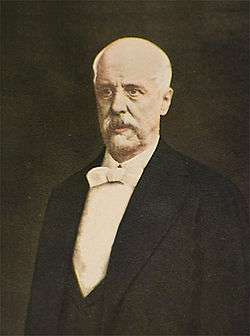

Joaquín García Icazbalceta

Joaquín García Icazbalceta (August 21, 1824 – November 26, 1894) was a Mexican philologist and historian. He edited writings by Mexican writers who preceded him, wrote a biography of Juan de Zumárraga, and translated William H. Prescott's Conquest of Mexico. His works on Colonial Mexico continue to be cited today.

Life

García Icazbalceta was born in Mexico City to a wealthy Spanish family. The family was exiled to Spain in 1825, shortly after the recognition of Mexican independence, by an act of Congress, and was not able to return until seven years later.

He was educated by tutors and through independent reading. He learned several Continental languages and delved into the study of Iberoamerica. His studies were interrupted by the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, in which he took part. After the war he returned to scholarly pursuits.

He married Filomena Pimentel (who died in childbirth), granddaughter of Count of Heras.

He spent the better part of his life amassing a large collection of books, documents, and manuscripts from the colonial era, which he used in his work.

Work

García Icazbalceta wrote his biography of Juan de Zumárraga, the first Archbishop of Mexico, during a time when Mexican history was being reevaluated, resulting in criticism of the Archbishop and the mendicant orders who converted the natives. In it, he countered Liberal and Protestant charges that the Archbishop was "ignorant and fanatical" by casting him and other Franciscans in the role of the saviors of the Indians, from the brutality of the civil authority.

He also highlighted the Archbishop's role in fostering early educational institutions such as the Colegio Santa Cruz and credits him with bringing the first printing press to the Western hemisphere.

He especially objected to charges—levelled by Mier, Bustamante, and Prescott—that Zumárraga had played any role in the destruction of native Aztec codices, arguing that most of the destruction had occurred before Zumárraga's arrival, that no Spanish chroniclers mention any book burnings, and that the one mentioned by Alva de Ixtlilxochitl was committed by Tlaxcalans in 1520.

He also used the book to criticize the hypocrisy he viewed in Liberal legislators, who, while attacking the Archbishop for cruelty to the Indians, betrayed the indigenous heritage of the nation by lifting limitations on the export of ancient works of art and artifacts.

The book was sufficient to restore the credibility of the Archbishop and the place of the Franciscans as founders of the Mexican society in the Mexican consciousness, but it raised other questions. Many people were uncomfortable with the lack of any mention of the apparition of the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of Guadalupe or Zumárraga's construction of a chapel in her honor.

In fact, García Icazbalceta had written a chapter on the subject, which he elected not to include in the final draft at the behest of Francisco Paula de Verea, bishop of Puebla. In it, he divulged that he had not found any contemporary documents referring to the apparition, identifying Miguel Sánchez's 1648 Imagen de la Virgen as the first to appear.

Despite his prestige as Mexico's pre-eminent historian of the time, his political conservatism and his devout Catholicism, attacks were made against his reputation by defenders of the historicity of the apparition. In response to a demand made by Pelagio Antonio de Labastida, Archbishop of Mexico, he wrote a detailed account of "what history tells us about the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego".

In it, he detailed all of the historical problems with the traditional legend of the apparition. These included the silence of historical documents on the phenomenon, especially that of Zumárraga, the lack of any of the Nahuatl documents mentioned by previous historians, the unremarkability of the blossoming of flowers during the month of December (an important aspect of the traditional narrative), and the improbability that "Guadalupe" was a Nahuatl name. He further cited inconsistencies between the studies of the icon as reasons to doubt the apparition's historicity.

He started work on a dictionary of Mexican Spanish, Vocabulario de Mexicanismos, which was only finished up to the letter "G" and was published posthumously.

Icazbalceta was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1881.[1]

Death and legacy

García Icazbalceta died of "cerebral apoplexy" at the age of 70. His writings on the work of the Franciscan Order in Colonial Mexico influenced the work of Ignacio Manuel Altamirano, a contemporary historian.

Bibliography

- Apuntes para un catálogo de escritores en lenguas indígenas de América. México, 1866.

- Don fray Juan de Zumárraga, primer obispo y arzobispo de México. (Rafael Aguayo Spencer y Antonio Castro Leal, editors). Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1947 (originally published 1881).

- Investigación histórica y documental sobre la aparición de la virgen de Guadalupe de México (with Alonso de Montúfar and Primo Feliciano Velázquez). México: Ediciones Fuente Cultural : distribuidores exclusivos Librería Navarro, 1952.

- Carlos María de Bustamante (colaborador de la independencia). México: Talleres tipográficos de el Nacional, 1948.

- Indice alfabético de la Bibliografía mexicana del siglo XVI. México: Porrúa, 1938.

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joaquín García Icazbalceta. |