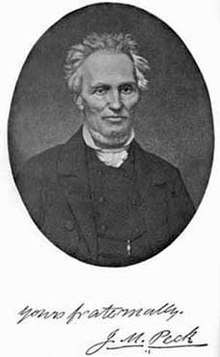

John Mason Peck

John Mason Peck (1789–1858) was an American Baptist missionary to the western frontier of the United States, especially in Missouri and Illinois. A prominent anti-slavery advocate of his day, Peck also founded many educational institutions and wrote prolifically.

Biography

Born in Litchfield, Connecticut to a farming family, Peck received little formal education but in 1807 began to teach school. He was converted to Christianity at a revival at his Congregational Church.

Marriage and family

On May 8, 1809, Peck married Sally Paine, a native of New York state, whom he met in Litchfield. In 1811 the couple moved from Connecticut to Greene County, New York, near her family's home. Shortly after the birth of their first son, they joined the Baptist Church, in a mission from the New Durham, New Hampshire church.[1] Peck taught school and soon also served as pastor at the Baptist churches in Catskill and Amenia, New York. He became interested in missionary work after meeting Luther Rice, and went to Philadelphia to study under William Staughton while awaiting assignment.[2] There, Peck met James Ely Welch, who became his missionary partner.

Career

Having secured funding as "missionaries to the Missouri Territory," the Peck and Welch families traveled westward, arriving in St. Louis in December, 1817. Peck and Welch organized the First Baptist Church of St. Louis, the first Protestant church in the city, and baptized two converts in the Mississippi River in February, 1818.[3] By year's end, they also soon founded the first missionary society in the West: The United Society for the Spread of the Gospel. In 1820, the Triennial Convention, short of funds and convinced ministerial migration would continue, discontinued their missionary support. Peck refused to move back East or north to work with Isaac McCoy among Native Americans. Instead, he continued his itinerant ministry and church-planting efforts around St. Louis independently. Two years later, the Massachusetts Baptist Mission Society employed Peck at $5.00 a week while conducting missions. Meanwhile, the St. Louis Baptists built a building with the Western Baptist Society on the first floor, and a meeting hall above (which they shared with Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian and other Protestant denominations).

Peck became active in establishing Bible societies and Sunday School associations. Distributing Bibles "silently undermine[d] the opposition to missions" of geographically stable preachers such as Daniel Parker, as well as spread literacy and Christian principles (including temperance and opposition to slavery) among the dispersed rural population. Peck moved to Rock Springs, Illinois in 1822 to farm, and arranged a circuit to visit the various societies which he continued to establish, as well as isolated farms. On one trip, Peck visited Daniel Boone, then nearly 80, and later wrote a book about the frontiersman's life.

In 1824 Peck's preaching helped Illinois Governor Edward Coles defeat efforts to revise Illinois' constitution to permit slavery. Four years later, black Baptists in St. Louis sought to establish their own church, and with Peck's help they established the African Church of St. Louis (later renamed the First Baptist Church of St. Louis). Of the original 220 members, 200 were slaves. Peck ordained a young freeman, John Berry Meachum, as their pastor.[4] When that church's members voted themselves out of existence, Peck helped establish the Second Baptist Church in 1833, serving as its interim minister three times in the 1840s.

Convinced that Baptists could not rise without educated preachers, Peck founded a seminary at his Rock Springs farm near O'Fallon, Illinois, but his first attempt to secure a charter failed because of opposition by an anti-mission preacher/legislature. Undeterred, Peck moved his new school to Upper Alton, Illinois. In 1836, after a significant contribution from Benjamin Shurtleff, M.D. of Boston, it became Shurtleff College, which became part of the Southern Illinois University system in 1957.[5] Peck then established the Illinois Baptist Education Society, serving as its first secretary.

The American Baptist Home Mission Society was organized in 1832, under Peck's influence, with Jonathan Going (sent from Massachusetts at his request the previous year) as the first secretary. This society, like Peck, directed its efforts toward the people of the frontier: Settlers, Native Americans and later former Confederate slaves.

Peck also helped establish the Illinois State Baptist Convention in 1834, and became its first president. He wrote prolifically, including on agriculture, frontier history and Native American matters. In 1843 he founded the American Baptist Publication Society. Peck also established a weekly religious journal, the Western Pioneer. Harvard University awarded Peck an honorary degree in 1852.[6] Two years later, Illinois' legislature commissioned him to write the first history of the state. Peck also founded the Western Baptist Historical Society, and briefly served in Covington, Kentucky.[7]

Death and legacy

During his 40-year ministry, Peck contributed to the establishment of 900 Baptist churches, saw 600 pastors ordained and 32,000 were added to the Baptist faith. He died in Rock Springs, Illinois, where he was first buried. His body was reinterred at Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis.[8]

References

- http://www.newdurhamchurch.com/about_us/history/

- "Biographies: John Mason Peck", Southern Baptist Historic Library and Archives, accessed 6 Sept 2013

- http://2ndbc.org/safari/article/65.html

- http://2ndbc.org/safari/article/65.html

- http://www.lib.niu.edu/1998/ihy981205.html

- http://2ndbc.org/safari/article/65.html

- http://www.sbhla.org/bio_peck.htm

- "Biographies: John Mason Peck", Southern Baptist Historic Library and Archives, accessed 21 Aug 2010

Further reading

- Hayne, Coe. Vanguard of the Caravans: A Life Story of John Mason Peck, 1931.

- Lawrence, Matthew. John Mason Peck, the Pioneer Missionary: a Biographical Sketch, 1940.

- Ross, Ryan A. "John Mason Peck Loses His Moral Progress: The Story of a Private Library Fire at Rock Spring, Illinois," Journal of Illinois History 15:2 (Summer 2012), 89-106.

External links

- Southern Baptist Historical Library

- Works by John Mason Peck at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Mason Peck at Internet Archive

- John Mason Peck at Find a Grave

- John Cushman Abbott Exhibit Supplement—includes a discussion of Peck and his books A Guide for Emigrants and A Gazetteer of Illinois, and downloadable pdf files of the books.