Kőnig's lemma

Kőnig's lemma or Kőnig's infinity lemma is a theorem in graph theory due to the Hungarian mathematician Dénes Kőnig who published it in 1927.[1] It gives a sufficient condition for an infinite graph to have an infinitely long path. The computability aspects of this theorem have been thoroughly investigated by researchers in mathematical logic, especially in computability theory. This theorem also has important roles in constructive mathematics and proof theory.

Statement of the lemma

Let G be a connected, locally finite, infinite graph (this means: any two vertices can be connected by a path, the graph has infinitely many vertices, and each vertex is adjacent to only finitely many other vertices). Then G contains a ray: a simple path (a path with no repeated vertices) that starts at one vertex and continues from it through infinitely many vertices.

A common special case of this is that every infinite tree contains either a vertex of infinite degree or an infinite simple path.

Proof

Start with any vertex v1. Every one of the infinitely many vertices of G can be reached from v1 with a simple path, and each such path must start with one of the finitely many vertices adjacent to v1. There must be one of those adjacent vertices through which infinitely many vertices can be reached without going through v1. If there were not, then the entire graph would be the union of finitely many finite sets, and thus finite, contradicting the assumption that the graph is infinite. We may thus pick one of these vertices and call it v2.

Now infinitely many vertices of G can be reached from v2 with a simple path which does not include the vertex v1. Each such path must start with one of the finitely many vertices adjacent to v2. So an argument similar to the one above shows that there must be one of those adjacent vertices through which infinitely many vertices can be reached; pick one and call it v3.

Continuing in this fashion, an infinite simple path can be constructed using mathematical induction and a weak version of the axiom of dependent choice. At each step, the induction hypothesis states that there are infinitely many nodes reachable by a simple path from a particular node vi that does not go through one of a finite set of vertices. The induction argument is that one of the vertices adjacent to vi satisfies the induction hypothesis, even when vi is added to the finite set.

The result of this induction argument is that for all n it is possible to choose a vertex vn as the construction describes. The set of vertices chosen in the construction is then a chain in the graph, because each one was chosen to be adjacent to the previous one, and the construction guarantees that the same vertex is never chosen twice.

Computability aspects

The computability aspects of Kőnig's lemma have been thoroughly investigated. The form of Kőnig's lemma most convenient for this purpose is the one which states that any infinite finitely branching subtree of has an infinite path. Here denotes the set of natural numbers (thought of as an ordinal number) and the tree whose nodes are all finite sequences of natural numbers, where the parent of a node is obtained by removing the last element from a sequence. Each finite sequence can be identified with a partial function from to itself, and each infinite path can be identified with a total function. This allows for an analysis using the techniques of computability theory.

A subtree of in which each sequence has only finitely many immediate extensions (that is, the tree has finite degree when viewed as a graph) is called finitely branching. Not every infinite subtree of has an infinite path, but Kőnig's lemma shows that any finitely branching subtree must have such a path.

For any subtree T of the notation Ext(T) denotes the set of nodes of T through which there is an infinite path. Even when T is computable the set Ext(T) may not be computable. Every subtree T of that has a path has a path computable from Ext(T).

It is known that there are non-finitely branching computable subtrees of that have no arithmetical path, and indeed no hyperarithmetical path.[2] However, every computable subtree of with a path must have a path computable from Kleene's O, the canonical complete set. This is because the set Ext(T) is always (see analytical hierarchy) when T is computable.

A finer analysis has been conducted for computably bounded trees. A subtree of is called computably bounded or recursively bounded if there is a computable function f from to such that for every sequence in the tree and every n, the nth element of the sequence is at most f(n). Thus f gives a bound for how “wide” the tree is. The following basis theorems apply to infinite, computably bounded, computable subtrees of .

- Any such tree has a path computable from , the canonical Turing complete set that can decide the halting problem.

- Any such tree has a path that is low. This is known as the low basis theorem.

- Any such tree has a path that is hyperimmune free. This means that any function computable from the path is dominated by a computable function.

- For any noncomputable subset X of the tree has a path that does not compute X.

A weak form of Kőnig's lemma which states that every infinite binary tree has an infinite branch is used to define the subsystem WKL0 of second-order arithmetic. This subsystem has an important role in reverse mathematics. Here a binary tree is one in which every term of every sequence in the tree is 0 or 1, which is to say the tree is computably bounded via the constant function 2. The full form of Kőnig's lemma is not provable in WKL0, but is equivalent to the stronger subsystem ACA0.

Relationship to constructive mathematics and compactness

The proof given above is not generally considered to be constructive, because at each step it uses a proof by contradiction to establish that there exists an adjacent vertex from which infinitely many other vertices can be reached, and because of the reliance on a weak form of the axiom of choice. Facts about the computational aspects of the lemma suggest that no proof can be given that would be considered constructive by the main schools of constructive mathematics.

The fan theorem of L. E. J. Brouwer (1927) is, from a classical point of view, the contrapositive of a form of Kőnig's lemma. A subset S of is called a bar if any function from to the set has some initial segment in S. A bar is detachable if every sequence is either in the bar or not in the bar (this assumption is required because the theorem is ordinarily considered in situations where the law of the excluded middle is not assumed). A bar is uniform if there is some number N so that any function from to has an initial segment in the bar of length no more than . Brouwer's fan theorem says that any detachable bar is uniform.

This can be proven in a classical setting by considering the bar as an open covering of the compact topological space . Each sequence in the bar represents a basic open set of this space, and these basic open sets cover the space by assumption. By compactness, this cover has a finite subcover. The N of the fan theorem can be taken to be the length of the longest sequence whose basic open set is in the finite subcover. This topological proof can be used in classical mathematics to show that the following form of Kőnig's lemma holds: for any natural number k, any infinite subtree of the tree has an infinite path.

Relationship with the axiom of choice

Kőnig's lemma may be considered to be a choice principle; the first proof above illustrates the relationship between the lemma and the axiom of dependent choice. At each step of the induction, a vertex with a particular property must be selected. Although it is proved that at least one appropriate vertex exists, if there is more than one suitable vertex there may be no canonical choice. In fact, the full strength of the axiom of dependent choice is not needed; as described below, the axiom of countable choice suffices.

If the graph is countable, the vertices are well-ordered and one can canonically choose the smallest suitable vertex. In this case, Kőnig's lemma is provable in second-order arithmetic with arithmetical comprehension, and, a fortiori, in ZF set theory (without choice).

Kőnig's lemma is essentially the restriction of the axiom of dependent choice to entire relations R such that for each x there are only finitely many z such that xRz. Although the axiom of choice is, in general, stronger than the principle of dependent choice, this restriction of dependent choice is equivalent to a restriction of the axiom of choice. In particular, when the branching at each node is done on a finite subset of an arbitrary set not assumed to be countable, the form of Kőnig's lemma that says "Every infinite finitely branching tree has an infinite path" is equivalent to the principle that every countable set of finite sets has a choice function, that is to say, the axiom of countable choice for finite sets.[3][4] This form of the axiom of choice (and hence of Kőnig's lemma) is not provable in ZF set theory.

Generalization

In the category of sets, the inverse limit of any inverse system of non-empty finite sets is non-empty. This may be seen as a generalization of Kőnig's lemma and can be proved with Tychonoff's theorem, viewing the finite sets as compact discrete spaces, and then using the finite intersection property characterization of compactness.

See also

- Aronszajn tree, for the possible existence of counterexamples when generalizing the lemma to higher cardinalities.

- PA degree

Notes

- Kőnig (1927) as explained in Franchella (1997)

- Rogers (1967), p. 418ff.

- Truss (1976), p. 273; compare Lévy (1979), Exercise IX.2.18.

- Howard, Paul; Rubin, Jean (1998). Consequences of the Axiom of Choice. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. 59. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society.

References

- Brouwer, L. E. J. (1927), On the Domains of Definition of Functions. published in van Heijenoort, Jean, ed. (1967), From Frege to Gödel.

- Cenzer, Douglas (1999), " classes in computability theory", Handbook of Computability Theory, Elsevier, pp. 37–85, doi:10.1016/S0049-237X(99)80018-4, ISBN 0-444-89882-4, MR 1720779.

- Kőnig, D. (1926), "Sur les correspondances multivoques des ensembles" (PDF), Fundamenta Mathematicae (in French) (8): 114–134.

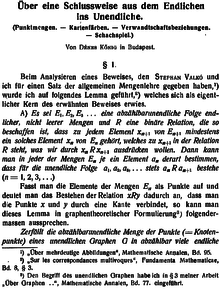

- Kőnig, D. (1927), "Über eine Schlussweise aus dem Endlichen ins Unendliche", Acta Sci. Math. (Szeged) (in German) (3(2-3)): 121–130, archived from the original on 2014-12-23, retrieved 2014-12-23.

- Franchella, Miriam (1997), "On the origins of Dénes König's infinity lemma", Archive for History of Exact Sciences (51(1)3:2-3): 3–27, doi:10.1007/BF00376449.

- Howard, Paul; Rubin, Jean (1998), Consequences of the Axiom of Choice, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, 59, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society.

- Kőnig, D. (1936), Theorie der Endlichen und Unendlichen Graphen: Kombinatorische Topologie der Streckenkomplexe (in German), Leipzig: Akad. Verlag.

- Lévy, Azriel (1979), Basic Set Theory, Springer, ISBN 3-540-08417-7, MR 0533962. Reprint Dover 2002, ISBN 0-486-42079-5.

- Rogers, Hartley, Jr. (1967), Theory of Recursive Functions and Effective Computability, McGraw-Hill, MR 0224462.

- Simpson, Stephen G. (1999), Subsystems of Second Order Arithmetic, Perspectives in Mathematical Logic, Springer, ISBN 3-540-64882-8, MR 1723993.

- Soare, Robert I. (1987), Recursively Enumerable Sets and Degrees: A study of computable functions and computably generated sets, Perspectives in Mathematical Logic, Springer, ISBN 3-540-15299-7, MR 0882921.

- Truss, J. (1976), "Some cases of König's lemma", in Marek, V. Wiktor; Srebrny, Marian; Zarach, Andrzej (eds.), Set theory and hierarchy theory: a memorial tribute to Andrzej Mostowski, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 537, Springer, pp. 273–284, doi:10.1007/BFb0096907, MR 0429557.

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Constructive Mathematics

- The Mizar project has completely formalized and automatically checked the proof of a version of König's lemma in the file TREES_2.