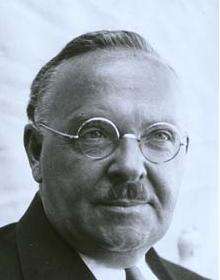

John Andrew Rice

John Andrew Rice Jr. (1888 – 1968) was the founder and first rector of Black Mountain College, located near Asheville, North Carolina. During his time there, he introduced many unique methods of education which had not been implemented in any other experimental institution, attracting many important artists as contributing lecturers and mentors, including John Cage, Robert Creeley, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, and Franz Kline. During World War II, he made it a haven for refugee European artists, including Josef Albers and Anni Albers, who arrived from the Bauhaus in Germany. Later, Black Mountain College became the platform for the work of Buckminster Fuller, who made the college the site of the first geodesic dome. Because of his strong ideas and unusual educational philosophy, Rice became involved in many debates in the socially conservative 1930s, '40s and '50s, becoming known as a very outspoken critic of the standard model of higher education in the United States.

John Andrew Rice | |

|---|---|

John Andrew Rice | |

| Born | John Andrew Rice Jr. 1888 |

| Died | 1968 (aged 79–80) Lanham, Maryland, United States |

| Occupation | Educator |

Early and family life

Rice was the son of Methodist minister John Andrew Rice Sr. and Annabelle Smith, who was from a prominent South Carolina family. He was born at Tanglewood Plantation, near Lynchburg, South Carolina, and attended The Webb School, a highly regarded boarding school located in Bell Buckle, Tennessee, where he met the teacher he would revere all his life, John Webb. Rice then attended Tulane University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree, then won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University.

After graduating from Oxford, he married Nell Aydelotte and began teaching at Webb School, but left after a year to pursue doctoral studies at the University of Chicago, which he never completed. He had three children with Nell Aydelotte before their divorce, of which one son died as an infant and daughter Mary A. R. Marshall and son Frank survived.

Career

Rice secured a faculty position at the University of Nebraska, where he proved himself brilliant in the classroom and in counseling students. His teaching methods were aimed at accelerating the students' emotional and intellectual maturity, rather than encouraging a reliance on a store of subject knowledge.

From the University of Nebraska, Rice took his unique teaching strategies to the New Jersey College for Women. He was forced to resign after two years amid a faculty controversy which was not resolved. He then landed a faculty position at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. At Rollins, he found himself again in a controversial position, as faculty and students found him to be either brilliant and charismatic, or divisive and argumentative. Rice also spoke out against fraternities and sororities and objected to various policies of the president of Rollins, Hamilton Holt, who asked him to resign.[1]

Rice then began planning for the learning community that became Black Mountain College, which opened in 1933 with twenty-one students and three other faculty from Rollins, dismissed for refusing to sign a "loyalty pledge" to Holt. It eventually grew to nearly one hundred. His new ideas included: (1) the centrality of artistic experience to support learning in all disciplines; (2) the value of experiential learning; (3) the practice of democratic shared governance by faculty and students; (4) the value of social and cultural endeavors outside the classroom; and (5) elimination of oversight from outside trustees. He also enjoyed bringing in diverse visitors.

His innovations soon gained the college national recognition. He resigned in 1940 at the request of his faculty, who found his personality polarizing. Financial difficulties led to the school's closure in 1956, though Rice's name lives on in the halls of Black Mountain.

After a divorce from his first wife, Rice married librarian Dikka Moen in 1942 and had two children. He then began another career as a writer, contributing many short stories to such publications as Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post, Harper's and the New Yorker. He also published a book of short stories entitled Local Color (1957), and a classic memoir, I Came Out of the Eighteenth Century (1942), which explains his methods and criticizes grades based on memorization, over-reliance on Great Books and classroom attendance.

Death and legacy

Rice died in Lanham, Maryland in 1968 and is buried at Monocacy Cemetery in Beallsville, Maryland.[2] His daughter Mary A. R. Marshall moved to the Washington D.C. area during World War II, became a leading local opponent of Massive Resistance and represented Arlington, Virginia in the Virginia General Assembly part time for 24 years. His grandson William Craig Rice became Director of the Division of Education Programs of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

References

- "Education: Brilliant Critic". TIME Magazine. November 23, 1942. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- Mononacy Cemetery

- Adamic, Louis. 1936. "Education on a Mountain." Harper's 172:516 - 530.

- Duberman, Martin. 1972. Black Mountain College: An Exploration in Community. New York: Dutton.

- Harris, Mary Emma. 1987. The Arts at Black Mountain College. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Lane, Mervin, ed. 1990. Black Mountain College, Sprouted Seeds: An Anthology of Personal Accounts. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Reynolds, Katherine Chaddock. 1998. Visions and Vanities: John Andrew Rice of Black Mountain College. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- "John A. Rice (1888-1968) - Black Mountain College, Life as a Writer". State University.com, 2008

- "John Andrew Rice: Black Mountain College's Provocative Patriarch". Blackmountaincollege.org.

- Ritholz, Robert E. A. P. 1999. History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1999), pp. 349–350. Blackwell.