John Watson (philosopher)

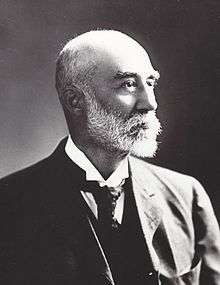

John Watson FRSC (1847–1939) was a Canadian philosopher and academic.

John Watson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 February 1847 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | 27 January 1939 (aged 91) |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Speculative idealism |

| Institutions | Queen's University |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Speculative idealism |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Life

John Watson was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on 25 February 1847. He attended the Free Church School in Kilmarnock, then enrolled at the University of Edinburgh. Within a month, however, he was drawn to the University of Glasgow by the reputations of the brothers John Caird, professor of divinity, and Edward Caird, professor of moral philosophy. On completion of his studies in 1872, he was appointed on the basis of the recommendation of his mentor Edward Caird to the Chair of Logic, Metaphysics, and Ethics at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario. Caird had written that "Watson is perhaps a man of the 'driest light' that I know. I do not know anyone who sees his way more clearly through any philosophical entanglements."[3] He spent the remainder of his career at Queen's and died in Kingston on 27 January 1939. Among his works are Kant and His English Critics, Christianity and Idealism, and The State in Peace and War.[4] He was the Gifford Lecturer for 1910–1912 at the University of Glasgow after which his lectures were published as The Interpretation of Religious Experience.[1] He was a charter member of the Royal Society of Canada.[5] Watson Hall at Queen's University is named after him.[6][7][8]

Philosophy

Watson's philosophy, which he called speculative or constructive idealism, continued the Hegelian critique of Immanuel Kant as pursued by Thomas Hill Green, Francis Herbert Bradley, and especially by his teacher at the University of Glasgow, Edward Caird. The main distinction between his position and that of Kant's critical idealism is that while both maintain that the universe is rational and that reason is self-harmonious, critical idealism denies that either of these propositions can be established on the basis of knowledge, while speculative idealism contends that the opposition of the theoretical and practical reason is fatal to both positions. While critical idealism falls back upon certain "postulates" of the moral consciousness in support of "faith", speculative idealism refuses to accept the antithesis of faith and knowledge, theoretical and practical reason, maintaining that a faith which is not identical with reason, a theoretical reason which is not in harmony with practical reason, is beset by an inherent weakness, which is sure to betray itself under the most searching of all tests, the test of self-criticism.[9]

All that exists is rational and in principle knowable. The degree to which it is known reflects both evolution and history. The human being possesses – as a result of evolution – a principle of rationality that makes it possible to comprehend the rationality of the world and to master it. Watson argued that this capacity could not, however, have resulted from natural selection.[10] By contrast, human evolution, especially as continued in history, represents a transcendence of nature, "the gradual realisation of reason in the individual and in society, and the gradual comprehension of the meaning of both when viewed in their relation to the world and God".[11]

Religion and moral philosophy

God is the absolute. The absolute is inadequately conceptualized as substance, power, person – although Watson found "personality" more fitting, though still inadequate – or super rational.[12] The. absolute is the identity of subject and object, the repository of universal reason itself, the very rationality that is manifest in the world and increasingly revealed to conscious, reflective human beings. Morality is acting rationally; and as reason ultimately governs both, there is no real conflict between individual and societal interests. Evil, or immorality, is the failure to act rationally owing to ignorance or confusion.[13] Watson's liberal theology had a significant influence on the Social Gospel movement and the formation of the United Church of Canada in 1925.[14]

Political theory

Watson's social thought is pervaded with a communitarianism deriving from his doctrine of the in-principle identity in reason of individual and common goods. Thus he summarizes his position on the State as existing "for the purpose of providing the external conditions under which all the citizens may have an opportunity of developing the best that is in them, and the success with which this aim is achieved is a test of the perfection of a community."[15][lower-alpha 1]

Works

- Kant and his English Critics:a comparison of critical and empirical philosophy Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1881.

- Schelling's Trascendental Idealism. A critical exposition. Chicago: S. C. Griggs and Company, 1882.

- Hedonistic Theories from Aristippus to Spencer Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1895.

- Christianity and Idealism: the Christian ideal of life in its relations to the Greek and Jewish ideals and to modern philosophy New York: The Macmillan Co., 1897. (Reprinted with additions, August, 1897.)

- The Philosophical Basis of Religion Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1907.

- The philosophy of Kant as contained in extracts from his own writings Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1908.

- The philosophy of Kant explained Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1908.

- An Outline of Philosophy Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1908.

- The Interpretation of Religious Experience (2 volumes) Gifford Lectures Volume 1 Volume 2 Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1912.

- The State in Peace and War Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1919.

- Selections from Kant Glasgow: Jackson Wylie & Co, 1927.

See also

Notes

- The book by Sibley, Northern Spirits, listed below under Further Reading offers a detailed assessment of Watson's political philosophy.

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Allen, Richard (2010). "Salem Goldworth Bland. Part 1: 19th Century Roots of Progressive Christianity" (PDF). Touchstone. 28 (1): 46. ISSN 0827-3200. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Wallace, Robert C., ed.: Some Great Men of Queens. Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1941, p. 24.

- http://www.jrank.org/literature/pages/8872/John-Watson.html

- Elizabeth A. Trott. "John Watson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- http://www.queensu.ca/campusmap/?mapquery=watson

- http://qnc.queensu.ca/Encyclopedia/w.html#Watson

- http://qnc.queensu.ca/Encyclopedia/j.html#JohnWatson

- Watson, J.: Philosophical Basis of Religion. Glasgow: Maclehose, 1907, p. 100.

- Watson, J.: Outline of Philosophy. Glasgow: Maclehose, 1908, pp. 143-144.

- Watson, J.: Christianity and Idealism(New Edition). Glasgow: Maclehose, 1897, p. 240.

- Christianity and Idealism, pp. 256-292.

- Outline of Philosophy, p. 229.

- Walsh, H. H.: The Christian Church in Canada. Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1956.

- Watson, J.: The State in Peace and War. Glasgow: Maclehose, 1919, p. 285.

Further reading

- Armour, Leslie; Trott, Elizabeth (1981). The Faces of Reason: An Essay on Philosophy and Culture in English Canada, 1850–1950. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-107-2.

- McKillop, A. B. A Disciplined Intelligence: Critical Inquiry and Canadian Thought in the Victorian Era. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1979.

- McKillop, A. B. Matters of Mind: The University in Canada, 1791–1951. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994.

- Sibley, Robert C. Northern Spirits: John Watson, George Grant, and Charles Taylor: Appropriations of Hegelian Political Thought. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2008.

- Rabb, J. D. Religion and Science in Early Canada. Kingston: Ronald P. Frye & Co., 1988.