John Mylne (died 1667)

John Mylne (1611 – 24 December 1667), sometimes known as "John Mylne junior", or "the Younger", was a Scottish master mason and architect, who served as Master Mason to the Crown of Scotland. Born in Perth, he was the son of John Mylne, also a master mason, and Isobel Wilson.

John Mylne | |

|---|---|

John Mylne, painted by an unknown artist around 1650 | |

| Born | 1611 Perth, Scotland |

| Died | 24 December 1667 |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Tron Kirk, Edinburgh Cowane's Hospital, Stirling Panmure House, Angus |

Practising as a stonemason, he also took on the role of architect, designing as well as building his projects. He was one of the last masters of Scottish Renaissance architecture, before new styles were imported by his successors.[1] Alongside his professional career, he also served as a soldier and politician. He married three times but had no surviving children.[1]

Career

Mylne learned his trade from his father, assisting him with projects including the sundial at Holyrood Palace. In 1633 Mylne was made a burgess of the royal burgh of Edinburgh, and was admitted to the Edinburgh lodge of masons, both due to his father's position.[1] He was first appointed to the town council in 1636 and, in the same year, was appointed master mason to the Crown, succeeding his father.[1]

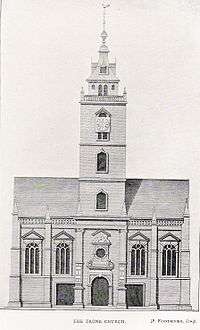

His building projects were concentrated in Edinburgh, where, from 1637, he served as principal master mason to the city. For ten years he was involved in the construction of the Tron Kirk on the High Street, which opened in 1647. The Tron was built to house the congregation of St Giles', which had been raised to cathedral status, and was laid out in the new T-plan form with the pulpit in the centre, to suit reformed worship. The design was informed by contemporary Dutch architecture and, in particular, by the work of Hendrick de Keyser whose Architectura Moderna showcased his church designs in the Netherlands.[2] Mylne worked on the building with master wright John Scott who was responsible for the timber work. The building was executed in a Dutch influenced style with both gothic and classical details. The church was not fully complete before Mylne's death and was subsequently remodelled in the 18th century. A new spire was added in the 19th century following a fire, but Mylne's work can be seen in the body of the kirk. The carved tympanum was executed by Mylne's brother Alexander.[3]

From 1637 to 1649 he was also engaged on the design of Cowane's Hospital in Stirling, which was executed by Stirling mason James Rynd. Mylne also carved the statue of its founder for the facade.[4] In 1642, Mylne surveyed the crumbling remains of Jedburgh Abbey, for which services he was made a burgess of Jedburgh. He built the choir, steeple, and north aisle of Airth Old Church, commencing 15 July 1647.[5]

From 1643 to 1659, he served as master mason for the construction of Heriot's Hospital (now a school), succeeding William Aytoun. The building had been started in 1628 by William Wallace, and would not be finally completed until 1700; Mylne rebuilt one or two of the towers in 1648.[6] Also in 1648, Mylne was engaged to repair the crown steeple of St. Giles'.[7]

Projects in the 1650s included the building of fortifications in Leith, and the addition of artillery emplacements to Edinburgh's town wall.[8] He undertook a division of Greyfriars Kirk, to serve two congregations, and constructed a professor's house for Edinburgh University, which was demolished in the 18th century.[1]

Following the Restoration of Charles II, Mylne was reconfirmed in his post of Royal Master Mason, and was commissioned in 1663 to survey the upper floors of Holyrood Palace. The resulting plans are the earliest surviving architectural drawings from Scotland, and are held in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.[9] His design for the completion of the palace went unexecuted, with the work eventually being carried out by Sir William Bruce in the 1670s.[1]

In 1666 John Mylne designed and was engaged to build Panmure House, near Forfar, for the 2nd Earl of Panmure. After his death, the work was continued by Alexander Nisbet, possibly with the assistance of William Bruce.[10] This house, demolished in 1950, resembled Heriot's Hospital and other Scottish 17th-century buildings, rather than looking forward to the new classical styles which would be introduced by Bruce.[1] During the Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1665–1667, Mylne designed and built fortifications at Lerwick, which were later reconstructed as Fort Charlotte.[1] He provided a design for Linlithgow's tolbooth in 1667, but following his death another mason was sought, and a different design built. Another scheme was for Leslie House, carried out after his death by Robert Mylne, again with the advice of Bruce.[11]

Mylne's architectural works are in the Scottish Renaissance tradition, which combined gothic and classical elements, together with mannerist ornament, often derived from imported pattern books.[12] Colvin describes Mylne as "the leading master of the last phase of Scottish mannerism".[13] By the 1660s, Mylne's work was becoming old-fashioned, as the European-inspired Palladian began to be imported by William Bruce.[14]

Political and military service

In 1640, Mylne joined the Scottish army which invaded northern England during the Second Bishop's War. He was promoted in 1646 to Captain of Pioneers, and Master Gunner of Scotland.[1]

As well as serving on Edinburgh's town council from 1636 to 1664, Mylne played several other political roles in his life. In 1652, he served as part of a commission sent to the English Parliament in London, to discuss a possible Treaty of Union.[1] From 1654 to 1659 he represented Edinburgh at the Convention of Royal Burghs, and in 1662 he was elected a burgh commissioner for Edinburgh, attending Charles II's first Scottish parliament.[1]

Death

In 1667 Mylne was in discussions with the town of Perth for construction of a new market cross.[15] However, he died at Edinburgh in December. He was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, where a monument, erected by his nephew and apprentice Robert Mylne, still stands. Another memorial was erected by the Freemasons at their meeting place, St. Mary's Chapel, although this former church was demolished in the 18th century.[16] His portrait hangs in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Robert Mylne succeeded him as master mason to the crown.

Notes

- Colvin, p.569-70

- Howard, p.192

- Gifford, et al., p.174

- Colvin, p.569-70, Gifford & Walker, p.707-8

- Contract of June 1647 in National Archives NAS GD156/8

- Colvin, p.569-70, Gifford, et al., p.179-82

- Colvin, p.569-70, Gifford, et al., p.109

- Gifford, et al., p.84

- Howard, p.213

- Glendinning, et al., p.90

- Glendinning, et al., p.83

- Howard, p.218

- Colvin, p.570

- Glendinning et al., p.97

- DNB, Vol.14, p.4

- Colvin, p.569-70, Gifford, et al., p.37. The chapel, formerly a church, stood off the Royal Mile, and was demolished to make way for the South Bridge.

References

- Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 1921–22

- Colvin, Howard (1978) A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects, 1600–1840, John Murray

- Gifford, John (1984) McWilliam, Colin & Walker, David, The Buildings of Scotland: Edinburgh, Penguin

- Gifford, John, & Walker, Frank Arneil (2002) The Buildings of Scotland: Stirling and Central Scotland, Penguin

- Glendinning, Miles, MacInnes, Ranald, & MacKechnie, Aonghus (1996) A History of Scottish Architecture, Edinburgh University Press

- Howard, Deborah (1995) Architecture of Scotland: Reformation to Restoration, 1560–1660, Edinburgh University Press

- McEwan, Peter J. M. (1994) Dictionary of Scottish Art and Architecture, Antique Collectors' Club

External links

- Gazetteer for Scotland entry on John Mylne

- Panmure House brief history, plans and old photographs.