K. Kunhikannan

K. Kunhikannan (or K. Kunhi Kannan in journals) (15 October 1884 – 4 August 1931[1]) was a pioneer agricultural entomologist and the first Indian to serve as an entomologist in the state of Mysore. Aside from entomology related publications, he wrote two books The West (1927) and A Civilisation at Bay (1931, posthumously published). He was a friend and admirer of the humanist Brajendra Nath Seal and the British writer Lionel Curtis who sought a single united world government. As an agricultural entomologist, he identified several low-cost techniques to pest management and was a pioneer of classical biological control approaches in India.

Life and career

Kunhikannan was born in Kannur in the Kunnathedath family (which he used only by the initial "K."). He graduated from the University of Madras and was appointed as an assistant to Leslie C. Coleman, the first government entomologist in the State of Mysore (Coleman was the first entomologist to be appointed in any province or state of India[2]) on 19 November 1908 at a salary of Rs 150 per month. He was sent to study at Stanford University and his Ph.D. dissertation was on The function of the prothoracic plate in mylabrid (Bruchid) larvae: (a study in adaptation) (1923). He visited Hawaii several times between 1920 and 1921 attending meetings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society[3] and he also served as an Indian delegate (along with Swami Abhedananda) at the First Pan-Pacific Educational Conference from August 11–24, 1921.[4] From 1914, with Coleman as director of agriculture, most entomology work was carried out by Kunhikannan.[5] In 1923 he was made entomologist to the State of Mysore. Through his career, he took a special interest in cost-effective approaches to managing insect damage to crops and stored products.[6][7] Kunhikannan was appointed to the board of Mysore University on 23 July 1927, the Vice Chancellor at the time being Sir Brajendra Nath Seal.[8] When a proposal was made to offer marine biology at the Mysore University, Kunhikannan opposed it on the grounds that students needed to be able to relate to the environment immediately around them and not be far away from it.[6]

An asthmatic from an early age, he was physically not very active. As a young man he held radical views about which he was outspoken while his father, well read in Sanskrit lore, advised that when you consider all aspects, you will feel convinced that your views are hasty. After his stay and travels to the United States and through Europe, he wrote about his views in a book called The West (1927), with admiration for some aspects and strong criticism of others. He saw first-hand, the lynching of blacks in the United States which disturbed him greatly and he wrote about the dangers of media control (by William Randolph Hearst in this case) and the fierce individualism that was encouraged by the West. An Indian reviewer considered it one of the fair reviews of the West at a time when eastern criticism had become fashionable.[9] After receiving a lot of interest in his 1927 book he considered several other books, one on India and still others on education and other subjects. His book on India which was to be his comments on the Round Table Conferences to discuss the future of India was published posthumously in a book titled A Civilisation at Bay (1931). The book supported various Indian traditions with a chapter on the merits of the joint family, four chapters covering caste that include theories for its origin and rationalizations for its existence. In a talk delivered at Stanford, he explored the history and development of philosophy and science in India.[10]

C.F. Andrews, friend and follower of Gandhi, quoted Kunhikannan's The West extensively in his book The True India (1939) stating that One of the reasons I have chosen to quote so largely from Dr Kunhikannan in this chapter is because the note of bitterness is absent from his writing. His desire to be fair to the Western system is transparent.[11] D. V. Gundappa recounted that Kunhikannan was a member of a literature study group called Bangalore Study Club that ran in K.S. Krishna Iyer’s Irish Press near Siddikatte. Members included Anantapadmanabha Iyer, brother of Balasundaram Iyer a Municipal Councillor. Kunhikannan signed with his initials as "K. K. K." which was expanded jocularly as ಕ್ರಿಮಿಕೀಟಕಾಲಾಂತಕ (Krimi-Kīṭa-Kālāntaka = "Killer of germs and insects").[12]

Contributions to applied entomology

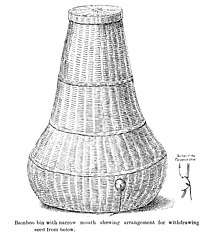

In his early years, Kunhikannan took an interest in natural history and made several casual observations and notes, in 1907[13] he observed that bats (Scotophilus kuhli) that roosted in hollows of coconut palms were infested by bedbugs that he identified as Cimex rotundatus.[14] In 1912 he noted that Papilo polytes was trimorphic in Bangalore.[15] As an agricultural entomologist, he was keenly sensitive to traditional practices and the economic situation of farmers. Keeping with the idea of cost efficiency in control measures against insects, he considered the use of a mesh below manure heaps that allowed coconut beetles (Oryctes) to burrow down as larvae but blocked the emergence of hard-bodied adults.[16] Kunhikannan was also firm in the belief that ancient practices often had their roots in well-founded facts. He examined traditional storage technique which involved the use of bamboo bins and straw. He examined the effect of mercury vapour[17] on the control of pulse beetles in storage, a system used by Mysore farmers for centuries, and found them to inhibit the development of eggs when used in small containers.[18][19][20] He also found that some farmers used of a layer of castor oil on the top of seeds placed in a bamboo bin along with a few drops of mercury. He found that the castor oil layer did help in keeping down emergence of pulse beetles. He also observed the practice of storing pulses under a layer of ragi. He found that pulse beetles emerge to the surface and do not return below, reducing the damage to pulses. He then found that a layer of sand at least half an inch thick at the top of grains helped in effectively controlling damage at little cost.[21] A similar approach was independently arrived by T.B. Fletcher based on studies in Pusa.[22] Kunhikannan also investigated traditionally used fish-poison plants and identified an alcoholic extract of Mundulea sericea as a treatment of wood against termites.[23][24] He noted the effectiveness of using a layer of kerosene in rice fields to control Nymphula depunctalis.[3][25]

Kunhikannan expressed his views on the content for agricultural education at a conference in 1923. He believed that farmers who knew the practices of farming from their traditions ought to be provided short one-year courses to supplement their knowledge rather than be provided with "alien ideas".[26] He examined the effect of the Lantana seed fly (Agromyza (Ophiomyia) lantanae) in Hawaii and was of the opinion that it had little effect in destroying the seeds. The fly was however released in Bangalore and although populations established widely, there was no reduction in Lantana.[27] Later studies showed that seed viability is reduced, but not enough to be an effective control.[28] Along with Coleman, he was involved in the introduction of cochineal insects from Ceylon to control Opuntia.[29][30][31] He introduced techniques for mass-rearing Trichogramma parasites on Corcyra for control of lepidopteran sugarcane pests.[32] In 1926 Kunhikannan examined the growth of robber-flies Hyperechia xylocopiformis and was able to show that they grew up inside the cells of Xylocopa bees, feeding on the bee larvae.[33]

Kunhikannan recorded a variation in Coccus viridis which initially appeared to have a seven segmented antenna as in Sri Lanka but he claimed that later populations tended to have a reduction over time in segments to five, four and finally most had three segmented antenna. He called the new South Indian form Coccus colemani "as a mark of gratitude for the valuable scientific training I have received" from Coleman. It is sometimes treated a subspecies of C. viridis. E.E. Green did not believe that this was a mutation as claimed by Kunhikannan.[34]

Kunhikannan was a promoter of Mesquite (Algaroba or Prosopis humilis) as a plant for the arid-zone and introduced it to the Hebbal farm.[35][36] In the last years of his life, Kunhikannan was studying the spread of the coffee borer beetle in Mysore, then known as Stephanoderes hampei.[37] Kunhikannan claimed that the beetle was first detected in Mysore in June 1930.[38]

Publications

Apart from the two books and brochures published as part of the Department of Agriculture, Kunhikannan also contributed reports and short papers, a partial list of which includes:

- A serious Pest of Cardamoms (Planters' Chronicle, XIX. No. 14, pp. 824–836, December 1924—from Journal Mysore Agric. Union; also in Mysore Agricultural Calendar 1925, pp. 32–36).

- The Coffee Borer. (Mysore Agric. Dept. Calendar 1925 pp. 5–8.) [Xylotrechus quadripes.]

- Report of the Entomologist, (Ann. Rept. Agric. Dept. Mysore, pt. II, pp. 10–12, 1925.)

- The Lime Tree Borer (Chelidonium cinctum), (Mysore Agricultural Calendar 1924: pp. 16–18)

- The Coffee Borer (The Planters' Chronicle, XX, pp. 922–924, Dec. 1925.)

- The Jola Ear-head Fly. (Journ. Mysore Agric. and Exper. Union, VII, p. 85, 1925.) [Atherigona soccata]

Kunhikannan was a subscriber to the newsletter of the Servants of India Society run from Poona. To this periodical, he contributed reviews of books on a range of topics including:

- A Die-hard on India. Review of Swaraj: The Problem of India by J.E. Ellam. (1931) Servant of India 14(3):34.

- Evolution of Civilization. Review of Civilization in Transition (1789-1870) by H.C. Thomas and W.A. Hamm. (1930) Servant of India 13(19):226.

- The New Faith [dealing with humanism]. Review of A Preface to Morals by Walter Lippman. (1930) Servant of India 13(18):212-213.

Death

Kunhikannan died suddenly from a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of 47. He was married to Koussalia who published his 1931 book posthumously through G.A. Natesan publishers. Coleman in a tribute to Kunhikannan stated that Kunhikannan's name "will find enduring association with Entomological investigations in this State, more especially with reference to the devising of methods of insect control adapted to our conditions.... Dr Kunhikannan displayed a real genius and his is a shining example for the Entomologist of the future".[6] Kunhikannan was succeeded in his position as entomologist to the state of Mysore by T.V. Subramaniam, brother of T. V. Ramakrishna Ayyar.[39] Gynaikothrips kannani a thrips species collected on Eugenia from Bangalore was named after him by the Californian entomologist Dudley Moulton in 1929.[40][41]

References

- Proceedings of the Thirty-eighth annual general meeting of the United Planters' Association of Southern India. 1931. p. 28.

- Husain, M. Afzal (1939). "Entomology in India: Past, Present and Future.". Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Indian Science Congress, Calcutta, 1938. pp. 201–246.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1922). "Condition of entomological work in India". Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 5: 71–73.

- Stavig, Gopal (2010). Western Admirers of Ramakrishna and His Disciples. Advaita Ashrama. p. 773.

- Report on the progress of agriculture in Mysore (2 ed.). Department of Agriculture, Mysore State. 1939. pp. 42–43.

- Kunhikannan, K. (1931). "A Brief Memoir of the Author". A Civilisation at Bay. India-Past, Present and Future. Madras: G.A. Natesan & Co.

- Ayyar, T.V. Ramakrishna (1931). "Obituary". The Madras Agricultural Journal. 19: 484.

- Annual Report of the University of Mysore 1926-27. 1927. p. 69.

- Ruthnaswamy, M. (1928). "Review. The West. by K. Kunhi Kannan". Servant of India. 11 (46): 618.

- "Scientific work in India [Lecture delivered at the Leland Stanford University, California, USA]". The Mysore University Magazine (July): 125–132. 1923.

- Andrew, C.F. (1939). The True India. A Plea for Understanding. London: George Allen & Unwin. pp. 84–88.

- Gundappa, D.V. (1950). ಜ್ಞಾಪಕಚಿತ್ರಶಾಲೆ [Jnapakachitrashaale (Volume 1)] – Sahiti Sajjana Sarvajanikaru (in Kannada).

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1924). "Protective colouration in wild animals". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 29: 1043.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1912). "The Bed Bug (Cimex rotandatus) on the Common Yellow Bat (Scotophilus kuhli.)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 21: 1342.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1912). "Papilio polytes in Bangalore". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 21: 699.

- Kunhikannan, K. (1910). "An interesting principle in economic entomology and some useful applications". Bulletin of Entomological Research: 404.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1920). "Mercury as an insecticide". Report of the Proceedings of the Third Entomological Meeting. Volume 2. Calcutta: Government Press. pp. 761–762.

- Rao, Y. Ramachandra (1923). "A biochemical discovery of the Ancient Babylonians". Journal of the Madras Agricultural Students' Union. 11 (5): 177–178.

- Larson, A.O. (1922). "Metallic mercury as an insecticide". Jour. Econ. Ent. 15 (6): 391–395. doi:10.1093/jee/15.6.391.

- Gough, H. C. (1938). "Toxicity of Mercury Vapour to Insects". Nature. 141 (3577): 922–923. doi:10.1038/141922c0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1919). Entomological Series. Bulletin No. 6. Pulse beetles (Store Forms). Department of Agriculture, Mysore State. pp. 22–24.

- Fletcher, T. Bainbrigge 712-761. "Stored grain pests". Report of the Proceedings of the Third Entomological Meeting Held at Pusa on the 3rd to 15th February 1919.

- Plants of possible insecticidal value : a review of the literature up to 1941. USDA. 1945. p. 93.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1914). "On some timbers which resist the attack of termites". Indian Forester. 40 (1): 23–41.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1922). "Conditions of Entomological Work in India" (PDF). Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomological Society. 5 (1): 71–73.

- "Editorial Notes. The Agricultural Conference [15 July 1923]". Journal of the Madras Agricultural Students' Union. 11 (7): 345–352. 1923.

- Subramaniam, T.V. (1936). "The Lantana seedfly in India, Agromyza (Ophiomyia) lantanae Froggatt". Indian Journal of Agricultural Science. 4: 468–470.

- Vivian-Smith, Gabrielle; Gosper, Carl R.; Wilson, Anita; Hoad, Kate (2006). "Lantana camara and the fruit- and seed-damaging fly, Ophiomyia lantanae (Agromyzidae): Seed predator, recruitment promoter or dispersal disrupter?". Biological Control. 36 (2): 247–257. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.07.017.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1928). "The control of cactus in Mysore". Mysore Agricultural Calendar: 16–71.

- Kunhikannan, K. (1915). "An aggressive mimic of the red tree ant". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 24: 373–374.

- Kunhikannan, K. (1930). "Control of Cactus in Mysore by means of Insects". Journal of the Mysore Agricultural and Experimental Union. 11 (2): 95–98.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1931). "The mass Rearing of the Egg Parasites of the Sugarcane Moth Borer in Mysore (Preliminary Experiments)". J. Mysore Agric. Expt. Union. 22 (2): 1–5.

- Poulton, E. B. (1926). "Proof by Dr. Kunhi Kannan that the larva of Hyperechia xylocopiformis, Walk., preys upon the larva of Xylocopa tenuiscapa, Westw. S. India". Proceedings of the Entomological Society of London: 1–2.

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1918). "An Instance of Mutation: Coccus viridis, Green, a mutant from Pulvinaria psidii, Maskell". Trans. Ent. Soc. London. 66: 130–148. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1918.tb02591.x.

- Kunhikannan, K. (1923). "A useful plant for India". The Agricultural Journal of India. 18 (1): 144–147.

- Report of the Progress of Agriculture in Mysore. 1939. p. 100.

- Letter from the Director of Agriculture in Mysore No RoC 2621, Sc. 584/29-30. 1930-05-23. pp. 12–17.

- Kunhi Kannan, K. (1930). "The Coffee Berry Borer (Stephanoderes hampei). A preliminary Account". Bull. Mysore Coffee Expt. Sta. 2.

- ChannaBasavanna, G.P. (1971). "Agricultural Entomology in Mysore: 1946-71". Agricultural College, Hebbal 1946-1971. Silver Jubilee Souvenir. Bangalore: University of Agricultural Sciences. pp. 58–70.

- Ayyar, T.V. Ramakrishna; Margabandhu, V. "Notes on Indian Thysanoptera with brief descriptions of new species". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 34: 1029–1040.

- Moulton, Dudley (1929). "A new species of Gynaikothrips from Bangalore, India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33: 667.

External links

- The West (1927)

- A Civilisation at Bay (1931)

- Kannan, K. Kunhi (1919). Entomological Series. Bulletin No. 6. Pulse beetles (Store Forms). Department of Agriculture, Mysore State.

- Coleman, Leslie C.; Kannan, K. Kunhi (1918). Entomological Series. Bulletin No. 4. Some scale insect pests of coffee in South India. Department of Agriculture, Mysore State.

- Coleman, Leslie C.; Kunhikannan, K. (1918). Entomological Series. Bulletin No. 5. Ground beetles attacking crops in Mysore. Department of Agriculture, Mysore State.

- Coleman, Leslie C. (assisted by K. Kunhi Kannan) (1911). Entomological Series. Bulletin No. 1. The Rice Grasshopper (Hieroglyphus banian, Fabr.). Department of Agriculture, Mysore State.