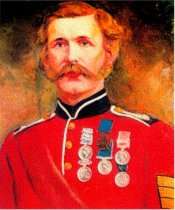

John Prettyjohns

John Prettyjohns VC (sometimes misspelled Prettyjohn) (11 June 1823 – 20 January 1887) was the first Royal Marine to win the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

John Prettyjohns | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 June 1823 Dean Prior, Devon |

| Died | 20 January 1887 (aged 63) Chorlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Royal Marines |

| Years of service | 10 June 1844 – 16 June 1865 |

| Rank | Colour-Sergeant |

| Unit | Royal Marine Light Infantry |

| Battles/wars | Crimean War Second Anglo-Chinese War |

| Awards | Victoria Cross |

| Other work | Golf Club steward |

Early life

Prettyjohns was born at Dean Prior near to Buckfastleigh, Devon to William Pethyjohns (1800-1889) and his wife Margaret (nee Pow, ABT 1805-1866). His early years were spent labouring in Buckfastleigh. On 10 June 1844 he enlisted as a private, 59th Company, Plymouth Division, for unlimited service - and collected 2s 6d for attestation. On the following day, he collected a bounty of £3 17s 6d for oath of allegiance. He embarked on HMS Melampus to south-east America and East Indies on 22 March 1845, being flogged for an unknown misdeameanour on 28 June. He disembarked at Chatham on 23 August 1849, and joined HMS Bellerophon on 7 November 1850. On this ship, he embarked for the Mediterranean in January 1852, being promoted to corporal on 15 January. On 17 October 1854, HMS Bellerophon bombarded Sevastopol during the Crimean campaign.

Details

On 5 November 1854, Corporal John Prettyjohns won the Victoria Cross during the Battle of Inkerman.

The 2 November 1854 was an active day, 312 rank and file marched off from the heights of Balaklava, for the Light Division, under the command of Captain Hopkins, RMLI, the detachment was divided into four companies, taking turn in the trenches. On the morning of the 5th, the relief, which had just returned, were preparing their rude breakfast; the firing from Sebastopol was gradually increased, and then commenced in our rear. Nothing could be distinguished but fog and smoke from where we were.

The bugle sounded the ‘Fall-in’ at the double, and officers were flying about giving orders, saying vast columns of the enemy were moving up to our rear. The roll of musketry was terrific; we were advanced cautiously until bullets began to fall in amongst us, the Sergeant-Major was the first man killed; order given to lay (sic) down; it was well we did so; a rush of bullets passed over us: then we gave them three rounds, kneeling, into their close columns.

At the same time some seamen opened fire from some heavy guns into their left flank, and this drove them back into the fog and smoke. Our Commanding Officer received several orders from mounted officers at this critical time; first it was ‘advance’, then it was ‘hold your ground and prevent a junction or communication with the town’.

The Inkermann Caves were occupied by the enemy’s sharpshooters, who were picking off our officers and gunners; between us and these men was an open space exposed to the broadside fire of a frigate in the harbour under shelter of the wall, but she had been heeled over so as to clear the muzzles of her guns, when fired, from striking the wall; thus, her fire raked the open part. The Caves were to be cleared, and the Marines ordered to do it; as soon as we showed ourselves in the open, a broadside from the frigate thinned our ranks; Captain March fell wounded. Captain Hopkins ordered his men to lie down under a bit of rising ground, and ordered two privates, Pat Sullivan and another man to take the Captain back, and there he stood amidst a shower of shot and shell, seeing him removed.

A division under Sergeant Richards and Corporal Prettyjohns, was then thrown out to clear the caves, what became of the Commanding Officer and the others I never knew, so many statements have been made.

We, under Richards and Prettyjohns, soon cleared the caves, but found our ammunition nearly all expended, and a new batch of the foe were creeping up the hillside in single file, at the back. Prettyjohns, a muscular West Countryman, said, ‘Well lads, we are just in for a warming, and it will be every man for himself in a few minutes. Look alive, my hearties, and collect all the stones handy, and pile them on the ridge in front of you. When I grip the front man you let go the biggest stones upon those fellows behind’.

As soon as the first man stood on the level, Prettyjohns gripped him and gave him a Westcountry buttock, threw him over upon the men following, and a shower of stones from the others knocked the leaders over. Away they went, tumbling one over the other, down the incline; we gave them a parting volley, and retired out of sight to load; they made off and left us, although there was sufficient to have eaten us up.

Later in the day we were recalled, and to keep clear of the frigate’s fire had to keep to our left, passing over the field of slaughter.

On being mustered, if my memory is not at fault, twenty-one had been killed and disabled, and we felt proud of our own Commanding Officer, who stood fine, like a hero, helping Captain March.

Corporal Prettyjohns received the VC, Colour Sergeant Jordan the Medal and £20 for Distinguished Conduct in the Field, Captain Hopkins a C.B., others were recommended.— - a report by Sergeant Turner RM

CORPORAL JOHN PRETTYJOHNS, RM

Reported for gallantry at the Battle of Inkerman, having placed himself in an advanced position; and noticed, as having himself shot four Russians.

- Despatch from Lieutenant Colonel Hopkins, Senior Officer of Marines, engaged at lnkerman

London Gazette 24 February 1857[1]

HMS Agamemnon, Crimea

On 5th November 1854 at the Battle of Inkerman, Corporal Prettyjohn's platoon went to clear out some caves which were occupied by snipers. In doing so they used up almost all of their ammunition, and then noticed fresh parties of Russians creeping up the hill in single file. Corporal Prettyjohn gave instructions to his men to collect as many stones as possible which they could use instead of ammunition. When the first Russian appeared he was seized by the corporal and thrown down the slope. The others were greeted by a hail of stones and retreated.

- letter from Colonel Wesley, Deputy Adjutant General

On 16 January 1856, he was promoted to sergeant and embarked on HMS Sans Pareil for Hong Kong on 12 March 1857. He was promoted to Colour-Sergeant on 29 April, and on 26 June a VC was sent to the Admiralty and despatched to China for presentation. On 16 July, he sailed for Singapore and Calcutta on HMS Shannon, arriving in Fort William, Calcutta later that year. On 28 December he took part in the capture of Canton before embarking on HMS Tribune for Vancouver and San Juan Island. On 17 December 1863 his final tour of duty came to an end. He was discharged on 16 June 1865 after 21 years and 6 days service - 16 years 94 days of which were spent at sea or abroad.

He retired to the Greater Manchester area, and became a Golf Club steward at Whalley Range Bowling Club, Albert Road, Withington, Lancashire. He died on 20 January 1887 at Chorlton upon Medlock, Lancashire and is buried in the Southern Cemetery, Manchester.

The awards

Corporal Prettyjohns was awarded the Victoria Cross, British Crimea Medal with clasp for Balaclava, Inkerman and Sebastopol, the Turkish Crimea and Sardinian Crimea Medals, the China Medal (1857) with clasps for Canton, a Long Service & Good Conduct medal, and a Long Service and Good Conduct gratuity for gallantry in the Crimea.

Family

On 10 February 1850, John married his first cousin, Elizabeth Prettyjohns (7 May 1826 – 19 August 1912), at Plymouth Register Office. They had two children:

- Elizabeth (Bessie) Prettyjohns (1857 – 13 July 1889)

- Alice Maud Prettyjohns (28 February 1865 – 4 July 1960)

Legacy

The Royal Marines hold a procession each autumn to honour the memory of Corporal Prettyjohns.

The medal

His Victoria Cross and other medals are displayed at the Royal Marines Museum, Southsea, England.

References

- "No. 21971". The London Gazette. 24 February 1857. p. 654.