John R. Hamilton (architect)

John R. Hamilton was a nineteenth-century English and American architect, active between 1840 and 1870.

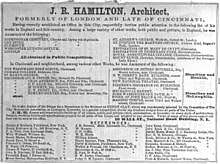

Hamilton had a significant practice in his native England before moving to North America in 1850. Between 1852 and 1859, in Cincinnati, Ohio, Hamilton's business thrived, with a long list of private homes, churches, and several major public buildings. He then moved to New York City, can be found in the American south as a traveling graphic journalist during and after the Civil War, and was again practicing architecture from New York in 1870.

Life

England

Hamilton first appears in 1841 as a new partner of Samuel Daukes (1811-1880). Daukes was established in practice in Gloucester and Cheltenham, designing for the rapidly developing railways. Among other commissions for mansions and churches, Daukes and Hamilton designed the main building of Royal Agricultural College near Cirencester, in Victorian Tudor style. Construction began in 1845.[1]

In 1848 the firm won a competition for the Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum, moved offices from the Midlands to London, took into the partnership James Medland (1808–94), and changed its name to Hamilton & Medland. (Daukes continued as an unnamed partner.) That firm is credited for Welford Road Cemetery in Leicester, Ford Park Cemetery in Plymouth, Warstone Lane Cemetery, Birmingham, and insane asylums in Lincoln and Powick Hospital in Worcester.[2]

Americas

Hamilton came to North America in 1850. A single source has an architect, with the same name, designing a residence for British emissary Louis Lewis in San Felipe, Panama in 1851.[3] The structure still stands on Plaza Simón Bolívar as the Simón Bolívar School in San Felipe.

Hamilton arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio in approximately 1852. In city business records he was listed on his own in 1853-1855, as partners with James C. Rankin, 1856–1857, and then with James W. McLaughlin in 1857-1858.

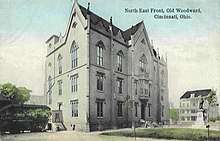

Hamilton's 1855 Woodward High School building stands among the first buildings in America to use terracotta for exterior decoration.[4] The historian of Cincinnati's schools noted that Hamilton had urged the adoption of terra cotta because of his extensive travels in Italy. "Unfortunately, however, its manufacture was then an untried process here, and within a few years it began to disintegrate in the walls of the structure, and it became necessary to cut it out and replace it with stone. This unfortunate state of affairs brought the building into disrepute. Nevertheless, as an architectural design, it was eminently satisfactory."[5]

Hamilton may have been in New York City at 36 Wall Street by 1859. According to Haverstock, page 369, "he served during the Civil War as special artist for Harper’s Weekly, traveling as far south as Port Hudson, Louisiana," and was in Richmond, Virginia, from about 1864 to 1866. In 1870 advertised his services from a New York office at 1267 Broadway.[6]

Hamilton was an early member of the Literary Club of Cincinnati (1857), and was made a Fellow of the fledgling American Institute of Architects on April 3, 1860.[7] Prominent Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford, also born in England but brought to the Cincinnati area as a child, got his start in Hamilton's office in 1857.

Henry Clay monument

In 1854 Hamilton entered and won a national design competition for the Henry Clay monument, to be built in Lexington Cemetery, Lexington, Kentucky. Hamilton's entry was accepted by the committee from more than 100 entries. The New York Times described it as,[8]

- a gothic temple of circular form with thirteen sides, intended to illustrate the thirteen original States of the Confederacy... The upper portion of the building is to be used as a record room to contain relics of the great statesman, an original and admirable idea. Altogether this will make the most complete and graceful mausoleum in the world.

Other sources noted it was to be "constructed entirely and innovatively of cast-iron". It was never built. Citing costs, the monument committee turned to a far more conventional column design by Julius W. Adams, a Lexington civil engineer and architect.[9]

Work

- Woodward High School building, 1855 (razed 1907)

- First Presbyterian Church, Aurora, Indiana, which Hamilton designed for the Gaff family in a Greek Revival Style, 1855[10]

- Saint Mary's Episcopal Church, Hillsboro, Ohio, 1855[11]

- the (new) National Theater on Sycamore Street, 1857

- Masonic Temple, NEC Third and Walnut, 1859[12]

- Institute of Fine Arts (razed), 625 Broadway, New York City, for the Dusseldorf Gallery of Art, 1860[13]

- Derby's Building (razed), southwest corner of Third and Walnut,[14] date unknown

- University Club, formerly the Edmund Dexter Mansion, NEC Fourth and Broadway streets, Cincinnati

- First Presbyterian Church, 1101 Bryden Rd, Columbus, Ohio, which "survives with its terracotta exterior elements"

References

- Historic England. "Royal Agricultural College - Cirencester (1187418)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Curl, James Stevens; Wilson, Susan (2015). The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 342. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- The Panama Star of 30 September 1851, quoted in "El Casco Antiguo de la Ciudad de Panamá". libropanama. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- according to an article in the “Editor’s Bureau” in The Horticultural Review and Botanical Magazine, IV (1854), 428-429.

- Shotwell, John B. (1902). A History of the Schools of Cincinnati. The School Life Company. p. 319. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Real Estate Record and Builder's Guide, Volumes 5-6. F.W. Dodge. 1 January 1870. p. 19. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- by 1880 Hamilton's membership had lapsed; see Clark, editor, T.M. (1881). Proceedings of the 14th Annual Convention of the American Institute of Architects. Alfred Mudge & Son. p. 42. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "The Clay Monument" (PDF). New York Times. 16 June 1855. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "The Henry Clay Monument". Lexington Cemetery. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- First Presbyterian Church, NRHP Nomination Form, 1994, at https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/356fb8a9-132a-44f3-90fb-c9c4f1879fb3?branding=NRHP

- Ohio Historic Places Dictionary, Volume 2. North American Book Dist LLC. 1 January 2008. p. 771. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Kenny, Daniel J. (1 January 1879). Cincinnati Illustrated: A Pictorial Guide to Cincinnati and the Suburbs. Robert Clarke & Co. p. 73. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Irish Builder and Engineer, Volumes 1-3. Howard MacGarvey & Sons. 1 May 1860. p. 249. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- Williams' Cincinnati (Hamilton County, Ohio) City Directory. Williams Directory Company. 1 January 1860. p. 30. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John R. Hamilton. |