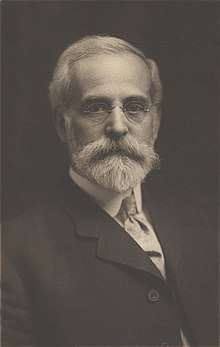

John D. Larkin

John Durrant Larkin (September 29, 1845 - February 15, 1926)[1] was an American business magnate who pioneered the mail-order business model, developed (with business partner and brother-in-law Elbert Hubbard[2]) the marketing strategy of offering premiums to customers,[3] introduced revolutionary employment innovations,[4] and commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright's first major public work, the Larkin Administration Building.[5]

John Durrant Larkin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 29, 1845 |

| Died | February 15, 1926 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Bryant & Stratton College |

| Occupation | Business magnate |

| Known for | Larkin Company |

| Spouse(s) | Hannah Frances Hubbard (married May 10, 1874) |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Levi and Mary Ann Durrant Larkin |

Early life

Larkin was born in Buffalo to parents who emigrated from England to the United States in 1832.[6] He attended public schools in Buffalo during his childhood and began working at the age of 12 at Western Union as a telegraph messenger.[6] In 1862, he began work in the soap manufactory of Justice Weller,[6] his sister Mary's husband. For the next eight years he worked for Weller in Buffalo, learning the business. From courses at Bryant and Stratton he took in 1865, he learned business bookkeeping and when Weller moved to Chicago in 1870, Larkin went with him. He was admitted to the partnership of J. Weller & Co. the next year. While in Chicago, Weller introduced Larkin to Frances Hubbard whom Larkin married in 1874 at her parents' home in Hudson, Illinois.[7]

Larkin Soap Company

In 1875, Larkin sold out his interest in J. Weller & Co. to Mr. Weller, and he and his wife moved to Buffalo. Larkin then set up his factory "J. D. Larkin, Manufacturer of Plain and Fancy Soaps."[6] His only product was a yellow laundry bar named Sweet Home Soap. The business grew and by 1878, the company produced nine different soap products, ranging from "Boraxine" soap powder through a variety of laundry soaps to "Jet" harness soap, "Oatmeal" toilet soap and Glycerine.[7]

Larkin's first salesman was his wife's brother, Elbert Hubbard, who had also been working as a salesman for J. Weller & Co. in Chicago. Hubbard decided to follow his sister and Larkin to Buffalo and work as a salesman. In 1878, Darwin D. Martin was hired as a salesman in Boston. By 1880, as sales to general stores and other merchants who would buy products in large quantities increased, Martin was hired in Buffalo and became the first, and at that time the only, hired office-worker of the Larkin Company as all office work was done by Larkin himself.

While at the Larkin Company, Hubbard pioneered the idea of mail-order merchandising. By offering premiums and bonuses in return for sales, the company was able to dispense with a sales force.[8] By 1902, Larkin needed a building to consolidate offices scattered throughout all of his factories. Martin, who had risen to Treasurer and Corporate Secretary, and William Heath, Larkin's brother-in-law and the head of the Legal Department, suggested Frank Lloyd Wright. Larkin consented and Frank Lloyd Wright received his first commercial commission, the Larkin Administration Building which was completed in 1904 and accommodated 1800 corresponding secretaries, clerks, and executives.[9]

In 1914, the Larkin Company grew so rapidly that the floor space of its offices covered 64 acres.[6]

By 1925, the Larkin Company manufactured most of the 900 catalog items in factories covering sixteen-and-a-half acres on Seneca Street in Buffalo. In addition to their own soaps, cleansers, cosmetics, perfume, pharmaceuticals and food, Larkin offered everything from furniture and clothing to utensils and radios.

Buffalo Pottery

In 1901, Larkin founded Buffalo Pottery to supply the Larkin Company with premiums of china dinnerware for its customers.[10] Completed in 1903, the company's plant was the largest fireproof pottery in the world; and it was also the only pottery in the world completely operated by electricity.[11] In addition to the china produced for distribution as premiums, Buffalo Pottery manufactured many lines of china sold via both retail and wholesale channels and exported its ware to more than 25 countries. The pottery ultimately turned to the production of commercial chinaware. Changing its name to Buffalo China, Inc. in 1956, the company was one of the largest manufacturers of commercial chinaware in the United States.[12] Buffalo China was sold to Oneida Limited in 1983,[13] and went out of operation in 2004.[14]

Legacy

Larkin died in 1926, one of Buffalo's most respected citizens,[15] and is buried at Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo. He was a benefactor of the University of Buffalo, where by 1926, he donated $250,000 (equivalent to $3,610,000 in 2019).[6]

While the Larkin Administration Building was demolished in 1950, a large portion of the original Larkin manufacturing complex survives today including the Larkin Terminal Warehouse which has been converted to corporate offices and houses the headquarters of First Niagara Bank, now home of Key Banks Buffalo division.

See also

References

- Larkin, Daniel Irving (1998). John D. Larkin, a Business Pioneer. Amherst, NY: D.I. Larkin. ISBN 978-0961969714.

- Champney, Freeman (1983). Art & Glory: The Story of Elbert Hubbard. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-295-1.

- Laird, Pamela Walker (2001). Advertising Progress: American Business and the Rise of Consumer Marketing. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801866456.

- Stanger, Howard R. (2000). "From Factory to Family: The Creation of Corporate Culture in the Larkin Company of Buffalo, NY". Harvard Business History Review. 74 (Fall 2000): 407. doi:10.2307/3116433.

- Quinan, Jack (2006). Frank Lloyd Wright's Larkin Building: Myth and Fact. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226699080.

- "JOHN D. LARKIN DEAD". The New York Times. February 16, 1926. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- LaChiusa, Chuck. "John D. Larkin - Biography". buffaloah.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Odell, Digger. "The Larkin Soap Company". bottlebooks.com. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Demolition! The Larkin Administration Building - 680 Seneca Street". WNY Heritage Press. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Altman, Seymour; Altman, Violet (1987). The Book of Buffalo Pottery (2nd ed.). Schiffer Pub. ISBN 0887400884.

- China : It's Origin and Manufacture. Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Pottery. c. 1915.

- Conroy, Barbara J. (1999). Restaurant China : Identification & Value Guide for Restaurant, Airline, Ship & Railroad Dinnerware. Collector Books. ISBN 157432148X.

- "Oneida to Buy Maker of Commercial China". The Wall Street Journal. September 15, 1983.

- "Oneida Completes Sale of Buffalo China Factory; Plant to Operate as Niagara Ceramics Corporation". globenewswire.com.

- Conlin, John. "John D. Larkin". Buffalo Spree. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

External links