Kandarodai

Kandarodai (Tamil: கந்தரோடை, romanized: Kantarōṭai, Sinhala: කදුරුගොඩ, romanized: Kadurugoḍa, also known as Tamil: கதிரமலை, romanized: Katiramalai) is a small hamlet and archaeological site of Chunnakam town, a suburb in Jaffna District, Sri Lanka.

Known as Kadiramalai in the ancient period, the area served as a famous emporium city and capital of Tamil kingdoms in the Jaffna peninsula of North Eastern Ceylon from classical antiquity. The notable ancient Buddhist monastery referred as Kadurugoda Vihara is situated in Kandarodai.[1]

Located near a world-famous port at that time, Kandarodai was the first site the Archaeology Department in Sri Lanka excavated in the Jaffna peninsula.[2]

Etymology

According to Jaffna tradition was this place initially known as Kadiramalai.[3][4] According to C. Rasanayagam is the Sinhalese name Kadurugoḍa derived from Kadiragoda, which is according to him derived from Kadiramalai, substituting the Tamil suffix malai (meaning "mountain") with the Sinhalese suffix goḍa. The prefix Kadira is the Tamil name for the Acacia chundra tree.[3] The modern Tamil name Kantarōṭai is believed to be re-derived from the Kadiragoda term.[5] The Tamil name was Kadiramalai.

Some scholars holds that Kadurugoda is derived from the Sinhalese name Kandavurugoda (a site of a military encampment).[6] The Portuguese archives refer to this place as Kandarcudde.[7] The name Kadurogoda viharaya is mentioned in the 15th century Sinhalese text Nampota.[8][9]

History

In 1970, the University of Pennsylvania museum team excavated a ceramic sequence remarkably similar to that of Arikamedu in Tamil Nadu, with a Pre-rouletted ware period, subdivided into an earlier "Megalithic", a later "Pre-rouletted ware phase," followed by a "Rouletted ware period". Tentatively assigned to the fourth century BCE, radio carbon dating later confirmed an outer date of the ceramics and Megalithic cultural commencement in Kandarodai to 1300 BCE.[10][11] During this excavation, the university team discovered a potsherd carrying a Sinhalese Prakrit inscription written in Brahmi scripts.[12][note 1]

Further excavations were conducted at the site by the University of Jaffna.

Black and red ware Kanterodai potsherd with Tamil Brahmi[13]scripts from 300 BCE excavated with Roman coins, early Pandyan coins, early Chera Dynasty coins from the emporium Karur punch-marked with images of the Hindu Goddess Lakshmi from 500 BCE, punch-marked coins called Puranas from 6th-5th century BCE India, and copper kohl sticks similar to those used by the Egyptians found in Uchhapannai, Kandarodai indicate active transoceanic maritime trade between ancient Jaffna Tamils and other continental kingdoms in the prehistoric period.[14][15]

The parallel third century BCE discoveries of Manthai, Anaikoddai and Vallipuram detail the arrival of a megalithic culture in Jaffna long before the Buddhist-Christian era and the emergence of rudimentary settlements that continued into early historic times marked by urbanization.[16] Some scholars have identified Kourola mentioned by 2nd century AD Greek geographer Ptolemy and Kamara mentioned by the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea as being Kadiramalai.[17]

The earliest people of Jaffna were belonging to a megalithic culture akin to the South Indian megalithic culture. The period of Buddhism in the Jaffna Peninsula differ from the rest of the island, which is seen as an overlapping of the megalithic beliefs with Buddhism.[18] According to scholars was Kantarodai, known in Tamil literature as Kadiramalai, the capital of the ancient Tamil Kingdom ruled by Tamil speaking Naga kings from 7th century AD to 10th century AD.[4] The Yalpana Vaipava Malai also describes Kadiramalai as the seat of Ukkirasinghan who fell in love with a Chola princess in the ancient period.[19] The ancient Kadurugoda Vihara Buddhist monastery is situated at this site where a 10th century pillar inscription of Sinhalese language recording a regal proclamation of the bequest of gifts and benefits to a Buddhist place of worship was found.[1][9][12] Kandarodai was a Buddhist mercantile centre among Tamils.[20]

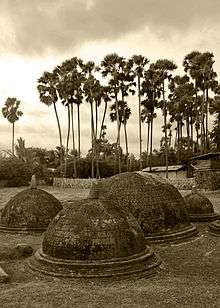

The domes were reconstructed atop the flat bases of the ruins by the Archaeology Department. The similarities between the finds of ancient Jaffna and Tamil Nadu are indicators of a continuous cultural exchange between the two regions from classical antiquity.[21] These structures built over burials demonstrate the integration of Buddhism with Megalithism, a hallmark of Tamil Buddhism. Outside Andhra Pradesh in India, Kanterodai is perhaps the only site where such burials are seen.

Education

Kandarodai has a number of education institutions notably Kantharodai Tamil Kandaiya Vidyasalai and Skandavarodaya College.

Gallery

Buddhist Archeological excavations at Kandarodai in Jaffna, ruins dated to the 9th century AD.

Buddhist Archeological excavations at Kandarodai in Jaffna, ruins dated to the 9th century AD. Part of farm land near Kandarodai in Jaffna peninsula.

Part of farm land near Kandarodai in Jaffna peninsula.- One of the Tamil plaque.

See also

- Nallur (Jaffna)

- Vallipuram

- Naguleswaram temple

- Nainativu

- Kudiramalai

Notes

- In an excavation of Kandarodai by a team of archaeologists from the Pennsylvania University in the USA in 1970 a potsherd having lithic inscription of a few letters in Brahmi script was discovered and tagged as KTD14.....The potsherd being the only oldest inscribed artifact discovered in the Jaffna is of utmost importance. It is also the only artifact with genuine Brahmi scripting and symbols discovered in the Jaffna District....In 1973 Prof Indrapala leaves the following observations...."Its language bears the same language used in the pre-Christian cave inscriptions. It is in Sinhala Prakrit. Datahapata means Dattaha's begging bowl...."

References

- Archaeological Department Centenary (1890-1990): History of the Department of Archaeology. Commissioner of Archaeology. 1990. p. 175.

- Wijesekera, Nandadeva (1990). Archaeological Department Centenary (1890-1990): History of the Department of Archaeology. Commissioner of Archaeology. p. 175.

- Asia, International Association of Historians of (1988). Eleventh IAHA Conference: International Association of Historians of Asia, Colombo, 1-5 August 1988. The Association. p. 46.

- Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. pp. 89, 90.

Researches on the probable capital of the Naga line of kings of Jaffna, favour the present village of Kantharodai as the site of the Naga capital of Jaffna (page 89).

- Asia, International Association of Historians of (1988). Eleventh IAHA Conference: International Association of Historians of Asia, Colombo, 1-5 August 1988. The Association. p. 45.

- Wijebandara, I.D.M. (2014). Yapanaye Aithihasika Urumaya (Historic Legacy of Jaffna) (in Sinhala). p. 93. ISBN 978-955-9159-95-7.

Sinhala: කදුරුගොඩ යන නාම සම්භවය ගැන සදහන් වන තැන කඳුරුගොඩ යන්න පැරණි සිංහල වචනයක් වන කඳවුරුගොඩ යන්නෙන් බිඳී අැත. (එය හමුදාමය කටයුතු සඳහා භාවිත භූමියකි.) මෙම කඳවුරුගොඩ කඳුරුගොඩ වූ අතර එහි ද්රවිඩ රූපය කන්දරෝඩෙයි විය.

English: Where the etymology of Kadurugoda is mentioned, Kadurugoda has been broken from old Sinhalese word Kandavurugoda (It is a land used for military purposes). This Kandavurugoda became Kadurugoda and it's Tamilised (or Dravida) form was Kandarodai) - Rasanayagam, C.; Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar C. (1993). Ancient Jaffna: Being a Research Into the History of Jaffna from Very Early Times to the Portuguese Period. Asian Educational Services. p. 59. ISBN 9788120602106.

- Paul E. Pieris (1917). Nagadeepa and Buddhist remains in Jaffan. Journal of the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic society. p. 13.

- Godakumbura, C. (1968). "Kantarodai". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society: 67–85.

- (Begley,V. 1973)

- Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (7 September 1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780521376952.

- Dias, M.; Koralage, S.B.; Asanga, K. (2016). The archaeological heritage of Jaffna peninsula. Colombo: Department of Archaeology (Sri Lanka). pp. 222, 223. ISBN 978-955-9159-99-5.

- Dayalan, D. (2003). Kalpavr̥ks̥a: Essays on Art, Architecture and Archaeology. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 161. ISBN 9788180900037.

- Intirapālā, Kārttikēcu (2005). The evolution of an ethnic identity: the Tamils in Sri Lanka c. 300 BCE to c. 1200 CE. M.V. Publications for the South Asian Studies Centre, Sydney. p. 63. ISBN 9780646425467.

- International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2009. p. 62.

- S. Krishnarajah (2004). University of Jaffna

- Rásanáyagam, C.; Gunasekara, A. Mendis (1922). "THE TAMIL KINGDOM OF JAFFNA AND THE EARLY GREEK WRITERS". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 29 (75): 46. JSTOR 43483754.

- Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 183.

- Pillay, Kolappa Pillay Kanakasabhapathi (1963). South India and Ceylon. University of Madras. p. 117.

- Schalk, Peter; Veluppillai, A.; Nākacāmi, Irāmaccantiran̲ (2002). Buddhism among Tamils in pre-colonial Tamilakam and Īlam: Prologue. The Pre-Pallava and the Pallava period. Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 94. ISBN 9789155453572.

- Man and environment (2002). Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. Volume 27, Issue 2. pp. 27

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kandarodai. |