver type 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herzberg et al. (1959)[3] | Hygiene | Motivator | ||

| Kano (1984)[4] | Must-be | Attractive | One-dimensional | Indifferent |

| Cadotte and Turgeon (1988)[5] | Dissatisfier | Satisfier | Critical | Neutral |

| Brandt (1988)[6] | Minimum requirement | Value enhancing | Hybrid | Unimportant as determinant |

| Venkitaraman and Jaworski (1993)[7] | Flat | Value-added | Key | Low |

| Brandt and Scharioth (1998)[8] | Basic | Attractive | One-dimensional | Low impact |

| Llosa (1997,[9] 1999[10]) | Basic | Plus | Key | Secondary |

| Chitturi et al., (2008)[11] | Hedonic | Utilitarian |

Must-be Quality

One of the main points of assessment in the Kano model is the threshold attributes. These are basically the features that the product must have in order to meet customer demands. If this attribute is overlooked, the product is simply incomplete. If a new product is not examined using the threshold aspects, it may not be possible to enter the market. This is the first and most important characteristic of the Kano model.[12] The product is being manufactured for some type of consumer base, and therefore this must be a crucial part of product innovation. Threshold attributes are simple components to a product. However, if they are not available, the product will soon leave the market due to dissatisfaction. The attribute is either there or not. An example of a threshold attribute would be a steering wheel in a car. The car is no good if it is not able to be steered.[13]

The threshold attributes are most often seen as a price of entry. Many products have threshold attributes that are overlooked. Since this component of the product is a necessary guideline, many consumers do not judge how advanced a particular feature is. Therefore, many times companies will want to improve the other attributes because consumers remain neutral to changes in the threshold section.[14]

One-dimensional Quality

A performance attribute is defined as a skill, knowledge, ability, or behavioural characteristic that is associated with job performance. Performance attributes are metrics on which a company bases its business aspirations. They have an explicit purpose. Companies prioritise their investments, decisions, and efforts and explain their strategies using performance attributes. These strategies can sometimes be recognised through the company's slogans. For example Lexus's slogan is "The Pursuit of Perfection" (Quality) and Walmart; "Always low prices. Always" (Cost). In retail the focus is generally on assuring availability of products at best cost.

Performance attributes are those for which more is better, and a better performance attribute will improve customer satisfaction. Conversely, a weak performance attribute reduces customer satisfaction. When customers discuss their needs, these needs will fall into the performance attributes category. Then these attributes will form the weighted needs against the product concepts that are being evaluated. The price a customer is willing to pay for a product is closely tied to performance attributes. So the higher the performance attribute, the higher the customers will be willing to pay for the product.

Performance attributes also often require a trade-off analysis against cost. As customers start to rate attributes as more and more important, the company has to ask itself, "how much extra they would be willing to pay for this attribute?" And "will the increase in the price for the product for this attribute deter customers from purchasing it." Prioritization matrices can be useful in determining which attributes would provide the greatest returns on customer satisfaction.[15]

Attractive Quality

Not only does the Kano model feature performance attributes, but additionally incorporates an "excitement" attribute, as well. Excitement attributes are for the most part unforeseen by the client but may yield paramount satisfaction. Having excitement attributes can only help you, but in some scenarios it is okay to not have them included. The beauty behind an excitement attribute is to spur a potential consumer's imagination, these attributes are used to help the customer discover needs that they've never thought about before.[16] The key behind the Kano model is for the engineer to discover this "unknown need" and enlighten the consumer, to sort of engage that "awe effect." Having concurrent excitement attributes within a product can provide a significant competitive advantage over a rival. In a diverse product assortment, the excitement attributes act as the WOW factors and trigger impulsive wants and needs in the mind of the customer. The more the customer thinks about these amazing new ideas, the more they want it.[17] Out of all the attributes introduced in the Kano model, the excitement ones are the most powerful and have the potential to lead to the highest gross profit margins. Innovation is undisputedly the catalyst in delivering these attributes to customers; you need to be able to distinguish what is an excitement today, because tomorrow it becomes a known feature and the day after it is used throughout the whole world.[18]

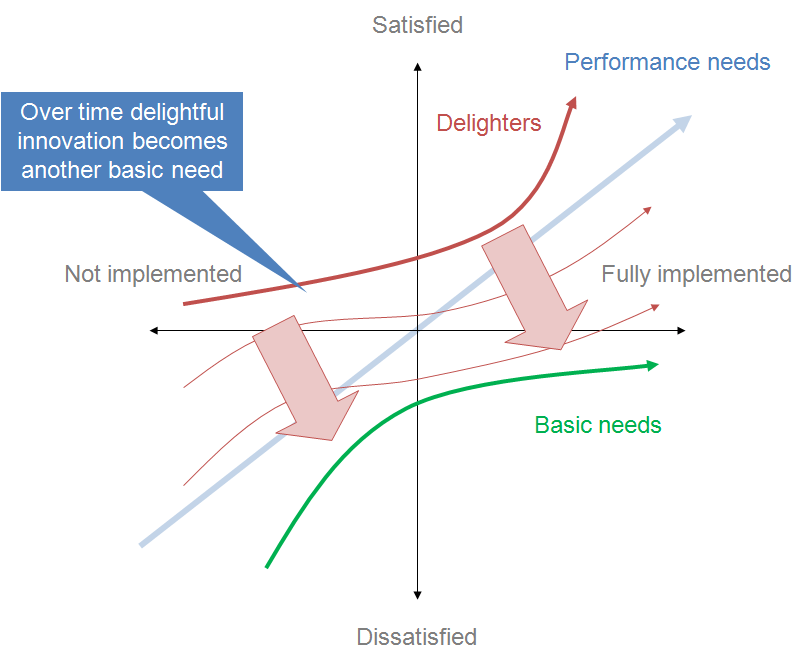

Attributes' place on the model changes over time

An attribute will drift over time from Exciting to performance and then to essential. The drift is driven by customer expectations and by the level of performance from competing products.

For example mobile phone batteries were originally large and bulky with only a few hours of charge. Over time we have come to expect 12+ hours of battery life on slim lightweight phones. The battery attributes have had to change to keep up with customer expectations.

Empirical measurement

Kano proposes a standardized questionnaire to measure participants' opinions in an implicit way. The participants therefore need to answer two questions for each product feature, from which one is "functional" (formulated in a positive way) and one is "dysfunctional" (formulated in a negative way).

Example

| I like it | I expect it | I am neutral | I can tolerate it | I dislike it | |

| Functional | |||||

| How would you feel if the product had …? | |||||

| How would you feel if there was more of …? | |||||

| Dysfunctional | |||||

| How would you feel if the product did not have …? | |||||

| How would you feel if there was less of …? | |||||

Evaluation

Based on the combination of answers by one participant for the functional and dysfunctional questions, one can infer the feature category.

| Functional | Dysfunctional | Category | ||

| I expect it | + | I dislike it | → | Must-be |

| I like it | + | I dislike it | → | One-dimensional |

| I like it | + | I am neutral | → | Attractive |

| I am neutral | + | I am neutral | → | Indifferent |

| I dislike it | + | I expect it | → | Reverse |

Illogical answers (e.g., "I like it" for both the functional and dysfunctional questions) are usually neglected or put in a special category "Questionable". Various approaches for the aggregation of categories across multiple participants have been proposed, from which the most common ones are the "Discrete analysis" and "Continuous analysis" [19].

Tools

The data for the Kano model typically is collected via a standardized questionnaire. The questionnaire can be on paper, collected in an interview, or conducted in an online survey. For the latter, general online survey software can be used, while there also are dedicated online tools specialized in the Kano model and its analysis[20][21].

Uses

Quality function deployment (QFD) makes use of the Kano model in terms of the structuring of the comprehensive QFD matrices. Mixing Kano types in QFD matrices can lead to distortions in the customer weighting of product characteristics. For instance, mixing Must-Be product characteristics—such as cost, reliability, workmanship, safety, and technologies used in the product—in the initial House of Quality will usually result in completely filled rows and columns with high correlation values. Other Comprehensive QFD techniques using additional matrices are used to avoid such issues. Kano's model provides the insights into the dynamics of customer preferences to understand these methodology dynamics.

The Kano model offers some insight into the product attributes which are perceived to be important to customers. The purpose of the tool is to support product specification and discussion through better development of team understanding. Kano's model focuses on differentiating product features, as opposed to focusing initially on customer needs. Kano also produced a methodology for mapping consumer responses to questionnaires onto his model.

See also

- Product management

- Product portfolio

- New product development

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bartikowski, B., Llosa, S. (2003). Identifying Satisfiers, Dissatisfiers, Criticals and Neutrals in Customer Satisfaction. Working Paper n° 05-2003, Mai 2003. Euromed - Ecole de Management. Marseille.

- Herzberg, Frederick; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B.B. (1959). The motivation to work (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-37390-2.

- Kano, Noriaki; Nobuhiku Seraku; Fumio Takahashi; Shinichi Tsuji (April 1984). "Attractive quality and must-be quality". Journal of the Japanese Society for Quality Control (in Japanese). 14 (2): 39–48. ISSN 0386-8230. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011.

- Cadotte, Ernest R.; Turgeon, Normand (1988). Dissatisfiers and satisfiers: suggestions from consumer complaints and compliments (PDF). Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior. 1. pp. 74–79. ISBN 978-0-922279-01-2. ISSN 0899-8620. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011.

- Brandt, D. Randall (1988). "How service marketers can identify value-enhancing service elements". Journal of Services Marketing. 2 (3): 35–41. doi:10.1108/eb024732. ISSN 0887-6045.

- Venkitaraman, R.K, Jaworski, C. (1993), Restructuring customer satisfaction measurement for better resource allocation decisions: an integrated approach, Fourth Annual Advanced Research Techniques Forum of the American Marketing Association, June.

- Brandt, D.R., Scharioth, J. (1998), Attribute life cycle analysis. Alternatives to the Kanomethod, in 51. ESOMAR-Congress, pp. 413-429.

- Llosa, S. (1997). "L'analyse de la contribution des éléments du service à la satisfaction: Un modèle tétraclasse". Décisions Marketing. 10 (3): 81–88. ISSN 1253-0476.

- Llosa, S. (1999), Contributions to the study of satisfaction in services, AMA SERVSIG Service Research Conference 10–12 April, New Orleans, pp.121-123

- Chitturi, Ravindra; Raghunathan, Rajagopal; Mahajan, Vijay (2008). "Delight by Design: The Role of Hedonic versus Utilitarian Benefits". Journal of Marketing. 72 (3): 48–63. doi:10.1509/jmkg.72.3.048. ISSN 0022-2429.

- Jacobs, Randy (1999). "Evaluating Satisfaction with Media Products and Services: An Attribute Based Approach". European Media Management Review.

- Ullman, David G. (1997). The Mechanical Design Process. McGraw-Hill. pp. 105–108. ISBN 978-0-07-065756-4.

- Bonacorsi, Steven. "Kano Model and Critical To Quality Tree." Six Sigma and Lean Resources - Home. Web. 26 April 2010.

- http://www.scortalk.com/talks/2008/01/15/performance-attributes/%5B%5D

- B.V., ©2008 12manage. "Kano's Customer Satisfaction Model - Knowledge Center".

- The Kano Model Illustrated Report

- Malcolm, Eric (6 July 2015). "FAQs about the Kano Model Customer Satisfaction Tool".

- "Analyzing a Kano study with the discrete and continuous analysis". 3 January 2020.

- "kano.plus". 3 January 2020.

- "KanoSurveys.com". 31 May 2020.

Further reading

- Cohen, Lou (1995). Quality function deployment : How to make QFD work for you. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-63330-6.

- ReVelle, Jack B.; John W Moran; Charles A Cox (1998). The QFD handbook. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-17381-6.