John Jackson (controversialist)

John Jackson (1686–1763) was an English clergyman, known as a controversial theological writer.

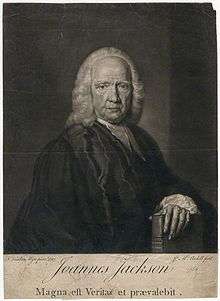

John Jackson | |

|---|---|

John Jackson, 1757 mezzotint by James Macardell after Frans van der Mijn | |

| Born | 4 April 1686 Sessay |

| Died | 12 May 1763 (aged 77) Leicester |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Cambridge |

| Academic work | |

| School or tradition | controversialist |

Life

Jackson was born at Sessay, near Thirsk in the North Riding of Yorkshire on 4 April 1686, eldest son of John Jackson (died 1707, aged about 48), rector of that parish. His mother's maiden name was Ann Revell.

He attended Doncaster grammar school, after which he entered Jesus College, Cambridge in 1702,[1] and went into residence at midsummer 1703. He studied Hebrew under Simon Ockley. Graduating B.A. in 1707, he became tutor in the family of Simpson, at Renishaw, Derbyshire. His father had died rector of Rossington, West Riding of Yorkshire, and this preferment was conferred on Jackson by the corporation of Doncaster on his ordination as a deacon in 1708, and as a priest in 1710.[2]

In 1718, Jackson went to Cambridge for his M.A.; the degree was refused on the ground of his writings respecting the Trinity. The following year he was presented by Nicholas Lechmere, chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, to the confratership of Wigston's Hospital, Leicester. Samuel Clarke held the mastership of the hospital, and recommended Jackson. The post did not involve subscription to the Thirty-nine Articles, and carried with it the afternoon lectureship at St. Martin's, Leicester, for which Jackson, who removed from Rossington to Leicester, received a licence on 30 May 1720 from Edmund Gibson, as bishop of Lincoln. On 22 February 1722 he was inducted to the private prebend of Wherwell, Hampshire, on the presentation of Sir John Fryer; here also no subscription was required. The mastership of Wigston's Hospital was given to him on Clarke's death (1729) by John Manners, 3rd Duke of Rutland, chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Several presentments had previously been lodged against him for heretical preaching at St. Martin's, and when he wished to continue the lectureship after being appointed master, the vicar of St. Martin's succeeded (1730) in keeping him out of the pulpit by somewhat forcible means.[2]

In 1730 Benjamin Hoadly offered him a prebend at Salisbury Cathedral on condition of subscription, but after the 1721 publication of Daniel Waterland's Case of Arian Subscription he had decided to subscribe no more. In September 1735 he went to Bath, Somerset for the benefit of a dislocated leg. On 28 September he preached at St. James's, Bath, at the curate's request. Dr. Coney, the incumbent, preached on 12 October, and refused the sacrament to Jackson, on the plea that he did not believe the divinity of Christ. Jackson complained to the bishop John Wynne, who disapproved of Coney's action.[2]

He married Elizabeth, daughter of John Cowley, a collector of excise at Doncaster, in 1712, and they had twelve children. Elizabeth died in 1760. Jackson himself died at Leicester on 12 May 1763. His son John and three daughters (all married) survived him.

Works

Jackson was prompted to take on controversial topics by the publication (1712) of the Scripture Doctrine of the Trinity by Samuel Clarke. His first publication was a series of three letters, dated 14 July 1714, by 'A Clergyman of the Church of England,' in defence of Clarke's position. He corresponded with Clarke, and made his personal acquaintance at King's Lynn. Jackson's theological writings were anonymous; he acted as a mouthpiece for Clarke, who kept in the background after promising Convocation, in July 1714, to write no more on the subject of the Trinity. William Whiston, in a letter to William Paul, 30 March 1724, says that

Dr. Clarke has long desisted from putting his name to anything against the church, but privately assists Mr. Jackson; yet does he hinder his speaking his mind so freely, as he would otherwise be disposed to do.

Almost simultaneously with his first defence of Clarke, Jackson advocated Benjamin Hoadly's views on church government in his Grounds of Civil and Ecclesiastical Government, 1714; 2nd edit. 1718. In 1716 he corresponded with Clarke and Whiston on the subject of baptism, defending infant baptism against Whiston; his Memoirs contained a previously unpublished reply to the anti-baptismal argument of Thomas Emlyn.[2]

Jackson was a prolific writer of treatises and pamphlets, many of them against the deists. Jackson's later years were spent in the compilation of his Chronological Antiquities (1752). He published also:

- An Examination of Mr. Nye's Explication … of the Divine Unity, &c., 1715.

- A Collection of Queries, wherein the most material objections … against Dr. Clarke … are … answered, &c., 1716.

- A Modest Plea for the … Scriptural Notion of the Trinity, &c., 1719.

- A Reply to Dr. Waterland's Defense, &c., 1722, (by "A Clergyman in the Country").

- The Duty of Subjects towards their Governors, &c., 1723 (sermon, at the camp near Leicester, to Colonel Churchill's dragoons).

- Remarks on Dr. Waterland's Second Defense, &c., 1723, (by "Philalethes Cantabrigiensis").

- Further Remarks on Dr. Waterland's Further Vindication of Christ's Divinity, &c., 1724, (same pseudonym).

- A True Narrative of the Controversy concerning the … Trinity, &c., 1725.

- A Defense of Humane Liberty, &c., 1725; 2nd edit. 1730.

- The Duty of a Christian … Exposition of the Lord's Prayer, &c., 1728.

- Novatiani Presbyteri Romani Opera, &c., 1728, (this was criticised by Nathaniel Lardner, Works, 1815, ii. 57 sq., and led to a correspondence with Samuel Crell, the Socinian critic, published in M. Artemonii Defensio Emendationum in Novatiano, &c., 1729).

- A Vindication of Humane Liberty, &c., 1730; also issued as second part of 2nd edit. of A Defense (against Anthony Collins).

- A Plea for Humane Reason, &c., 1730, (addressed to Edmund Gibson, then bishop of London).

- Calumny no Conviction, &c., 1731.

- A Defense of the Plea for Humane Reason, &c., 1731.

- Some Reflexions on Prescience, &c., 1731.

- Remarks on … "Christianity as old as the Creation," &c., 1731; continuation, 1733 (by "A Priest of the University of Cambridge").

- Memoirs of … Waterland, being a Summary View of the Trinitarian Controversy for 20 years, between the Doctor and a Clergyman in the Country, &c., 1731.

- The Second Part of the Plea for Humane Reason, &c., 1732.

- The Existence and Unity of God, &c., 1734 (defence of Clarke's proof).

- Christian Liberty asserted, &c., 1734.

- A Defense of … "The Existence and Unity," &c., 1735, (against William Law).

- A Dissertation on Matter and Spirit, &c., 1735, (against Andrew Baxter).

- Athanasian Forgeries … chiefly out of Mr. Whiston's Writings, &c., 1736, (by "A Lover of Truth and of True Religion"; ascribed to Jackson, but not definitely his).

- A Narrative of … the Rev. Mr. Jackson being refused the Sacrament, &c., 1736.

- Several Letters … by W. Dudgeon … with Mr. Jackson's Answers, &c., 1737. Correspondence with William Dudgeon.

- Some Additional Letters, &c., 1737.

- A Confutation of … Mr. Moore, &c., 1738.

- The Belief of a Future State proved to be a Fundamental Article of the Religion of the Hebrews, and held by the Philosophers, 1745, (against William Warburton).

- A Defense of … "The Belief of a Future State," &c., 1746.

- A Farther Defense, &c., 1747.

- A Critical Inquiry into the Opinions … of the Ancient Philosophers concerning … the Soul, 1748.

- A Treatise on the Improvements … in the Art of Criticism, &c., 1748, (by "Philocriticus Cantabrigiensis").

- A Defense of … "A Treatise," &c. [1748].

- Remarks on Dr. Middleton's Free Enquiry, &c., 1749.

- Chronological Antiquities … of the most Ancient Kingdoms, from the Creation of the World for the space of 5,000 years, 1752, 3 vols. (This work was translated into German.) [2]

The most notable replies to Jackson's polemical tracts are by Daniel Waterland.

References

- "Jackson, John (JK702J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Gordon 1892.

- Attribution

![]()