Jules De Bruycker

Jules De Bruycker (29 March 1870 – 5 September 1945) was a Belgian graphic artist, etcher, painter and draughtsman.[1] He is considered one of the foremost Belgian graphic artists after James Ensor and achieved a high level of technical virtuosity. He is best known for his scenes of his home town Ghent, architectural views of cathedrals, war prints and book illustrations.[2]

Life

Jules De Bruycker was born in Ghent. His family operated a small upholstery and wallpapering business. As De Bruycker displayed artistic talent from an early age, he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent when he was 10. When his father died four years later, he ceased to attend art classes and joined the family business. He continued to hone his artistic skills without formal training. After an interruption of 9 years, De Bruycker enrolled again at the Ghent Academy. His teachers included the painters Théo Canell, Louis Tijtgadt and Jean Delvin.[3]

In his early years as an artist (from 1902) De Bruycker took up lodgings at an abandoned Carmelite abbey in the district across from the Gravensteen called the Patershol.[4] This was at the time an impoverished area and it had attracted artists and bohemians who had moved there from about 1900. Many of the artists who would become part of the School of Latem such as Gustave van de Woestijne, George Minne and Valerius de Saedeleer converged on this area and George Minne even maintained a studio there for some time.[5]

Even as a member of this bohemian artist community in Ghent, De Bruycker continued to work in the family business during this period. While he made many watercolours and oil on canvas paintings in his early days, he developed an interest in printmaking after discovering in 1905 the etchings of the Ghent artist Albert Baertsoen in the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent.[3] Albert Baertsoen was known for his prints of city views of Ghent. These showed the city bathed in a dreamy atmosphere and a style which was close to symbolism.[6]

De Bruycker also made many drawings of scenes in the less privileged quarters of Ghent.[7] An example is the Around the Gravensteen in Ghent in which he depicts the area around the Gravensteen in Ghent in images reminiscent of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Hieronymous Bosch and his contemporary James Ensor.[4]

De Bruycker became an accomplished graphic artist and tutored Frans Masereel in graphic techniques before Masereel left Ghent for Paris and Brittany.[8] In 1905, De Bruycker was selected by the writer Franz Hellens as the illustrator of his first novel entitled En ville morte.[4]

With the outbreak of World War I, De Bruycker fled Belgium for England. Many other Belgian artists moved to England and Wales during the war. They included Emile Claus, Valerius de Saedeleer, Hippolyte Daeye, Albert Delstanche, Émile Fabry, Charles Mertens, George Minne, Isidore Opsomer, Gustave-Max Stevens, Gustave van de Woestijne and Albert Baertsoen. Among this community of Belgians in exile De Bruycker met Raphaëlle De Leyn, also a native of Ghent. The two got married. Prohibited from outdoor sketching due to the fear of spies, De Bruycker only produced a few views of London. Instead he worked on a series of large etchings which had as their theme the horrors of the war in Flanders. His work Death tolls over Flanders again was exhibited in Rotterdam in 1917 where it was favourably received. An art critic noted the work evoked the images of Bosch and Bruegel, but also the figure of Ulenspiegel from Charles De Coster's "The Legend of Thyl Ulenspiegel and Lamme Goedzak".

After returning to Belgium following the end of the war in 1919 De Bruycker soon started to receive official recognition for his artistic achievements. He was made a Knight in the Order of Leopold of Belgium in 1921 and had a successful exhibition of 154 works at the Galerie Giroux in Brussels in 1922. In the same year he had exhibitions at the Chicago Art Institute and other places in the United States (including Detroit and Muskegon).[2] He was offered a teaching post at the Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten (Higher Institute of Fine Arts) in Antwerp, a part of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Antwerp). He reluctantly accepted this position.[3] Frans van Immerseel was one of his pupils and studied etching with De Bruycker.[9] De Bruycker was named a correspondent of the Royal Academy of Belgium in 1923 and became a full member in 1925. In 1927 he received the national prize for fine art.

After his return to Ghent he took up residence in the Dominican Pand and in 1921 he made a series of drawings and etchings of the residents of his neighborhood. During the years 1922-1924 he made few prints but worked on 16 designs for woodcut illustrations for a new edition of Charles De Coster's Ulenspiegel.

In 1925 De Bruycker visited his friend Frans Masereel in Paris. Masereel encouraged him to work on architectural views which resulted in a series of prints of cathedrals in France and Belgium.[3] The St Nicholas Church of Ghent was one of his favourite subjects which he depicted in a series of large prints, all varying in slight detail.[3] Around the same time De Bruycker also started producing figure studies including self portraits, models and nudes. In 1934 he participated in the Venice Biennale.[3] He published a series of views of Ghent in 1932.

His health gradually started to dwindle, probably as a result of his exposure to acids during the etching process. He concentrated mainly on drawing. When the Germans occupied Belgium again in 1940, he produced a series of prints under the title 'Gens de chez nous – 1942' (People from here - 1942). He also worked on another album called 'Gens pas de chez nous' (People not from here). This latter series depicted the German occupiers. The six etchings in this series were only published after his death not long after the end of the war.[10] During the war German print lovers had visited De Bruycker and even asked him to produce a drawing for propaganda purposes which he refused categorically.[3]

Work

Jules De Bruycker practiced in various mediums including oil on canvas, watercolor, drawing and etching. He is now mainly remembered for his incisive drawings and prints. He achieved a high degree of technical virtuosity in his prints, which earned him the distinction of being called in his time 'the greatest Belgian etcher after Ensor'.[2]

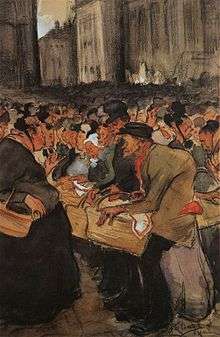

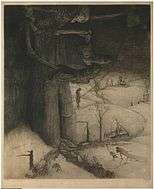

While in his early work De Bruycker adopted the gloomy, dreamy and nocturnal atmosphere he had seen in the print work of Albert Baertsoen, he did not follow the themes of Baertsoen. Baertsoen was an aristocrat who had a preference for city scenes of Ghent almost free of a human presence. De Bruycker, on the other hand, loved to include crowds of people and dramatic light effects in his graphic work.[6] De Bruycker's early etchings, dating from 1906 until the outbreak of the First World War, depict mainly four primary themes: the artist's haunts in and around the Patershol, the open-air flea markets with their rough, lowlife population, the cheap sections of the theater and some historic sites of old Ghent. He typically populated these scenes with a great number of people. His work provided an intimate view of the daily life of the economically deprived residents of his hometown. Some of his representations of the local population border on the caricatural but are never without empathy.[3]

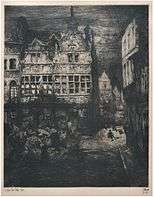

In his large plates from before World War I, such as House of Jan Palfyn, Ghent and Placing the Dragon on the Belfry of Ghent De Bruycker demonstrated the high level of virtuosity he had achieve as an etcher which allowed him to include rich detail and chiaroscuro effects. These works resemble the etchings of the Anglo-Welsh artist Frank Brangwyn, who assisted De Bruycker during the years of his exile in London. Although he produced some city views of London during the war, he mainly worked on large prints, which decried the violence and death that the war had brought to his country. The visual language of these prints drew from the Flemish traditions of Brueghel and Bosch as well as the story of Ulenspiegel. Flemish artists of De Bruycker’s generation had rediscovered the art of the Flemish primitives through the exhibition 'Les Primitifs Flamands' ('The Flemish Primitives') held in Bruges in 1902. Each artist had reacted to this rediscovery in a personal way.[3] Ensor's influence can also be seen in a few of De Bruycker's war prints. The preliminary studies for these etchings demonstrate De Bruycker’s talents as a draughtsman.[2] During his stay in London, De Bruycker met other artists such as Walter Sickert and got to know the work of James Whistler which influenced his work.

In the early 1920s he started to produce many prints of Cathedrals in Belgium and Northern France. His work from the mid 1920s included figure studies, including self-portraits, model drawings and nudes. Many of these works depict the studio environment or fanciful objects such as Buddhist statues, African masks etc. His nudes are particularly sensuous and even provocative and constituted an important new theme in his work.[3]

The work of Jules De Bruycker was influential on other artists of his generation. Gustave van de Woestijne was likely citing the incisive portraits by De Bruycker in his early portraits of around 1908.[11]

- Selected Artwork

Saint James Market in Ghent

Saint James Market in Ghent Antwerp Cathedral

Antwerp Cathedral Death tolls over Flanders again

Death tolls over Flanders again House of Jan Palfyn, Ghent

House of Jan Palfyn, Ghent Placing the Dragon on the Belfry of Ghent

Placing the Dragon on the Belfry of Ghent

References

- Jules De Bruycker at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Dirk Van Assche, The Etchings of Jules de Bruycker, in: The Low Countries. Jaargang 4. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, p. 310

- Stephen H. Goddard, Jules de Bruycker, 'An Eye on Flanders: The Graphic Art of Jules De Bruycker', Spencer Museum of Art, 1996

- Andre de Vries, 'Flanders: A Cultural History', Oxford University Press, 16 May 2007, p. 86-87

- Piet Boyens, Sint-Martens-Latem, Lannoo, 1992, p. 26 (in Dutch)

- Joost De Geest, '500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belge', Lannoo Uitgeverij, 2006, p. 109 (in French)

- Lebeer Louis , Jules de Bruycker - Oude verkoopster at Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen, 1971 (in Dutch)

- David A. Berona, Introduction, in: Frans Masereel, 'The Sun, The Idea & Story Without Words: Three Graphic Novels, Courier Corporation, 13 Nov 2012

- Willy Feliers, Frans van Immerseel: graficus, glazenier en stoetenbouwer, in: Tiecelijn. Jaargang 16. Vzw Tiecelijn-Reynaert / Marcel Ryssen, Sint-Niklaas 2003, p. 98 (in Dutch)

- Jules De Bruycker Biography at Stichting Jules De Bruycker (in Dutch)

- Piet Boyens, Sint-Martens-Latem, Lannoo, 1992, p. 268 (in Dutch)

External links

- Website of the stichting Jules De Bruycker (in Dutch)