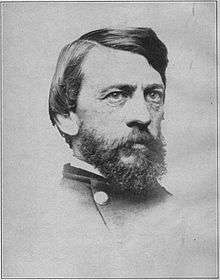

Jonathan Letterman

Major Jonathan Letterman[1] (December 11, 1824 – March 15, 1872) was an American surgeon credited as being the originator of the modern methods for medical organization in armies or battlefield medical management. In the United States, Letterman is known today as the "Father of Battlefield Medicine". His system of organization enabled thousands of wounded men to be recovered and treated during the American Civil War.

Jonathan Letterman | |

| Born | December 11, 1824 Canonsburg, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Died | March 15, 1872 (aged 47) San Francisco, California |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Service/ | Army of the Potomac |

| Years of service | 1849–1864 |

| Rank | Major |

| Relations | Mary Digges Lee Letterman (wife) |

| Other work | Coroner in San Francisco |

Early life

Letterman was born in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, the son of a well-known surgeon.[2] His studies were directed by a private tutor until he entered Jefferson College. He graduated from Jefferson in 1845 and Jefferson Medical College in 1849. That same year he was given the position of assistant surgeon in the Army Medical Department.

Letterman served in Florida during military campaigns against the Seminole Indians until 1853. He then spent a year in Fort Ripley, Minnesota. He was then ordered to Fort Defiance in New Mexico Territory to aid the campaign against the Apache. He was transferred to Fort Monroe in Virginia. From 1860 to 1861 he was engaged in California against the Utes.

His younger brother, William Henry Letterman, co-founded the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity with Charles Page Thomas Moore in Canonsburg after tending to sick classmates in Fall 1850.[3] After graduation from Jefferson College, William followed his brother into Jefferson Medical College.

Civil War

At the start of the Civil War, Letterman was assigned to the Army of the Potomac. He was named medical director of the Department of West Virginia in May 1862. A month later William A. Hammond, Surgeon General of the U.S. Army appointed him, with the rank of major, as the medical director of the Army of the Potomac itself.[4][5] Letterman immediately set to reorganizing the Medical Service of the fledgling army, having obtained from army commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan a charter to do "whatever necessary" to improve the system. The army reeled from inefficient treatment of casualties in the Seven Days Battles in June, but by the time of the Battle of Antietam in September, Letterman had devised a system of forward first aid stations at the regimental level, where principles of triage were first instituted. In other words, Letterman instituted standing operating procedures for the intake and subsequent treatment of war casualties and was the first person to apply management principles to battlefield medicine. He established mobile field hospitals to be located at division and corps headquarters. This system was connected by an efficient ambulance corps, established by Letterman in August 1862, under the control of medical staff instead of the Quartermaster Corps. Letterman also arranged an efficient system for the distribution of medical supplies.

Letterman proved the efficiency of his system at the Battle of Fredericksburg, in which the Army of the Potomac suffered 12,000 casualties, yet the command decisions of general officers in preparation for the later Battle of Gettysburg and during the Mine Run Campaign that followed that battle compromised Letterman's supply of medical equipment.[6][7] His system was, though, adopted by the Army of the Potomac and other Union armies after the Battle of Fredericksburg and was eventually officially established as the procedure for intake and treatment of battlefield casualties for the entirety of the United States' armies by an Act of Congress in March 1864.

The greatest casualties for the Army of the Potomac were suffered at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, but it also showed the efficiency of Letterman's system, since although the mortality rate of the Army of the Potomac had been 33% during 1862's Peninsular Campaign, the mortality rate after this bloody three-day battle was only 2%. No official report of the battle mentioned Letterman's contribution.[8] To deal with more than 14,000 Union wounded, along with 6,800 Confederate wounded who were left behind, a vast medical encampment was created northeast of Gettysburg off the York Pike on the George Wolf farm, named "Camp Letterman."[9] Of the Battle of Gettysburg and his system for treating casualties, Jonathan Letterman on October 3, 1863, reported to Brig. Gen. S. Williams, A.A.G., Army of the Potomac, "Surgeon John McNulty, medical director of that corps, reports that 'it is with extreme satisfaction that I can assure you that it enabled me to remove the wounded from the field, shelter, feed them, and dress their wounds within six hours after the battle ended, and to have every capital operation performed within twenty-four hours after the injury was received.' I can, I think, safely say that such would have been the result in other corps had the same facilities been allowed—a result not to have been surpassed, if equaled, in any battle of magnitude that has ever taken place.'"[10] Maj. McNulty, the medical director of the XII Corps (Union Army), either "had not received" or more likely had outright disobeyed orders to leave behind medical baggage wagons and, therefore, unlike many other Union medical commanders at Gettysburg had sufficient medical equipment and supplies to adequately implement Letterman's systems at Gettysburg for the XII Corps.[11]

A military man, Letterman understood that troop's lives are not saved just by the expedited treatment of their wounds, but, also, by their expedited travel and positioning. "The expediency of the order I, of course, do not pretend to question, but its effect was to deprive this department of the appliances necessary for the proper care of the wounded".[12] He appreciated that command had to make hard decisions when allocating transport vehicles for the best overall benefit of the Army's operations and soldiers. Still, Letterman was somewhat discouraged by command's lack of support for his organization at the Battle of Gettysburg and through the Mine Run Campaign.[13]

Unfortunately for Letterman's career, his mentor and superior officer, William A. Hammond, was undergoing censure as a result of his decision to ban the use of calomel, a mercury derivative, in May 1863. Although the decision was later proved scientifically correct, Hammond was ultimately court-martialed. After a brief period of serving as Inspector of Hospitals in the Department of the Susquehanna, Letterman resigned from the army in December 1864 well before the end of the American Civil War.

Railroad magnate Thomas A. Scott knew of Letterman's organizational abilities and administrative skill and offered him a job as general superintendent of a company exploring for oil in California. Letterman and his bride relocated to San Francisco, California, where that venture failed after about a year. Letterman than ran as a Democrat and was elected coroner, serving from 1867 to 1872.[14][15] He published his memoirs, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac, in 1866.

Death and legacy

After the death of his 38-year-old wife, Mary Digges Lee Letterman, from gastroenteritis, Letterman became severely depressed. They had met and married after the Battle of Antietam in western Maryland. Letterman then came down with several illnesses and eventually died in San Francisco. He was only 47 years old.

On November 13, 1911, the army hospital at the Presidio was named Letterman Army Hospital in his honor. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. The inscription on the private memorial that was erected for him reads:

Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, June 23, 1862, to December 30, 1863, who brought order and efficiency into the Medical Service and who was the originator of modern methods of medical organization in armies.

His wife was buried at his side. Her inscription reads: "Blessed are the dead that died in the Lord."

See also

- William Alexander Hammond

Notes

- The Arlington National Cemetery website lists his name as "Jonathan K. Letterman," but no other sources list a middle name or initial.

- Musto, p. 120.

- Phi Kappa Psi

- Appointment: Hammond's letter to Letterman, p. 3, at Google Books (19 June 1862)

- "Jonathan Letterman Correspondence and Diary 1860-1864". National Library of Medicine.

- Jonathan Letterman, M.D. (1866). Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. New York: D. Appleton & Co., p. 155

- House of Representatives (51st Congress, 1st Session). (1889). The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series 1, Vol. 27, Part 1, Misc. Doc. No. 146. (Robert N. Scott, Compiler). Washington, D.C.: United States government Printing Office, pp. 196-197 (Google digitized April 26, 2011)

- James Robertson, After the Civil War: the Heroes, Villains, Soldiers and Civilians who changed America(Washington D.C. National Geographic Press 2015) p. 131

- Musto, p. 125.

- House of Representatives (51st Congress, 1st Session). (1889). The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series 1, Vol. 27, Part 1, Misc. Doc. No. 146. (Robert N. Scott, Compiler). Washington, D.C.: United States government Printing Office, pp. 195-199 at p. 197, "No. 16", Report of Jonathan Letterman, U.S. Army Medical Director, Army of the Potomac, to Brig. Gen. S. Williams, A.A.G., Army of the Potomac, October 3, 1863(Google digitized April 26, 2011)

- Jonathan Letterman, M.D. (1866). Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. New York: D. Appleton & Co., p. 157

- House of Representatives (51st Congress, 1st Session). (1889). The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series 1, Vol. 27, Part 1, Misc. Doc. No. 146. (Robert N. Scott, Compiler). Washington, D.C.: United States government Printing Office, pp. 196 (Google digitized April 26, 2011)

- Jonathan Letterman, M.D. (1866)Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. New York: D. Appleton & Co., pp. 152-157

- Robertson p. 131

- Musto, p. 127.

References

- Early military medicine, U.S. Army Medical Department

- Clements, Bennett A. (1883). Memoir of Jonathan Letterman at Google Books. Reprinted from the Journal of the military service institution, G.P. Putnam's sons, vol. iv, no. 15, September 1883. 38 p.

- Greenwood, John T. (2003). Hammond and Letterman: A tale of two men who changed army medicine (PDF). Institute of Land Warfare. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- Letterman, Jonathan (1866). Medical recollections of the Army of the Potomac at Google Books. New York: D. Appleton

- Musto, R. J. "The Treatment of the Wounded at Gettysburg: Jonathan Letterman: The Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine," Gettysburg Magazine, Issue 37, 2007.

- Battle of Antietam biographical profile

- Biographical article at Arlington National Cemetery

- Camp Letterman

- Phi Kappa Psi