Joseph Fox (dental surgeon)

Joseph Fox (7 November 1775 – 11 April 1816) was an English dental surgeon, known also as a philanthropist.[1] He was a pioneer writer and lecturer on dentistry.

Early life

He was the son of Joseph Fox, a dentist, and his wife, Mary Rogers, daughter of John Rogers, a Baptist minister of Southwark, and was born in Crooked Lane, in the City of London. A medical student at Guy's Hospital by 1794, he became dresser to the surgeon Henry Cline.[1] The lectures he gave on the teeth, from 1799, supported by Astley Cooper who was another of Cline's pupils, were the first to be delivered for a London medical institution.[2][3] According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, there was no British precedent, and possibly none worldwide.[1]

Fox built up a private dental practice in London. He belonged to the Particular Baptist church of John Rippon, in Carter Lane, London.[1]

Education and the Lancasterian system

In 1807 Fox was taken by Sir John Jackson, 1st Baronet to hear Joseph Lancaster lecture, in Dover. He then met Lancaster and his supporter William Corston in London, and heard the extent of Lancaster's financial difficulties with his education society.[4] With Corston and William Allen, Fox helped put the society, which became in time the British and Foreign School Society, on a sound basis.[1] The initial committee consisted of: Allen, Corston, Fox, Jackson, with Joseph Foster and Thomas Sturge.[5]

Lancaster himself chafed under the committee's tutelage, and became resentful. By 1812 he branched out with a boarding school at Tooting, without approval. Francis Place joined the committee that year, and a rupture became inevitable by 1814, with Lancaster resigning amid acrimony and alleged scandal.[6]

In 1814, Fox and Allen bought into the New Lanark project.[1] They were part of a consortium, including also Forster, put together by Robert Owen, to buy out the original New Lanark investors. The educational interests were relevant to Owen, who had been rebuffed by the Anglican Bell system, closed to dissenters.[7] Fox supported Allen in his successful effort to make Owen allow religious education and the Bible in New Lanark's schools.[8]

Associations

Fox was a member of the Askesian Society, and from 1798 was a supporter of Edward Jenner, making his house available for vaccinations. In 1800 he joined the Royal Institution. He corresponded with Josiah Wedgwood II, in particular on the topic of porcelain false teeth.[1]

From 1809 and its founding, to 1812, Fox was Secretary of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. He had Thomas Fry as colleague from 1810.[11]

Works

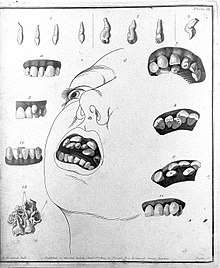

- The Natural History of the Human Teeth (1803)[1]

- The History and Treatment of the Diseases of the Teeth (1806). This and the Natural History were major early works of British dentistry, illustrated and giving details of procedures. There were British and American editions, and a French translation.[1] In the tradition of Thomas Berdmore, Fox wrote without extensive citation of authorities, meeting later objection from the French dentist Joseph Audibran.[12]

- A Comparative View of the Plans of Education, as Detailed in the Publications of Dr. Bell and Mr. Lancaster (1808)[13]

- A Vindication of Mr Lancaster's System of Education from the Aspersions of Professor Marsh, the Quarterly, British, and Anti-Jacobin Reviews, &c., &c. (1812)[14] Written by Fox under a pseudonym, Against Herbert Marsh and other Anglican clergy.[15] The letters making up the work were first published in The Statesman. There is a comparison of the Lancastrian system with that of Andrew Bell, a Scottish Episcopalian.[16] This and the previous book were contributions to a controversy, along the divide caused by nonconformism, in which Robert Southey involved himself, in the Quarterly Review.[17][18]

Family

Fox married in 1808 Ann Gibbs. They had a son and a daughter.[1]

Notes

- Cohen, R. A. "Fox, Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38625. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hillam, Christine (2003). Dental Practice in Europe at the End of the 18th Century. Rodopi. p. 32. ISBN 9789042012684. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- "King's Collections : Archive Catalogues : GUY'S HOSPITAL MEDICAL SCHOOL: Records". Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- American Journal of Education. Brownell. 1861. p. 363.

- Dunn, Henry (1848). Sketches. Part 1. Joseph Lancaster and his contemporaries. Part 2. William Allen, his life and labours. p. 70. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Bartle, G. F. "Lancaster, Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15963. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "New Lanark 1800 - 1825, Robert Owen Museum". Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bender, Thomas (1992-06-02). The Antislavery Debate: Capitalism and Abolitionism as a Problem in Historical Interpretation. University of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780520077799. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Ivimey, Joseph (1830). A History of the English Baptists. IV. London: Isaac Taylor Hinton. p. 383. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- The Baptist Magazine. 1816. p. 254.

- Gidney, W.T. The history of the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews. Рипол Классик. p. 38. ISBN 9781177644266. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bivins, R.; Pickstone, J. (2007-06-15). Medicine, Madness and Social History: Essays in Honour of Roy Porter. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 84. ISBN 9780230235359. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Fox, Joseph (1808). A Comparative View of the Plans of Education, as Detailed in the Publications of Dr. Bell and Mr. Lancaster. author. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- A Member of the Royal Institution [signed, Pythias]. (1812). A Vindication of Mr. Lancaster's system of education from the aspersions of Professor Marsh. [in his sermon of 13 June 1811.].

- McKenzie, Isabel (1935). Social Activities of the English Friends in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century. Priv. print. for the author. p. 32.

- LEWIS, Leyson (1856). Historical statement of the principles and practice of the British and Foreign School Society, etc. p. 23. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Connell, Philip (2005). Romanticism, Economics and the Question of 'culture'. Oxford University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780199282050. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Speck, William Arthur (2006). Robert Southey: Entire Man of Letters. Yale University Press. pp. 144–. ISBN 9780300116816. Retrieved 14 March 2018.