Jupiter Hammon

Jupiter Hammon (1711-ca. 1806) is known as a founder of African-American literature, as his poem published in 1761 in New York was the first by an African American in North America. He published both poetry and prose after that. In addition, he was a preacher and a commercial clerk on Long Island, New York.

Born into slavery at the Lloyd Manor on Long Island,[1][2] Hammon learned to read and write. In 1761, at the age of nearly 50, Hammon published his first poem, "An Evening Thought. [sic] Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries." He was the first African-American poet published in North America.[1] Also a well-known and well-respected preacher and clerk-bookkeeper, he gained wide circulation of his poems about slavery. As a devoted Christian evangelist, Hammon used his biblical foundation to criticize the institution of slavery.[3]

Early life and education

Details about Jupiter Hammon's life are buried in the unaddressed history of slavery in the Northern U.S states.[3] The facts of Hammon's personal life are limited or non existent. Opium and Rose, slaves purchased by Henry Lloyd, are believed to have been the parents of Jupiter Hammon.[3] They are the first set of male and female slaves on record in the Lloyd Papers to serve the Lloyd family continually after their purchase.[3] Born into slavery at the Lloyd Manor (at what is now Lloyd Harbor, New York), Hammon served the Lloyd family his entire life, working under four generations of the family masters.[3]

The Lloyds allowed Hammon to receive a rudimentary education through the Anglican Church's Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts system, likely in exchange for his cooperative attitude.[4][3] Hammon's ability to read and write aided his slave masters in their commercial businesses; these supported institutionalized slavery.[3] Hammon's goal was to take advantage of the literary skills by exhibiting a level of intellectual awareness through literature.[3] In doing so, he created literature layered in metaphors and symbols, giving him a safe means to express his feelings of slavery.[3]

Literary works

"An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries" was Jupiter Hammon's first published poem.[5] Composed on December 25th 1760, it appeared as a broadside in 1761.[5] The printing and publishing of this poem established Jupiter Hammon as the first black published author.[6]

Eighteen years passed before his second work appeared in print, "An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley."[6] Hammon wrote the poem during the Revolutionary War, while Henry Lloyd had temporarily moved his household and slaves from Long Island to Hartford, Connecticut, to evade British forces.[7] Phillis Wheatley, then enslaved in Massachusetts, published her first book of poetry in 1773 in London. She is recognized as the first published black female author.[8] Hammon never met Wheatley, but was a great admirer.[7] His dedication poem to her contained twenty-one rhyming quatrains, each accompanied by a related Bible verse.[9] Hammon believed his poem would encourage Wheatley along her Christian journey.[7]

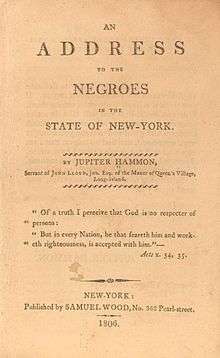

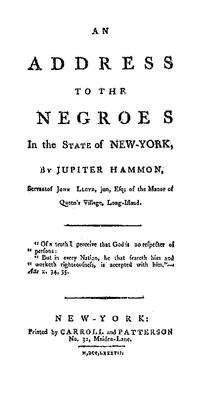

In 1778 Hammon published "The Kind Master and Dutiful Servant," a poetical dialogue, followed by "A Poem for Children with Thoughts on Death" in 1782.[7] These works set the tone for Hammon's "An Address to Negros in the State of New York."[6] At the inaugural meeting of the African Society in New York City on September 24, 1786, Hammon delivered what became known as the Hammon "Address to Negroes of the State of New-York."[9] He was seventy-six years old and still enslaved.[10] In his address he told the crowd, "If we should ever get to Heaven, we shall find nobody to reproach us for being black, or for being slaves."[10] He also said that while he personally had no wish to be free, he did wish others, especially "the young negroes, were free."[10]

Hammon's speech draws heavily on Christian motifs and theology, encouraging Black people to maintain their high moral standards because "being slaves on Earth had already secured their place in heaven."[7] Scholars believe Hammon supported gradual abolition as a way to end slavery, believing that the immediate emancipation of all slaves would be difficult to achieve.[7] [11] New York Quakers who supported the abolition of slavery published Hammon's speech, and it was reprinted by several abolitionist groups, including the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.[11]

Hammon's full body of work consists of eight publications, four poems and four prose, all consisting of religious content. [6] "An Address to Negroes in the State of New York" was Hammon's last literary work and likely his most influential.[6] It is believed that Jupiter Hammon died within or before the year 1806.[7] Though his death was not recorded, it is believed that Hammon was buried separately from the Lloyds on the Lloyd family property in an unmarked grave.[7]

Recent findings

Two previously unknown poems by Hammon have been discovered in recent years. In 2013 University of Texas Arlington doctoral student Julie McCown discovered the first in the Manuscripts and Archives library at Yale University. The poem, dated 1786, is described by McCown as a 'shifting point' in Hammon's worldview surrounding slavery.[12] The second was found in 2015 by Claire Bellerjeau, a researcher investigating the Townsend family and their slaves who lived at Raynham Hall in nearby Oyster Bay.[13]

Works

- AN ADDRESS TO THE NEGROES In the STATE of NEW-YORK (1787) Online pdf edition

See also

- List of slaves

Further reading

- The Collected Works of Jupiter Hammon: Poems and Essays, ed. Cedrick May, University of Tennessee Press, 2017

References

- Berry, Faith (2001). From Bondage to Liberation. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. p. 50. ISBN 0-8264-1370-6.

- Rollins, Charlemae (1965). Famous American Negro Poets. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0396051294.

- O'Neal, Sondra (1993). Jupiter Hammon and The Biblical Beginnings of African American Literature. The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-2479-5.

- Berry, Faith (2001). From Bondage to Liberation. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. p. 50. ISBN 0-8264-1370-6.

- "An Evening Thought". University of Virginia Library. 1761. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- Berry, Faith (2001). From Bondage to Liberation. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. p. 50. ISBN 0-8264-1370-6.

- O'Neal, Sondra (1993). Jupiter Hammon and The Biblical Beginnings of African American Literature. The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-2479-5.

- Rollins, Charlemae (1965). Famous American Negro Poets. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0396051294.

- Jupiter, Hammon; Paul, Royster (editor) (22 September 1787). "An Address to the Negroes in the State of New-York (1787)". Electronic Texts in American Studies.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "An address to the negroes in the state of New-York". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- "Gale Schools – Black History Month – Literature – An Address to the Negroes". Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- "Forgotten Poem by First African-American Writer Found". NBC.

- "Researcher discovers new poem by Jupiter Hammon". Newsday. Retrieved 22 June 2020.