Johannes Wilde

Johannes Wilde CBE (2 July 1891 – 13 September 1970) was a Hungarian art historian and teacher of art history. He later became an Austrian, and then a British, citizen. He was a noted expert on the drawings of Michelangelo. Wilde was a pioneer of the use of X-rays as a tool for the study of both the creation and the state of conservation of paintings. From 1948 to 1958 he was deputy director of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London.[1][2]

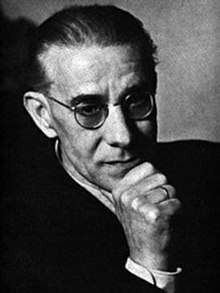

Johannes Wilde | |

|---|---|

Portrait photograph of Johannes Wilde by Ursula Pariser | |

| Born | János Wilde 2 July 1891 Budapest, Hungary |

| Died | 13 September 1970 Dulwich, England |

| Nationality | Hungarian, Austrian, British |

| Occupation | art historian |

| Known for | catalogue of Michelangelo drawings in the National Gallery, London |

Life

Johannes Wilde was born János Wilde on 2 July 1891 in Budapest, Hungary. He was the last of six children of Richard Wilde (died 1912) and his wife Rosa née Somjágy (died 1928). From 1909 to 1914 he studied art, philosophy and archeology at the University of Budapest and then from 1915 to 1917 studied for a doctorate under Max Dvořák at the University of Vienna, defending his thesis summa cum laude in July 1918. He returned to Budapest and was until 1922 an assistant to Simon Meller in the department of prints and drawings of the Museum of Fine Arts.

In the brief period of the Hungarian Soviet Republic of Béla Kun in 1919, Wilde worked with Frederick Antal on the sequestration of privately owned works of art of national significance.

Max Dvořák died in February 1921, and in 1922 Wilde moved permanently to Vienna in order to work with Carl Maria Swoboda on a collected edition of Dvořák's writings. This was published between 1924 and 1929. He became an Austrian citizen in 1928, and on 6 February 1930 married the art historian Julia Gyárfás.[2]

Theatrum Pictorium

From 1923 Wilde worked as an assistant Keeper, and later as a Keeper, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, where he worked principally on Italian Renaissance paintings. Many of the paintings in the collections of the museum were in a poor state of conservation in the Hofburg.[3] He carefully researched and catalogued the Italian paintings, many of which were documented in David Teniers the Younger's Theatrum Pictorium, though with incorrect attributions.

It was Wilde who discovered that the hitherto separate paintings by Antonello da Messina in the collection "St. Nicolas and a Female Saint" (attributed by Teniers to Bellini), "The Virgin and Child Enthroned", and "St. Dominic and St. Ursula", were all fragments of one altarpiece and he oversaw the reconconstruction of the San Cassiano Altarpiece in 1928.[4]

X-rays

By about 1928 Wilde and the restorer Sebastian Isepp were using X-radiation as a systematic aid to understanding both the physical condition of paintings and the artistic processes by which those paintings had been created. At first they made use of the facilities of the Röntgenologisches Institut of Vienna University, but in 1930 an X-ray laboratory was installed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. While Wilde was not the first to use X-rays to examine pictures, this was the first such laboratory in Europe. He first published his findings on The Gypsy Madonna and The Three Philosophers'[3] In the next eight years Wilde made more than 1000 X-ray photographs of works in the museum. He also maintained a steady flow of scholarly publications.[3]

Britain

After the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria into the German Third Reich on 12 March 1938, Wilde's Hungarian Jewish wife Julia was at risk. With the help of friends including Count Antoine Seilern, the couple left Vienna for the Netherlands in April 1939 to visit an art exhibition; from there they flew to England, where they stayed at the home of Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery and Surveyor of the King's Pictures.

Wilde soon went to Aberystwyth to work on Seilern's pictures, which had been sent to the National Library of Wales for safety at the beginning of the Second World War. He also worked on the pictures of the National Gallery, which were in the same building. The British Museum collection of Italian drawings was also housed there and, through Arthur Ewart Popham, Wilde was asked in June 1940 by the Trustees of the museum to start work on cataloguing them too.[2]

In the same year, in what Kenneth Clark describes as a "revolting incident", Wilde was charged with signalling to enemy submarines, interned in a concentration camp, and deported to another camp in Canada, where he barely survived.[2][5]

Publications

The publications of Johannes Wilde include:

- Max Dvořák; Carl Maria Swoboda and Johannes Wilde (eds.), Kunstgeschichte als Geistesgeschichte. Studien zur abendländischen Kunstentwicklung. München: R. Piper, 1924

- ——— , Das Rätsel der Kunst der Brüder van Eyck: mit einem Anhang über die Anfänge der holländischen Malerei. München: R. Piper, 1925

- ——— , Geschichte der italienischen Kunst im Zeitalter der Renaissance akademische Vorlesungen (2 volumes). München: R. Piper, 1927–28

- ——— , Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kunstgeschichte. München: R. Piper, 1929

- Arthur Ewart Popham and Johannes Wilde, The Italian Drawings of the XV and XVI Centuries ... at Windsor Castle. (catalogue, with reproductions; the sections relating to Michelangelo and his school by J. Wilde, translated by J. Leveen) London: Phaidon Press, 1949

- Johannes Wilde, Italian drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: Michelangelo and his studio. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1953

- ——— and Arthur Ewart Popham, Italian drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum: Artists working in Parma in the sixteenth century; Correggio, Anselmi, Rondani, Gatti, Gambara, Orsi, Parmigianino, Bedoli, Bertoja. London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1967

- ——— Venetian art from Bellini to Titian. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974. ISBN 019817327X (posthumous publication)

- ——— ; John Shearman and Michael Hirst (eds.), Michelangelo: six lectures. Oxford studies in the history of art and architecture. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 9780198173168 (posthumous publication)

References

- Julie Tancell (2000). Wilde, Johannes (1891-1970): Identity statement. Courtauld Institute of Art. Accessed May 2013.

- Dennis Farr, "Wilde, Johannes (1891–1970)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, Jan 2011. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36895.

- Michael Hirst (March 1971). "Obituary: Johannes Wilde". The Burlington Magazine, 113, 816: 155-157 (subscription required)

- J. Wilde, "Pala di San Cassiano" Rekonstruktionsversuch, Jahrbuch der Kunsthist. Samml. in Wien, n. s., III (1929), pp. 57-72

- Kenneth Clark (June 1961). "Johannes Wilde". The Burlington Magazine, Special Issue in Honour of Professor Johannes Wilde. 103, 699: 205 (subscription required)