John Thomson (physician)

Dr John Thomson FRS FRSE PRCPE (1765–1846) was a Scottish surgeon and physician, reputed in his time "the most learned physician in Scotland".[1] He was President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh from 1834 to 1836.

Early life

He was born in Paisley on 15 March 1765, the son of Joseph Thomson, a silk-weaver from Kinross, and his wife Mary Millar. worked as a boy under different masters for about three years, and at 11 he was bound apprentice to his father for seven years. At the end of his term of service his father intended him for the ministry, but was persuaded to apprentice him in 1785 to Dr. John White of Paisley, with whom he remained for three years.[1][2]

Thomson entered the University of Glasgow in the winter session of 1788–9, and the following year moved to Edinburgh. He was appointed assistant apothecary at the Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, in September 1790, and in the following September he became house-surgeon there, title surgeon's clerk, having already filled the port of assistant physician's clerk. He became a member of the Edinburgh Medical Society at the beginning of the winter session in 1790–1, and next year was elected one of its presidents. On 31 July 1792 Thomson, in poor health, resigned his appointment and went to London, where he studied at John Hunter's school of medicine in Leicester Square.[1]

On his return to Edinburgh, early in 1793, Thomson became a fellow of the College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, funded by James Hog, manager of the Paisley Bank. Until autumn 1798 he lived with the surgeon James Arrott, and attended the Royal Infirmary as a surgeon. During this time he studied chemistry, and ran a class during the winter of 1799–1800 which met in his home. In 1800 he was nominated one of the six surgeons to the Royal Infirmary under a reorganisation, and soon began teaching surgery. He also lectured in Chemistry. At this point he was living at Merchant Street in Edinburgh, close to Greyfriars Kirk.[3]

He also gave a course of lectures on for military surgeons; and visited London in the autumn 1803 to be appointed a hospital mate in the Army, a qualification to take charge of a military hospital in case of invasion.[1]

Edinburgh professor

The College of Surgeons of Edinburgh established a professorship of surgery in 1805, and, in spite of opposition, Thomson was appointed to the post. In 1806, at the suggestion of Earl Spencer, the Home Secretary, the King appointed him professor of military surgery in the University of Edinburgh. On 11 January 1808 Thomson obtained the degree of MD from the University and King's College, Aberdeen.[1]

In 1810 Thomson resigned his post at the Royal Infirmary, after the managers ignored criticism of his surgery by John Bell. He continued to lecture, however.[1]

He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1812.His proposers were John Playfair, Thomas Thomson and Sir George Steuart Mackenzie. He was further elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1824.[4]

In summer 1814 toured medical schools in Europe. He was admitted a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh on 7 February 1815: he was now acting as a consulting physician as well as a consulting surgeon. That summer he was again on the continent of Europe, and observed the treatment of the wounded after the Battle of Waterloo.[1]

In September 1815 Thomson was mainly instrumental in founding the Edinburgh New Town dispensary. He delivered a course of lectures on diseases of the eye in the summer of 1819, paving the way for the establishment of the first eye infirmary in Edinburgh in 1824. He was engaged during 1822–6 in the study of general pathology, and in 1821 he was an unsuccessful candidate for the chair of the practice of physic in the university, vacant after the death of James Gregory. In 1828–9 and again in 1829–30 he delivered a course of lectures on the practice of physic, both courses being given with his son, William Thomson (1802–1852).[1]

Last years

In 1831 Thomson addressed to Lord Melbourne, then secretary of state for the home department, a memorial on the advantages of a separate chair of general pathology. A commission was issued in his favour, and he was appointed professor of general pathology at Edinburgh, giving his first course of lectures in the winter session of 1832–3. Repeated attacks of illness compelled him to discontinue visits to patients after the summer 1835. He resigned his professorship in 1841: the duties had long been performed by deputy.

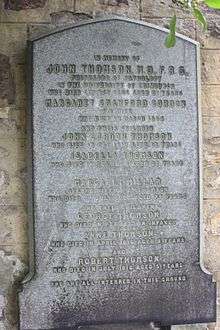

He died at Morland Cottage, near the foot of Blackford Hill on the south side of Edinburgh, on 11 October 1846.[1] He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in central Edinburgh. The grave lies in the western extension against the far west wall.

Works

Thomson wrote many pamphlets, and other works including:[1]

- The Elements of Chemistry and Natural History, to which is prefixed the Philosophy of Chemistry by M. Fourcroy, translated with notes, vol. i. Edinburgh, 1798, vol. ii. 1799, vol. iii. 1800; the work reached a fifth edition.

- Observations on Lithotomy, with a new Manner of Cutting for Stone, Edinburgh, 1808. An appendix was issued in 1810. The original work and the appendix were translated into French, Paris, 1818.

- Lectures on Inflammation: a View of the general Doctrines of Medical Surgery, Edinburgh, 1813; issued in America, Philadelphia, 1817, and again in 1831; translated into German, Halle, 1820, and into French, Paris, 1827. This influential series of lectures was based on the Hunterian theory of inflammation.

The smallpox epidemic of 1817–18 showed that vaccination was not as protective as had been supposed, and Thomson published views on the subject in two pamphlets of 1820 and 1822. He wrote a biography of William Cullen, and also edited The Works of William Cullen, M.D., Edinburgh, 1827, 2 vols.[1]

Family

Thomson was twice married: first, in 1793, to Margaret Crawford, second daughter of John Gordon of Caroll in Sutherlandshire; she died early in 1804; and secondly, in 1806, to Margaret, third daughter of John Millar. There were three children by the first marriage, the only survivor being William who went on to be Professor of Medicine at the University of Glasgow. From the second marriage Allen Thomson[1] and Margaret Mylne[5] outlived childhood.

He was grandfather to John Millar Thomson FRSE.

Notes

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. 56. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- John Thomson (1831). Lectures on Inflammation: Exhibiting a View of the General Doctrines, Pathological and Practical, of Medical Surgery. Carey & Lea. p. 294.

- Edinburgh and Leith Post Office Directory 1801-2

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- The biographical dictionary of Scottish women : from the earliest times to 2004. Ewan, Elizabeth., Innes, Sue., Reynolds, Sian. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 2006. ISBN 9780748626601. OCLC 367680960.CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

- Attribution

![]()