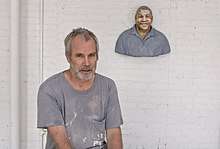

John Ahearn

John Ahearn (born 1952) is an American sculptor. He is best known for the public art and street art he made in South Bronx in the 1980s.

John Ahearn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1952 |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Plaster casts |

Notable work | South Bronx bronzes |

| Movement | |

Life and art

Ahearn grew up in Binghamton, New York, with his twin brother Charlie Ahearn, who is a video artist. John went to Cornell University, but then discovered art. After trying painting, he started making life casts in 1979, while with Colab, a Manhattan artists’ collective. Then he went to South Bronx and worked on the sidewalk in front of Fashion Moda, casting whoever volunteered. He was joined by Rigoberto Torres, who first assisted him and then became his partner.[1] After a decade of intense cooperation, they have been occasionally working together till the present day.[2][3]

In the 1980s, while he was exhibited and appreciated by and participated in art world venues like Brooke Alexander Gallery, Ahearn focused his art and life on The Bronx. He made two copies of every cast - one for himself and the other for the sitter. Between 1981 and 1985, Ahearn, together with Torres, created four sculptural murals for the sides of tenement buildings — We Are Family, Life on Dawson Street, Double Dutch, and Back to School — depicting everyday life in the neighborhood.[4]

His 1991 survey of portraits of ordinary people was called South Bronx Hall of Fame.[5] In 2017, his recent casts were installed on walls on Lower East Side.[6]

The South Bronx bronzes

In 1989, Ahearn received the commission to make sculptures for the 44th Police Precinct in Bronx. He thought of Paseo de la Reforma, but instead of heroes, he decided to immortalize people he knew. Ahearn made bronze statues of three black people from his South Bronx neighborhood: Raymond and his pit bull, Daleesha and her roller skates, and Corey and his boom box and basketball.[1] The statues were installed in 1991.[7]

Faced with protests from black bureaucrats on one hand and black neighbors on the other, who believed that the subjects did not adequately represent the community, Ahearn removed the statues five days after their installation. The South Bronx bronzes inspired Jane Kramer to write a long essay in The New Yorker about Ahearn and others involved in the controversy, about art, race and society,[1] which she expanded into a book, Whose Art Is It?, in 1994.[8] The bronzes now stand in the Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens.[7]

See also

References

- "Whose Art Is It?". The New Yorker. 21 December 1992.

- "An Artistic Partnership Reunites in the Bronx". The New York Times. 14 May 2017.

- "Art and Power". Harvard Political Review. 27 June 2018.

- Kwon, Miwon (2002). One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity. Cambridge (Massachusetts), London: MIT. p. 88. ISBN 0-203-13829-5.

- "Two Generations of South Bronx Artists". The New Yorker. 12 September 2016.

- "Sculptor John Ahearn Brings Iconic New Yorkers To Streets To Meet The Neighbors". The Huffington Post. 20 January 2017.

- "Inside NYC's most explosive public-art controversies". New York Post. 8 November 2017.

- Kramer, Jane (1994). Whose Art Is It?. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822315491.