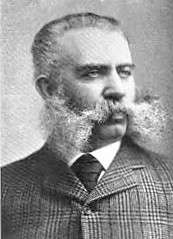

John Wolfe Ambrose

John Wolfe Ambrose (born in Newcastle West, Ireland on January 10, 1838) was a poor Irish immigrant boy who grew up to be a brilliant engineer and developer. Because of his efforts, channels within and leading into the New York Harbor were deepened and widened, to handle the largest transatlantic ships, thus allowing New York City's commercial economy to boom and compete in the world marketplace.

Early life

On August 22, 1851, 13-year-old John traveled from Queenstown, Ireland on the New York passenger ship, arriving in New York City with his mother, Bridget Wolfe Ambrose, and his siblings, Johanna, Thomas, Michael, Patrick, Mary, and infant Bridget. The family's patriarch, John Ambrose, had preceded the family's ocean journey to America, arriving in New York City in May 1851, on the ship Argo. John Wolfe Ambrose's older brother, James, immigrated on his own to America and went on to become a distinguished police constable in Staten Island, New York.

Education

Ambrose was educated at the Princeton Theological School (now Princeton University), with the intention of becoming a Presbyterian minister, but he left after only a year to attend the University of the City of New York (now New York University), which prepared him to become a leading civil engineer. By all accounts, he was quite a learned man, having studied mathematics and being fluent in four languages—English, Irish, Latin, and Greek. However, upon graduating in 1860, he decided to work as a newspaper reporter for the Citizens' Reform Association.

Career

A short time later, Ambrose became associated with a noted contractor, John Brown, who was responsible for the city's street cleaning. Under Brown's tutelage, Ambrose acquired the necessary knowledge of the Street Cleaning Department so that later when Mayor Hugh Grant decided to reorganize the Department, it was Ambrose who prepared a plan which was later adopted by the city. The plan involved subdividing the city into a district-block system, using uniformed street cleaners, and removing street garbage with hand carts.

This experience no doubt led to Ambrose's interest in improving and developing New York City. He set up his own contracting business and proceeded to accomplish some major pieces of work. Ambrose constructed all of the Second Avenue elevated railroad, from the Harlem River to Chatham Square, as well as part of the West Side elevated railroad between 75th and 189th Streets. He also laid the first eight miles (13 km) of pneumatic tubes in the United States under New York streets for Western Union Telegraph Company. In addition, he erected the gas works and laid ninety miles of gas mains for the Knickerbocker Gas Company. Between 1873 and 1880, he built many of Manhattan's uptown streets from Harlem swamp land.

In 1880, Ambrose became interested in developing Brooklyn's waterfront properties. Ambrose's life ambition involved a great scheme for developing New York. He set up the South Brooklyn Railroad & Terminal Company, the 39th Street South Brooklyn Ferry, and the Brooklyn Wharf & Dry Dock Company, all of which he was president. Ambrose's idea consisted of making the Battery become New York's great entrance and concentrating all of Long Island's railroad traffic to that area by means of his terminal railroad and ferry companies. Ambrose also hoped someday to construct six immense steamship piers, of varying lengths from 900 to 2,200 feet (670 m), to attract ocean liners to Brooklyn. Each pier was to have double railroad tracks between massive warehouses, along with a 5-acre (20,000 m2) storage yard. Although his scheme was never completely realized, as a consequence of his waterfront development in Brooklyn, large areas of farmland became a populous city neighborhood.

Because of his great scheme, Ambrose made his first trip to Washington, D.C. in 1881, to lobby Congress for money to dredge New York Harbor's inner channels, as well as deepen Sandy Hook Bar. Over the next fifteen years, Ambrose succeeded in obtaining $1,478,000 from Congress for improving the Bay Ridge and Red Hook channels. In 1898, after improving the inner harbor, Ambrose began urging the House of Representatives' Rivers and Harbors Committee for money to build an adequate channel starting at Sandy Hook, New Jersey and leading into the New York Harbor. The committee rejected his plan, but in the spring of 1899, just prior to his death, the Senate's Commerce Committee approved $6,000,000 for the project. The new channel made the shipping route shorter and safer, especially for the largest ships.

Personal life

Ambrose married Katharine (Kate) Weeden Jacobs (daughter of George Jacobs and Nancy Weeden) on July 1, 1860. The couple had five children: Katharine (Kate) Wolfe Shrady (1862-1945), John Fremont (1864-1933), Ida Virginia (1867-1933), Thomas Jefferson (1869-1926), and Mary (1872-1934). Only his daughter Kate and son John married, and only John had children (with wife Minnie Shrady, the sister of Kate's husband, George). The family lived in a townhouse at 575 Lexington Avenue, where both parents died. The entire family is buried together at Green-wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, along with George Shrady, Minnie Shrady, and Nancy Weeden.

Death

Ambrose died on May 15, 1899 from typhoid. He never lived to see the completion of the new channel, which occurred in 1907. (The Lusitania was the first ship to enter the channel in September 1907.) However, in recognition of his efforts, the New York State Legislature in 1900 officially expressed gratitude for Ambrose and named the channel and its lightship after him. Today, the Ambrose Channel still serves as the main entrance into New York Harbor for ocean vessels, and the Lightship Ambrose, a registered National Historic Landmark, is open to the public at Lower Manhattan's South Street Seaport Museum.

On June 3, 1936, the City paid tribute to one of its greatest Irish-immigrant sons. Before a crowd of 500 attendees, a memorial bust monument of Ambrose was erected in his honor and originally unveiled at Battery Park by his daughter, Katharine Wolfe Ambrose Shrady, and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Mayor La Guardia referred to Ambrose "as the pioneer of an idea. Mr. Ambrose was a man ahead of his time. He had vision and persistence to...continually press...his idea" (New York Times, June 4, 1936). Sadly, in November 1990, the bust was stolen and never recovered. However, in late 2017, the City Parks Department finally recreated a new bust and restored the monument, perhaps even surpassing its original beauty. On May 15, 2018—on the anniversary of Ambrose's death—the City held an official statue unveiling and rededication ceremony, which was attended by about 100 people, half of whom were descendants of Ambrose, traveling from eleven different states and Ireland. The newly-restored monument has been relocated from its original location of behind the old Aquarium to the edge of State Street, between Pearl and Water Streets, at The Battery.

Ambrose had the vision to see into the future enough to know that unless the New York Harbor was improved, New York would not be able to compete commercially in the world marketplace or remain an economic giant. Because of his efforts, John Wolfe Ambrose's futuristic vision of New York has been realized.

References

- "Ambrose Honored as Harbor Pioneer." The New York Times, June 4, 1936, p. 25:2.

- Ambrose, John Wolfe, "For New York Harbor: Liberal Appropriations Needed to Supply Commercial Demands." The New York Times, February 7, 1898, p. 8:1.

- "End of a Great Scheme." New York Daily Tribune, September 22, 1899.

- "John W. Ambrose Dead." The New York Times, May 17, 1899, p. 7:5.

- "John Wolfe Ambrose." The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. New York. James T. White & Co. 1935, Vol. 24, pp. 132–133.

- "Legislature's Tribute to J.W. Ambrose." The New York Times, April 13, 1900, p. 9:4.

- "Obituary: John W. Ambrose." New York Daily Tribune, May 17, 1899.