Joseph "Diamond Jo" Reynolds

Joseph Reynolds (June 11, 1819 – February 21, 1891) was an American entrepreneur and founder of the Diamond Jo Line, a transportation company which operated steamboats on the upper Mississippi River. In his youth, while still living in upstate New York, he operated a butchery, a general store, a grain mill, and a tannery.

Joseph Reynolds | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 11, 1819. |

| Died | February 21, 1891 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | "Diamond Jo" |

| Occupation | Entrepreneur |

| Known for | Diamond Jo Lines |

Reynolds established a successful leather-tanning operation in Chicago before becoming a grain trader in the upper-Mississippi River corridor. He acquired his own steamboats in order to improve access for his own grain shipments, and he eventually expanded to haul freight on the Mississippi River for other shippers. This fleet of river steamers grew into a company called the Diamond Jo Lines. He developed the Hot Springs Railroad in Arkansas. As a legacy, he established an endowment for the University of Chicago in order to build a clubhouse: the Reynolds Club, most recently used as a student union.

Early life

Joseph Reynolds was born June 11, 1819, in Fallsburg, New York to a large Quaker family. He only completed a grade school education. He started two ventures at a young age. First, he set himself up as a local butcher. At the age of seventeen, he and his brother Isaac established a general store in nearby Rockland, New York. He was married to Mary Morton, who was born about 1820 in Thunder Hill, Sullivan County, New York.[1] While he was still overseeing the operations of the mill, he bought out a nearby tannery. He reorganized and expanded the facilities, and was soon turning a profit selling leather.[1]

Moving west

Chicago

In 1855, Reynolds sold his businesses in Rockland and moved his family to Chicago. He started a tanning business on West Water Street. He traveled through Wisconsin and Minnesota, buying hides and furs.[1] He received the nickname "Diamond Jo" at this time. There was another J. Reynolds in the same business in Chicago, and their shipments became mixed. Joseph Reynolds conceived the idea of establishing a trademark. He marked his next shipment with his nickname "JO" enclosed within a diamond.[2] "Diamond Jo" was written by Reynolds without an "e" on Jo.[3]

Grain trade

In 1860, Reynolds sold his Chicago tannery and entered extensively into the grain business along the Mississippi, moving to McGregor, Iowa, and made his home there. Just one transportation company—the Minnesota Packet Company— hauled grain on that part of the Mississippi River, and Reynolds found that other shippers were given priority, while his grain languished and sometimes spoiled. In 1862, he entered the steamboat business to avoid losses to his cargo sitting at the docks. He commissioned the steamboat Lansing and hired a captain from Wisconsin. This allowed Reynolds to move his grain along the river to the railhead at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin on his own timetable. Then the Minnesota Packet Company made a deal with Reynolds: if he agreed to sell the 123-foot sternwheeler, they would extend better freight service to him in the future. He sold the Lansing. However, not much later, he built a 242-ton sternwheeler and two barges. He named the steamboat Diamond Jo.[1]

Transportation businesses

The Northwestern Packet Company, reorganized from the Minnesota Packet Company, approached Reynolds in regard to selling his fleet in 1862. Reynolds agreed and contracted with shipping companies to transport his grain for the next three years. In 1866, a new cartel of grain merchants was able to control shipping in the area, and Reynolds started building a new fleet of steamships. In 1867, he acquired some barges and the 61.5 ton steamboat John C. Gault. The next year he purchased three more steamers and a fleet of barges, calling his new company the "Chicago, Fulton, and River Line." In 1871, he added one more steamboat, Diamond Jo, after which many started referring to the company as the "Diamond Jo Line." Just as before, Reynolds acquired vessels to provide for his own shipping needs on a small segment of the upper Mississippi River. He continued to acquire more vessels, including tugboats and barges, and established a shipyard near Dubuque, Iowa.[1]

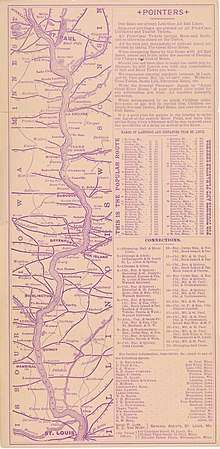

However, with this new enterprise, Reynolds increased the tonnage he hauled on behalf of other shippers, and expanded the scope of his river operations, running anywhere from St. Louis to St.Paul. During this expansion toward St. Louis, around 1880, he invested in larger steamboats. These included the sternwheelers Mary Morton (500 tons), Sidney (618 tons), and Pittsburg (722 tons). He continued to operate the shorter, lighter boats of his fleet upriver.[1]

In April 1875, Reynolds began building the Hot Springs Railroad between Malvern, Arkansas, and Hot Springs. The railroad was sometimes called the "Diamond Jo Line" for its developer.[4][5]

Death and legacy

Joseph and Mary Reynolds had one son named Blake who was born in McGregor their first year of residence there. Blake died during his late-twenties. Joseph and Mary Reynolds gifted a fountain and a park to the town of McGregor in memory of Blake.[1]

Reynolds died of pneumonia at the age of 71 in his room at the Congress Mine in Congress, Arizona.[6] After his death his estate was valued at between $8 and $10 million completely debt free. His estate included real estate, steam packets, grain elevators, mining properties in Arizona, California, Colorado, Kansas, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri, and the Hot Springs Railroad, a 24-mile-long (39 km) narrow gauge line running from Malvern, Arkansas, to Hot Springs, Arkansas.[7] He is buried at a family plot in Mount Hope Cemetery (Chicago) with his wife, Mary Morton Reynolds, and his son, Blake.[8]

Reynolds established an endowment with the University of Chicago to build the Reynolds Club, which as of October 2017, is still used as a student union.[9] This endowment included a scholarship fund. Construction started on the Tudor-style building in 1901 and was designed by the firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge. Originally planned as a library, the Reynolds Club included a billiard room, a bowling alley, and a theater.[10]

His wife, Mary Morton, inherited the Diamond Jo Line, and after she died in 1895, it was acquired by a partnership led by her brother.[5] In 1911, the steamboat fleet was sold to Streckfus Steamers.[11]

W. C. Handy includes a reference to the Diamond Jo Line in his song Saint Louis Blues, "You ought to see dat stove pipe brown of mine / Lak he owns de Dimon Joseph line."[12]

See also

- The Joseph "Diamond Jo" Reynolds Office Building and House in McGregor, Iowa is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Diamond Jo Boat Store and Office in Dubuque, Iowa.

References

- Thomas Wakefield Goodspeed (1922). "Joseph Reynolds". The University of Chicago Biographical Sketches, Volume 1. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 225–243. Archive.org.

- Palimpsest, State Historical Society of Iowa, April, 1970

- North Iowa Times newspaper, McGregor, Iowa, January 1, 1880

- Clifton E. Hull (1969). Shortline Railroads of Arkansas. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- "Diamond Jo Line". Encyclopedia Dubuque. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- "Diamond Jo's Death". Arizona Republican. Chronicling America. March 27, 1891. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- "Diamond Jo's Will". Arizona Republican. Chronicling America. March 26, 1891. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- "Joseph "Diamond Jo" Reynolds". Find A Grave. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- "Reynolds, Joseph "Diamond Jo"". Biographical Dictionary of Iowa. University of Iowa. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- David Allan Robertson (1916). The University of Chicago: An Official Guide. Third Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 58–62. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- William Howland Kenney. (2005). Jazz on the River. Chicago: University of Chicago. p. 19.

- "St. Louis Blues". Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto Libraries. 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

External links

- Diamond Jo Line Online Steamboat Museum: Dave Thomson Gallery.