Jules Léotard

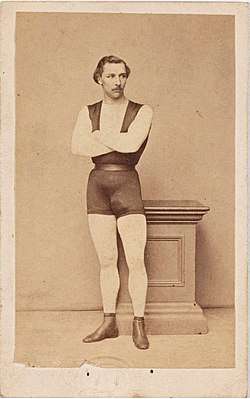

Jules Léotard (French: [leɔtaʁ]; August 1, 1838 – August 17, 1870) was a French acrobatic performer and aerialist who developed the art of trapeze. He also popularized the one-piece gym wear that now bears his name and inspired the 1867 song "The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze" sung by George Leybourne. He was also one of the cycling pioneers in France right before his untimely death.[1]

Jules Léotard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jules Léotard August 1, 1838 |

| Died | August 17, 1870 (aged 32) Toulouse, France |

| Known for | Trapeze Acrobatics |

Early life

Léotard was born in Toulouse, France, the son of a gymnastics instructor who ran a swimming pool in Toulouse. Léotard would practice his routines over the pool.[2] He went on to study law.

Career

After he passed his law exams, he seemed destined to join the legal profession.[3] But at 18 he began to experiment with trapeze bars, ropes and rings suspended over a swimming pool. Léotard later joined the Cirque Napoleon.[4]

On 12 November 1859, the first flying trapeze routine was performed by Jules Léotard on three trapeze bars at the Cirque Napoleon.[5]

The costume he invented was a one-piece knitted garment streamlined to suit the safety and agility concerns of trapeze performance. It also showed off his physique,[6] impressed women and inspired the song sung by George Leybourne.

In addition to having the leotard named after him, Jules Léotard was immortalised as the subject of the 1867 popular song, The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.

Death

According to notes from the Victoria and Albert Museum, Jules Léotard died in 1870 from an infectious disease (possibly smallpox).[7] They list his year of birth as 1838 despite there being good evidence he wasn't born until much later.

Notes

- "Palmares Jules Léotard at CyclingRanking.com". CyclingRanking.com.

- Lynch, Annette; Strauss, Mitchell D. (30 October 2014). Ethnic Dress in the United States: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7591-2150-8.

- McPherson, Douglas (1 April 2011). Circus Mania!. Peter Owen Publishers. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7206-1386-5.

- Cullen, Frank; Hackman, Florence; McNeilly, Donald (16 October 2006). Vaudeville old & new: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America. Psychology Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2.

- Steve Ward (27 May 2017). Sawdust Sisterhood: How Circus Empowered Women. Fonthill Media. p. 87. GGKEY:LKCCFDFW6CF.

- Marciano, John Bemelmans (3 November 2009). Anonyponymous: The Forgotten People Behind Everyday Words. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-60819-162-8.

- V&A museum biography

References

- Michael Diamond, Victorian Sensation, (Anthem Press, 2003) ISBN 1-84331-150-X. Pp. 262–264.

External links

- "Jules Leotard". Theatre and Performance. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2011-01-09. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jules Léotard. |