John Keep

Rev. John Keep (20 April 1781 – 11 February 1870) was a trustee of Oberlin College from 1834 to 1870. Keep and William Dawes toured England in 1839 and 1840 gathering funds for Oberlin College in Ohio.[1] They both attended the 1840 anti-slavery convention in London.[2]

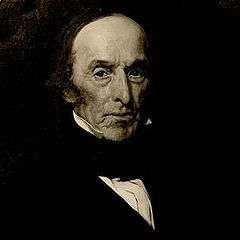

Rev. John Keep | |

|---|---|

Reverend Keep in 1859 | |

| Born | 1781 |

| Died | 1870 |

| Occupation | Reverend |

| Known for | Abolitionism |

Early life and career

Keep was born, 20 April 1781, in Longmeadow, then a precinct of Springfield, Mass. Of a family of nine children he was the seventh. He graduated from Yale College in 1802. For a year after he was graduated he taught a school in Bethlehem, Conn., reading theology at the same time with the pastor, Rev. Dr. Azel Backus. He continued his theological course for another year with Rev. Asahel Hooker, of Goshen, Conn., and was licensed by Litchfield North Association, 11 June 1805. The next Sunday he preached in the Congregational Church in Blandford, Mass., and immediately received an invitation to settle, which he accepted. Here he remained for 16 years. In May, 1821, he removed to the Congregational Church in Homer, N. Y., and was installed November 7. In 1833 he resigned in consequence of disaffection caused by his sympathy with the "new measures" of revivalists. For the following year he preached in the Presbyterian Church in Cleveland, Ohio, and then organized the First Congregational Church in Ohio City, (now Cleveland, West Side,) and became its pastor.

![]()

Oberlin College

In 1834, Keep was elected a Trustee of Oberlin College. Keep was renowned for championing the values that Oberlin College eventually became renowned for. He championed rights for women, black students and missionary zeal.[3] Keep was the person who cast the deciding vote in 1835 that allowed black students to enter Oberlin College in Ohio.[4]

Keep and William Dawes both undertook a fund raising mission in England in 1839 and 1840 to raise funds from sympathetic abolitionists. Oberlin College was one of the few multi-racial and co-educational colleges in America at that time.[4] The appeal was carefully written and supported by leading American abolitionist like William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Grew, Henry Brewster Stanton and Wendell Phillips.[5]

- ^ The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, Given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880

Both Keep and Dawes are credited with helping to start the collection of African Americana at Oberlin College which inspired other writers.[6] Keep appears in the large painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon which is on permanent display at London's National portrait gallery although he is obscured by other convention attendees.[7] The people that Keep corresponded with, John Scoble, Joseph Sturge and George Thompson, and who welcomed them in London are clearly in the picture.

When Keep returned to Oberlin they had raised $30,000.[5] Keep became the "father" to the girls at the college who lived at his house. Keep died in 1870 and in 1889 the house was bought by the college. His house was used as a dormitory for female "indigent" students until it was rebuilt in 1912. The rebuilding was funded by Keep's granddaughter who commissioned Normand Patton to design Keep Cottage to sleep 80 women with room for 110 to dine. In 1966 the rules were changed to allow co-educational dormitories.[3]

References

- The culture of English antislavery, 1780-1860, David Turley, p192, 1991, ISBN 0-415-02008-5, accessed April 2009

- The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, accessed April 2009

- Blodgett, Geoffrey (1985). Oberlin architecture, college and town: a guide to its social history p.22. p. 239.

- Oberlin Digital Collections, accessed April 2009

- Weld, Theodore Dwight; et al. "An Appeal on Behalf of the Oberlin Institute In Aid of the Abolition of Slavery, In the United States of America by Theodore Dwight Weld". Oberlin College. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Bibliophiles and Collectors of African Americana, Charles L. Bronson, accessed April 2009